TREE LIFE

June 2022

502

Yellowstone National Park Photo by Rob Jarvis

Welcome to this Tree Life 502! We are in the middle of a bucket-list trip to the Western United States where we are visiting one of our daughters and her husband and their family and have been fortunate enough to visit some of the most special places where there are not only the largest living things in the world, Giant Sequoias, some of the largest Redwoods, but also the oldest living trees on the Planet Earth, the Bristle-cone pines. When you add to this the other-worldly sights around the geo-thermal geysers, mud-holes and hot springs of Yellowstone National Park as seen above, it really has been a trip of a lifetime. Apologies if you only like Zimbabwean trees, or think that this Newsletter should only be about our trees, however I guess not many will have the chance we have just had to tick these boxes and if you do get the chance, well then snatch the opportunity with both hands and swing through these trees. If you don’t, well then enjoy our journey!

And don’t forget to come to our AGM/Social on the 26th June at 3A Rockyvale Close, we look forward to meeting up there!

Cheers!

Tree Outing to National Botanical Garden, May 2022

By Tony Alegria

The regular Saturday morning monthly tree outing took place on the 7th May and there were just seven of us to enjoy a bright sunny day botanising. We began by looking at the trees right in front of where we normally park. There we found another two Ormocarpum growing side by side fairly close to the Ormocarpum zambesianum, Zambezi caterpillar-pod. One of these trees had flowered but unfortunately the flowers were too high up for us to identify the species. Knowing that Tom Muller often planted three or four trees of the same species near each other, these trees were most likely the Ormocarpum zambesianum. And right next to these trees was a huge Bauhinia petersiana with a trunk diameter of some 30 cm. Growing in this area was a Commiphora which we deduced was a C. karibensis.

We also looked at a Berchemia discolor, bird plum which still had some fruit, the fruit is relished by people as well as birds. After having a look at another Berchemia discolor, we moved on to the “corner” where Pterocarpus lucens had a few fruit – a seed within a wing. Nearby there was a tree labelled Ziziphus abyssinica but we are not sure it is actually one of them and this tree was laden with fruit like I have never seen before. After having looked at some Commiphora caerulea and the Schinziophyton rautaneni , Manketti-tree, we tried some remote botanising. Across the road in the golf course are a few trees we tried to identify – we saw Julbernardia globiflora, Toona ciliata, Combretum molle, Acacia sieberiana, Brachystegia spiciformis and a tree which had longish looking elliptical leaves. Through binoculars, the trunk could be seen and it looked like a pink jacaranda, Stereospermum kunthianum. We then compared the pink jacaranda in the golf course with those in the Botanical Garden – positive Id!

Radermachera sinica flowers Photo by Tony Alegria

The huge Ceiba pentandra had fruit and there was a lot of “Cotton wool” around. Nearby was one of the two species of trees we saw in flower that morning. There were two trees, the one had a single flower but the other had loads of flowers – long tubular white flowers on a Chinese tree – Radermachera sinica. Not too far from these trees is a Colvillea racemosa. Colville’s Glory from Madagascar with loads of buds – this tree is really spectacular when in flower.

Homalium abdessammadii flowers Photo by Tony Alegria

Some of the other trees we looked at but are not mentioned above:

What looked like an Albizia adianthifolia, Albizia glaberrima, Albizia gummifera and Albizia schimperiana.

Delonix adansonioides, Polyscias fulva, Cordia africana, Rauvolfia caffra, Ficus capreifolia and Homalium abdessammadii.

Sarcodes sanguinea flowers Photo by Rob Jarvis

Fantastic fact In the Sequoia forests in Yosemite a feature at this time of year are the snowplants that send up an inflorescense from the forest floor. These are plants that have no photosynthetic ability and actually parasitise the fungi growing on and around the roots of the sequoias, redwoods and pines that populate the forests of Oregon, Nevada and California. They are known as Sarcodes sanguinea and they emerge as the snow melts away. As you all know the Latin name translates to “bloody flesh-like thing” so its common name is a much gentler appellation. An indirect parasite of conifers that feeds off mycorrhizal fungi and is a mycotrophic plant.

Outing to Darwendale (Manyame) Dam on 15 May 2022

By Jan van Bel

On Sunday 15th May we had an outing that took us a little further than the usual tree-walks in and around Harare. The venue was Mbiti Lodge at Darwendale Dam (Lake Manyame). Mbiti, Shona name for otter, clearly alluding to the wild life around the lake which is visible from the lodge.

We arrived there after driving for more than an hour. The last 10 km over a good dust road. We arrived at the bush camp which is an oasis of clean green lawn and trees of all ages. We were welcomed by Derek and Anthea Bruk-Jackson with a warm morning drink and snack. The place is used to receiving groups of people and has a nice sitting area with enough seats for our group of about 15 people. The shade was provided by an old Ziziphus mucronata, buffalo-thorn, with around it a nice variety of different young and old trees. The owners wanted to have the trees identified and with the help of Tony we started to look at all those familiar trees which names that are reluctantly trying to emerge from the deep fog of our brains.

Gymnosporia senegalensis, confetti tree and Pavetta schumanniana, poison bride’s bush, were quite impressive by their unusual big size. Remarkably this place had plenty of those large leaved pavettas, some still in flower. Around the sitting area was a sizable Piliostigma thonningii, monkeybread. Some still see it as a bauhinia, which was its old name. Also a Grewia monticola. false brandybush, judging from the very dark dull green of the leaves upper side, stood guard. The underside silvery-white, making the discolor contrast with the upper side even more outstanding. Senna singueana, winter senna, and Parinari curatellifolia, mobola plum, were well represented all over the place.

Ficus sur at Mbiti Lodge Photo by Rob Jarvis

A big Albizia amara, bitter Albizia, Combretum molle, velvet-leaved combretum, Pterocarpus rotundifolius, round-leaved bloodwood, and Ozoroa reticulata, currant raisin tree all close together and growing very high searching for the sun. We saw a few Ehretia amoena, stamperwood, Clerodendrum eriophyllum, White cat’s whiskers, and Searsia longipes, large-leaved rhus, a few Ficus sycomorus and one other type of ficus which could have been Ficus natalensis but no one to confirm. 1 or 2 Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia, kudu-berry and a rare Securidaca longepedunculata, Violet tree . Also only one Cassia abbreviata, shambok pod. Antidesma venosum, tassel-berry was abundant and frequently seen.

It was evident that many trees were planted considering the age and variety. Some must have been there long ago like the Pappea capensis, indaba tree, a huge tree hovering over some smaller planted trees. We had to send one of the workers to climb into it to pick a leaf for identification. A few Philenoptera violacea. Rraintree; few Faidherbia albida. Apple-ring thorn tre ; even Monotes glaber and M. engleri, the pale and the pink-fruited monotes, seem to have been planted there. Other trees evidently not being at home here were Enterolobium contortisiliquum. Earpod tree, but also Khaya anthotheca. Red mahogany; Cordyla Africana. Wild plum, must have been introduced. Planting still going on as evidenced by some small trees less than half a meter high like a tamarind, pod mahogany and nyala berry.

The list goes on here: Protea gaguedi. African protea; Diospyros lycioides. Red star-apple; Pterocarpus angolensis. Mukwa; Combretum imberbe. Leadwood, was easier to identify with its spines and smaller leaves. Another Combretum with large leaves was more difficult to name and just got the sp. after its name. Sterculia africana and Bridelia micrantha must have been introduced here and only one specimen of each was seen.

Before we were leaving our host wanted to have one more tree identified that was standing a little apart. It had only one beautiful yellow flower. We hadn’t yet encountered one of these, easy to identify as Gardenia volkensii. Common gardenia. A refreshing drink was offered us in a thatched enclosure with bar counter made of an old polished tree-trunk, before we drove back home.

Additional Note by Tony Alegria

Pressed leaves of Gmelina arborea Photo by Tony Alegria

On arrival, at Mbiti, we found that letters of the alphabet had been stamped on square metal discs to label the trees. Well, we had to have numbers stamped on the spare discs as we identified about forty-five trees that were big enough to take a nail, smaller trees such as the Flueggea virosa and Pavettas were not labelled. Samples of some trees were taken for later identification. On arrival at home, I pressed the leaves for later identification by Mark Hyde. The Terminalia mollis was confirmed. There was a tree next to the car park with large leaves which I thought could be a Gmelina arborea, this was also confirmed by Mark. There was a rather large combretum and a few smaller ones that resembled the river bushwillow but could not be identified – it turned out to be a Combretum apiculatum, red bushwillow.

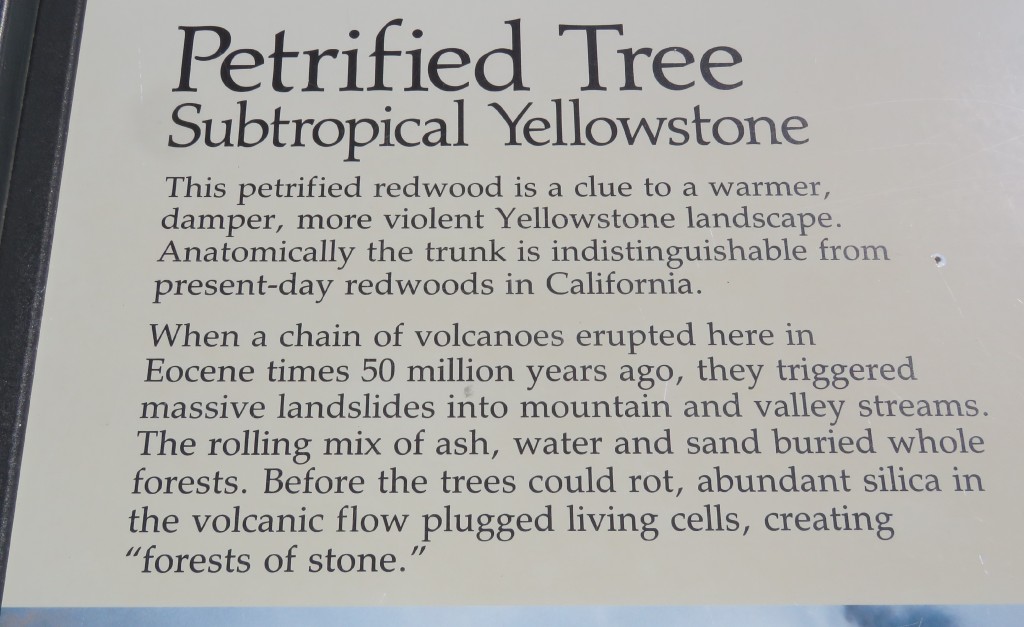

Petrified Forest

By Rob Jarvis

Petrified Tree Photos by Rob Jarvis

The text below indicates just how this fossilised tree was formed and the most amazing thing about the story is that to all intents and purposes, so far as scientists can determine, the tree was very similar to the Redwoods of California as they are today, some fifty million years later, virtually unchanged. Of course in our neck of the woods we almost never see petrified trees still standing, but here in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, just below the border with Montana, there is a huge specimen still upright some fifty million years later. At various places in and around the tourist destinations we visited, some huge petrified logs were on sale and ranged from a few hundred dollars to close to US$6 000 each for some choice specimens about a metre and half long with a girth of close to a metre. Where this tree on the left still stands there once were three similar upright stems, but two were broken up and taken away by souvenir hunters. The nearby hillside, which unfortunately we did not have time to visit, the Parks staff have uncovered at least 16 other trees and these can easily be seen by taking a short hike.

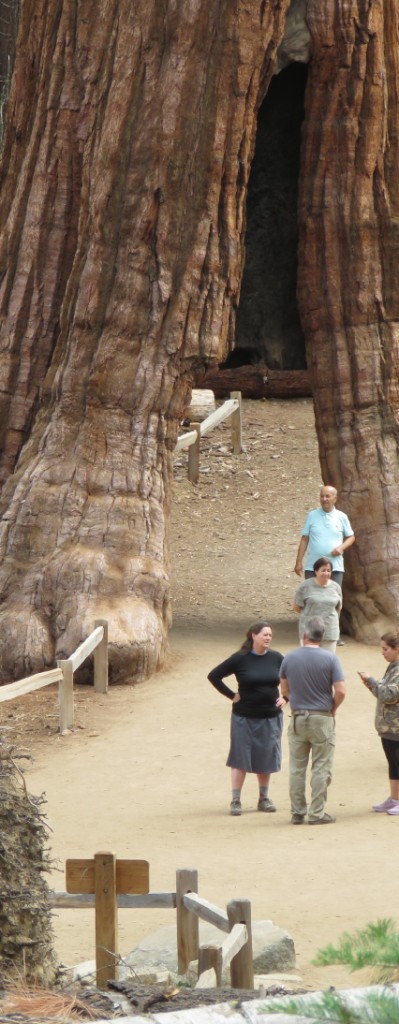

The Giant Sequoias of Mariposa Grove, Yosemite

By Rob Jarvis

Grizzly Giant Photo by Rob Jarvis

You have no choice but to walk in peaceful silence through the various copses of giant sequoias that make up one of only three colonies of these magnificent trees that occur in the Yosemite National Park. The one we went to is called Mariposa Grove and there are approximately 500 mature trees thereabouts. One thing that immediately strikes visitors to these magnificent parks is just how frail the trees are in reality. Strangely enough although fire is a huge threat to very largest trees, fire in fact allows the Sequoias to thrive with older generation individuals in the forest often falling and being consumed by fire and that triggers the germination of new trees and allows them to flourish in the space thus created. The trees are surprisingly poorly-rooted with no sign of a tap root and upended trees literally just have a shallow root ball about 2 or 3 times wider than the diameter of the stem. Given the size of the trees, these are huge and the picture below shows just how big they can be. On the left we see a tree that had been cut at ground level, initially to allow horse and carriages to pass through and later motor-vehicles, but now the Park authorities have closed off vehicular access and tiny humans pass through the covered bridge of overhead wood. The Giant Sequoia is known by botanists as Sequoiadendron giganteus and the Grizzly Giant in this grove is the second largest tree known and is probably over 2 000 and maybe close to 3 000 years old. Venerable indeed.

Charcoaled giant Photo by Rob Jarvis

Sequoias have a spongy outer bark which somewhat protects them from fire and other damage and allows a measure of recovery. Fire in recent years has wreaked havoc and all over this grove you can see remnants of once huge trees standing stark and blackened and in many cases charcoaled giants lying along the ground. Giant sequoia wood is relatively useless as timber unfortunately, unlike the Coastal Redwoods mentioned elsewhere in this newsletter. So when they die and fall they slowly crumble and rot away until nothing is left. There are many spots on the trails where the Park authorities have outlined in the ground the outer perimeter of long-disappeared giants. Nevertheless it is still an amazingly cathedral-like place to walk through, observing the absolute enormity of each tree still standing and the length and straightness of those either reaching for the skies above or crossing canyons, rivers and streams along the way if they have taken a tumble.

Sequoias are big Photo by Rob Jarvis

Other conifers populate the hills and valleys but their size pales into insignificance when compared with the sequoias

Notice of the 72nd AGM

AGM venue Photo by Rob Jarvis

The Annual General Meeting of the Tree Society of Zimbabwe will be held at 3A Rockyvale Close, Chisipite, Harare on Sunday 26th June 2022 at 9.30 am

Any proposals/resolutions and nominations for office bearers (and any volunteers to be on the Committee) should be forwarded by email to the Secretary Teig Howson at: teig.howson@gmail.com by Thursday 23rd June if possible, although proposals and nominations will be accepted from the floor. Venue details and directions to follow. N.B. The minutes of the 71sth AGM held last year will be circulated again by email and thus will be taken as read at this years’ AGM. You need to be paid up to vote – Pay your subscriptions in US$ at the AGM.

AGENDA

- Notice convening the meeting. 5. Treasurer’s Report

- Apologies 6. Election of Office Bearers

- Matters Arising 7. Any other business

- Chairman’s Report

However, as we have done in the recent past, we will be having the social on the same day, program below:

09: 30 Coffee / Tea and Eats 12:00 Socializing and lunch

10:30 AGM 14:00 Fun Quiz

11:00 Scavenger Hunt 15:00 Coffee / Tea / Eats and socializing

This social will be different! Lunch will consist of a Potjie and sides kindly organized by Rob Jarvis. Details to follow. Bring your own chair and drinks.

Plates and cutlery provided. Big Prizes in the Quiz and Scavenger Hunt!!!!

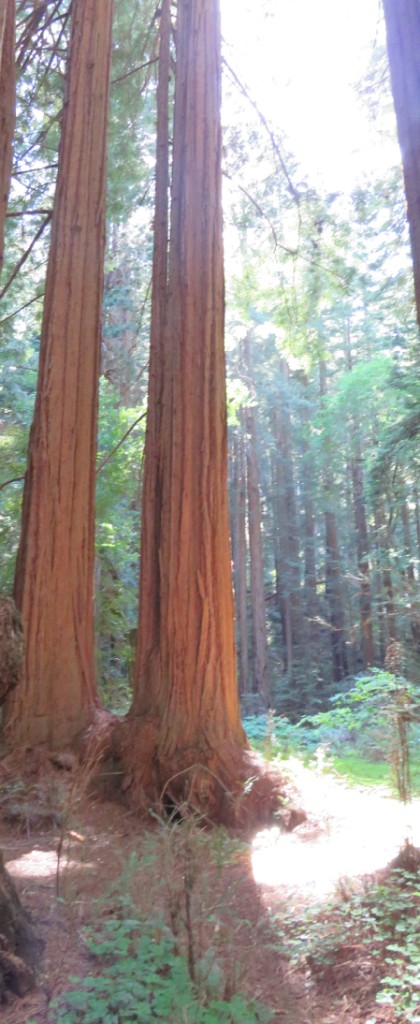

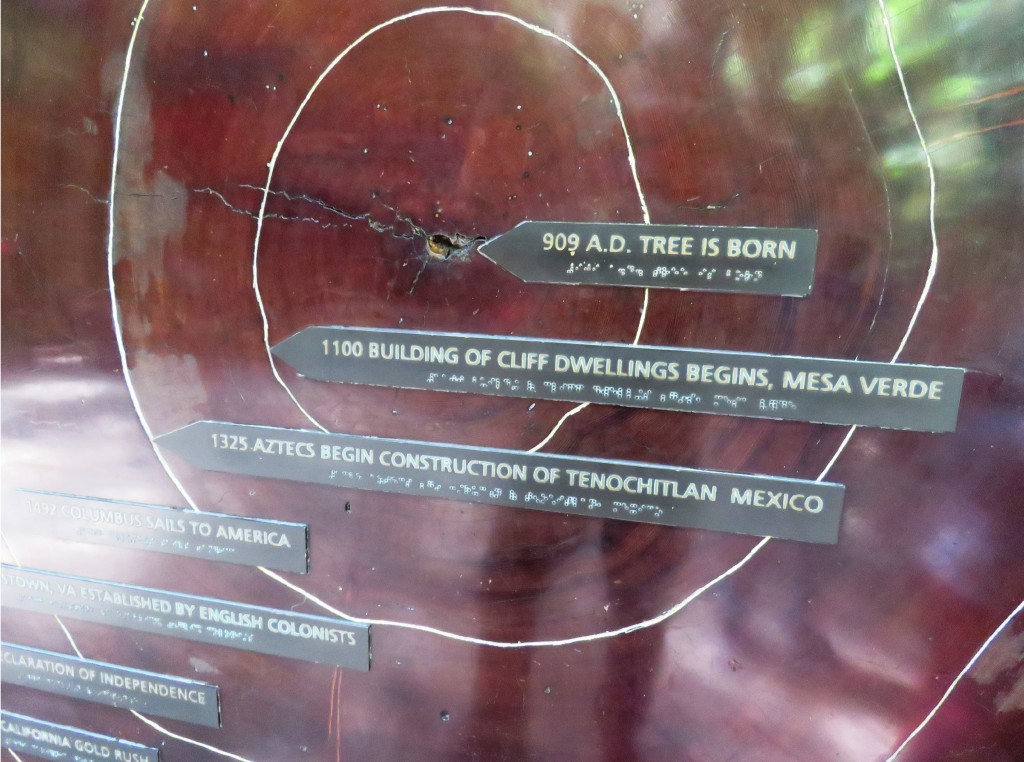

The Coastal Redwoods of Muir Woods National Monument

By Rob Jarvis

Sequoia sempervirens Photo by Rob Jarvis

A day or two after arriving in San Francisco and attending our daughter Emma’s graduation, we crossed the famous Golden Gate Bridge, we ventured into the Muir Woods Park with spouse Leif and his parents Saxon and Wendy Sigerson. When you park at the excellent facilities where like all parks in the United States, there is invariably incredibly well-presented displays telling you all about the Park, the trees and the history of the place. However you have no idea what you are about to see until you head a little distance up the trail along and crystal clear stream alongside the path. Suddenly you turn a corner and there they are, tree after tree of “old growth coast redwoods” Sequoia sempervirens. The trees speak for themselves, they are huge! Towering way above our crick-in-the-neck angle, you have to stand some distance away to appreciate them in their magnificence. And for them to still be preserved as they were before the 1848 Gold Rush, so close to a major world-class city like San Francisco. Below you see a burl on the stem of a pathside tree.

Burl on redwood Photo by Rob Jarvis

Sequoias live a long time Photo by Rob Jarvis

One huge specimen has been cross-cut and preserved in the car park area with the white lines seen above depicting the growth rings that coincided with major historical events during the lifetime of the tree whilst it was still standing. This particular one was only 1 100 years old or so before it fell to the wood cutter’s axe!

The Park Service is making strenuous efforts to re-establish the health and vitality of the forests and attending to details like the under storey plants that occur in these forests, removing alien invasives and allowing the natural wildlife to proliferate.

Long may future generations of Americans and lucky visitors like ourselves have the opportunity to walk in the shade of these giants. The waters of the stream are crystal-clear, there is almost no trash thrown idly into the brush on either side of the paths and people are very careful not to step outside designated walkways.

Next time we would like to return and spend some more time in this Park and walk to its farthest, most hidden corners.

Bristle-Cone Pines Photo by Rob Jarvis

The Bristle-Cone Pines of Inyo Forest Reserve

By Rob Jarvis

There is a town called Bishop that you sometimes stay at and definitely pass through on the way up from Death Valley to Yosemite. We had some car problems so we definitely had to stay there and we took a short-hire car from a local dealer and went up the nearby White Mountains into the Inyo Forest Reserve. The Inyo forest is a bit of a misnomer because for countless kilometres you drive through country labelled as part of this Park but there is hardly a tree in sight.

Then you go up into the mountains and right up there, near the top, we were suddenly in amongst them, bigger than we envisioned they were gnarled, twisted and clearly ancient. They only grow on the dolomitic rocky areas and on North facing slopes they grow well, but on south facing slopes they edge their way slowly and inexorably to posterity. The oldest measured so far, by counting growth rings is 5 000 years!

“Bobby-socks effect” on Yellowstone trees Photo by Rob Jarvis

In the geothermal areas epitomised by a large part of the Yellowstone National Park one of the big issues is the ever changing landscapes around the geothermal springs, geysers and the like. So when a new hot spring finds its way to the surface the damage the flooding of new ground does to the already growing trees, is dramatic and immediate. It is called the “bobby-socks effect” as the highly sodic and extremely hot water destroys the standing trees, burning their lower boles a blinding white colour. The effect somewhat resembles our own trees in Kariba, left standing but dead, by the rising flood waters as the lake rose and filled.

Anyway there you are folks a little bit of Zimbabwean tree botanising and something about the great forests of North America. Much as we do not like the conifers in our own sub-tropical environment, they certainly have their place in habitat over vast swathes of North America.

Long may it remain so.