TREE LIFE

July 1987

MASHONALAND CLENDAR

Saturday July 4th : Botanic Garden Walk. More about Jesse bush. Meet at car park at 1045 hours for 1100 hours.

Sunday July 19th : Lindhurst Farm, the home of Erica Boshoff and family. Lindhurst is just outside the city and has some excellent miombo woodland on the banks of the Ruwa River. This woodland has been carefully protected by the family although pressure for firewood is increasing greatly. There is also “refuge walling” along the river, built by the Shona as protection from the Ndebele. We will use our own cars so please arrange lifts. Meet at the farmhouse at 0930hours for tea.

Sunday August 2nd : ALOE RALLY TO THE GREAT DYKE AND MUTOROSHANGA COUNTRY CLUB

The Aloe Society invites members of the Tree Society to join in the popular “Fun” Rally to be run this year through the Great Dyke and lunching at the attractive Mutoroshanga Country Club. The ladies of the Club have kindly offered to provide lunches at $5 and teas at $1, and your lunch time ‘G&T’ can be purchased from the bar. The Dyke Aloe (Ortholopha) should be in all its glory and the weather superb, so ‘team up’ with friends and come along. Two to a team, questions of a general nature and all that is required is reasonable powers of observation and deduction. If interested please telephone Mienkie Weeks on 50055 any time or Vida Siebert on 303836, evenings, before the 18th July to enable us to advise numbers for lunches. Further details will appear in next Tree Life.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

On Sunday June 7th we spent a very pleasant day in the Matopos, in the “Honey guide Highway” area, and along the road. This area includes some of the few Msasa patches in the Matopos and was quite varied. Near the Circular Drive End we found all very dry with some loss of trees. One wonders how well Msasa can stand drought conditions. We feel that there will be more dead trees there. At the Msiteli Valley end of the Road, the msasa were more advanced and some young leaf looked more hopeful. In all we identified some 80 species along the road and in the Msasa beyond.

Albizia versicolor. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

The only Acacia seen was Acacia sieberana, relatively large numbers of Aloe Excelsa, a lot of Artabotrys brachypetalus, one in particular, a medium sized tree, fallen but shooting again, all with many fruit like galls, a large Albizia versicolor, which puzzled us a while, until we found the dry curled up pods. Further on were some tall Albizia tanganyicensis, Brachylaena huillensis, many Brachylaena rotundata. Brachystegia spiciformis, were of course prominent, right through the road background, some very long pod Cassia abbreviata, Commiphora marlothii plentiful on the rocky heights, Cordia grandicalyx, Cussonia arborea, not so common here, Dovyalis zeyheri, almost thornless, Entandophragma caudatum, with many wooden bananas hanging, high up on the rocks some very straight boled Erythrina latissima, plenty Euclea natalensis, some few Euclea racemosa subsp. schimperi, so shiny in contrast one sole Euclea divinorum, several Euhorbia cooperi, and fewer E.ingens, 5 figs Ficus glumosa, Ficus ingens, usefully compared with F.salicifolia, Ficus sur, Ficus thonningii, Hexalobus monopetalus, baboons breakfast, many Lavender trees, Heteropyxis dehniae, Homalium dentatum, right alongside Strychnos usambarensis both not often seen by us, Maerua juncea, in among the Msasa, Maytenus senegalensis. Flowering many dry Mundulea sericea, Ochna pulchra, Ochna schweinfurthiana, Pavetta eylesii with bark stripping, Ptaeroxylon obliquum, sneezewood, many Pterocarpus rotundifolius, much fewer Mukwa, Pterocarpus angolensis, Pterolobium stellatum, with savage thorns, many Rhus leptodictya some Rhus tenuinervis, some Rhus pyroides, Sclerocarya birrea with fruit, a very corky Strychnos coculoides, many Strychnos madagascariensis, Tarenna neurophylla and what we thought Teclea trichocarpa, which apparently occurs here in spite of Palgrave’s map Turraea fischeri confined to the Matopos, Vernonia amygdalina in full flower, white and lilac.

-C.Sykes

NEW COMMITTEE

Last month’s Tree Life omitted to announce the composition of the new Committee elected at the AGM on 17th May, 1987. For your information here it is :

Chairman Dick Hicks

Vice Chairman Meg Coates Palgrave

Treasurer Joy Killian

Secretary Sheila Weaver

Membership Secretary Vida Siebert

Committee members Georgie Granelli, Molly Kilpert, Maureen Silva Jones, Maureen Lumholst Smith

Richard Mithen, Philip Haxen

SUBSCRIPTION REMINDER :

Have you paid your subscription, due on 1st April, please? According to the Constitution any member whose subscription is in arrears for more than three months shall cease to be a member so let us have your payment soon.

BOTANICAL GUIDES TO THE ALLUVIAL SANDS AT MANA, THE CIRCULAR DRIVE AROUND LONG POOL

This guide to Mana is the first that Meg and I prepared while guests of the Zambezi Society at a most informative Workshop on the Zambezi Valley held at Mana from 1st to 4th May. The notes were augmented by the May Botanic Garden Walk with Tom Muller. If anyone is going to Mana we really would appreciate them checking this guide, particularly the distances as Meg and I spent much time reversing. We would like to smarten up these guides, so please forward any comments or criticisms. Mana is a National Park and plants are protected by law. I am not aware of anyone being prosecuted for eating fruit, although Meg and I were apprehended by an irate official who decided we needed a written permit to examine Dalbergiella pods along the road between Makuti and Marongora. The message is ‘beware’.

On the Sunday morning of the Zambezi Society’s Workshop Dick Pitman introduced the session by asking whether anyone had seen anything interesting along their early morning drive. Meg and I just smiled, here is a summary of what we saw. As an introduction may I suggest the first 500 m from the reception as an afternoon stroll, but do keep an eye open for animals. The rest of this guide is recommended for the early morning when the sun is behind and the trees are easier to see.

Trichelia emetica. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

As all visitors report to reception this is an ideal point from which to begin. The office is situated on the riverbank amongst tall riverine species. Leave reception, 0,0 km, and notice the dark green leaves of Trichelia emetica, Natal mahogany, immediately on the right. Beyond this on an anthill on the left is an Acacia albida whose branches are weighed down with a scrambling caper, Capparis sp. Examine this creeper and see the two hooked spines alongside each leaf. These hooks help it scramble and may deter some herbivores. A small Securinega virosa, the snowberry, also grows on the anthill. It is a common shrub throughout Zimbabwe and the white berries are popular snack during the wet season.

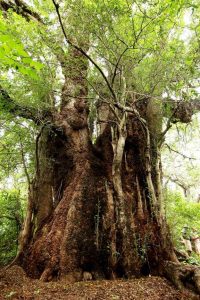

The road then passes more Trichelia and Acacia albida. Pass the closed road on the right, 0,3km, and proceed a further 200 m to an enormous Ficus busei, the Zambezi fig, on the left, 0,5 km. Keep a vigil for animals and walk up to this tree as this species is exclusive to the Zambezi Valley and is one of Mana’s highlights. Notice how the branches spread out to form a tree that is broader than it is high. Examine the dead leaves on the ground and notice their large size. The prominent lateral veins on the under surface, the pointed tip and the distinctly heart shaped, cordate, leaf base. The scrambler in the crown of this fig also belongs to the fig family, the MORACEAE. It is Maclura africana and this specimen is one of the largest in the area. The stem is gnarled and the few leaves near the base contain a milky sap which is characteristic of the MORACEAE. The flowers on Maclura are similar to those on a mulberry. Mulberries also belong to the MORACEAE and, like Maclura, they too may have separate male and female trees. This specimen is male, so from March to May look for tight clusters of cream flowers. The anthers are situated on the ends of spring loaded filaments that flick the ripe pollen into the wind. Naturally the male trees never bear fruit. The female trees produce fruit that resemble over sized mulberries, August to October.

Cleistochlamys kirkii. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Having examined the Maclura turn around and find a bushy Cleistochlamys kirkii whose elongate leaves smell like citrus oil when crushed. It belongs to the custard apple family the ANNONACEAE, and has an edible fruit but unfortunately the clusters of dark purple berries ripen during the wet season before Mana is open to the public. Immediately alongside the fig and opposite the Maclura is Drypetes mossambicensis, a tree with a distinctive colour that results from the way the leaves reflect the light. Notice how the leaf base is often asymmetric and the bark of older specimens peels off in squares. Although elephant browse the leaves this species is seldom knocked down. The yellow fruit, May to June, is edible and tasty. Drypetes often grows alongside larger trees and this could be related to its distribution by birds.

Walk on parallel to the road and find a large Zambezi fig which has fallen forward and developed aerial roots that may help support it. Between this fig and the road there is a Maclura in its more familiar form, as a shrubby bush with shiny dark green leaves and spine tipped branches. It seems improbably that this bush could climb up a tall smooth trunk without the help of side branches. How do you think the last one managed to get into the fig? Could spiny shrubs like Maclura and Capparis provide protection for seedlings that germinated with the bushy clumps? If so they could climb the tree as it grows. Do you think this may have occurred in the case of the large Maclura in the fig tree? If so are the two plants the same age? While you are driving around look for evidence to support or refute this hypothesis. You will soon see that your view on how trees regenerate is vitally important to understanding game management.

Drive past the turn off to Nyamepi on the left, 0,6 km, pass beneath a sausage tree, Kigelia africana, and cross the stream. Prepare to turn right at the next junction, 0,8 km, but immediately before the turnoff is a small clear area on the right with two large Balanites maughamii set back from the road. In the wet season these trees have oval fruit that are edible and are also excellent for killing bilhartzia circaria. Concentrations as low as one fruit to 250 litres of water may be effective. The fibrous kernel, which contains an oil said to rival olive oil, is about 6 cm long and resembles a rugby ball with five lines down the side. It is most commonly seen in elephant dung. Balanites often grows as a bush for many years before sending up a tall straight trunk within a single growing season. These trunks do not become very fat, old trees have slender trunks which are fluted. There are many fine examples on the road out of Mana.

Turn right along the river road and after 400 m look out for a large Maclura in a sausage tree, Kigelia, on the left, 1,2 km.

There are a number of tamarind trees, Tamarindus indica, along the river but few close to the road. On the right at 1,6 km there is a tall tamarind about 50 m from the road and behind a Trichelia. Tamarind flowers are individually small and generally not noticeable amongst the leaves, but this specimen flowered spectacularly in May with the sprays of pink and yellow clearly visible from the road. There is a great debate as to whether the Tamarind is indigenous or was introduced by traders travelling up the Zambezi. In either case it is at home along the river and may be the dominant tree along the river cliffs. Eating the fruit, June to September, is a refreshing experience but it invariably involved sorting through the numerous half ripe, half chewed pods that the monkeys have discarded before peeling back a pod that reveals the sticky brown pulp which is valued in Indian cooking.

After a young baobab on the right, 1,7 km pass the turnoff to the lodges and arrive at a pool on the right, 2,1 km. July like Long Pool, this pool represents an abandoned channel of the Zambezi. Up ahead is one of the vast park like expanses of Acacia albida that makes Mana such a paradise for game viewing. Although many Acacia species do develop tall trunks and flat tops this is not the natural shape for Acacia albida. Prove this next time you are in Harare by examining the Acacia albida that grow alongside the fever trees in the National Botanic Garden. Here at Mana the trees have been pruned by elephant who thrive on the swollen apple ring pods produced during the late dry season. This unusual fruiting time is related to the fact that the tree looses its leaves in the wet season when most deciduous trees have leaves, it then puts them on gain during the dry season. This may be related to the ecology of the tree as it often grows in alluvial sand that is waterlogged in summer. Examine the woodland and notice the lack of juvenile trees. This may result from the heavy game pressure or simply because young Acacia albida seedlings grow better on more recently deposited alluvium. Acacia trees seldom live very long, so it seems unlikely that this woodland will continue as it is for many years to come. What do you think this area will look like when the old tees die? Is there any evidence to show that it may become mixed Acacia albida woodlands like you saw around the reception? From an ecological point of view this change is not ‘bad’ on condition another Acacia albida woodland is developing elsewhere in the park.

The far bank of the pool is lined with Trichelia emetica, Natal mahogany. Although these trees give the impression of being ever green, campers arriving in the late dry season may be alarmed to realize ht they are briefly deciduous during which time they provide little shade. They flower around the same time and fill the air with a heavy scent. Between the road and the pool there are beds of the non-woody Cassia obtusifolia that provide a brilliant display of yellow flowers during the late wet season.

Diospyros senensis. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

The first large tree on the left which is not Acacia albida is Diospyros mespiliformis, 2,5 km. This species is common along the banks of the Zambezi. It is related to the persimmon and boasts a tasty fruit, April to September. The road leaves the Acacia albida woodland 2,9 km, and passes beneath two Kigelia on the left and a Lonchocarpus capassa on the right. After the closed road, 3,2 km a different species of Diospyros forms a bushy under storey on the right. This is Diospyros senensis whose fruit, January to September, resembles an acorn and is less palatable. It is common along the alluvial terrace.

A large Zambezi fig on the left 3,9 km demonstrates another interesting aspect of this tree. Instead of the seed falling to the ground where it may rot in the wet weather or the seedling may be browsed by game, the seeds are distributed by birds or monkeys and germinate in the branches of other trees. Here they grow as epiphytes and derive support but not nutrients from the host. Eventually the roots of the fig encase the host’s trunk and strangle it to death. A detailed study of the host trees around Mana showed that figs usually grew on hosts with a rough bark but few seeds grew in the deep shade of a Trichelia. See how many different hosts you can identify around Mana.

Acacia nigrescens. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

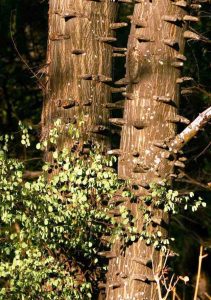

Opposite the fig is a knob thorn, Acacia nigrescens. It has thorny bosses along the trunk and larger leaflets than most other species of Acacia. In the late dry season before the leaves appear this tree is covered in spikes of white flowers. Unfortunately many Acacia nigrescens have been selectively destroyed by elephant in the past decade.

More D.senensis occurs at 4,0 km. On the right at 4,1 km there is an anthill with a tall Combretum imberbe, the lead wood, and the smooth yellow trunk of a different species of fig tree, Ficus sycamorus. This species is the sycamore that Zacchaeus climbed in Jericho; it is not even remotely related to the sycamores of Britain and America. Look along the main branches and notice the bunches of stubby twigs, instead they produce figs amongst the leaves more like the commercial fig tree. All figs are edible although many are watery and tasteless, sycamore figs are widely eaten in ancient Egypt and the Middle East.

After a dip in the road 4,4 km there are tall Lonchocarpus capassa on both sides of the road. Lonchocarpus is called the rain tree because it becomes infested with bugs during the late dry season. These frog hoppers suck out so much fluid from the tree that the excess drips down like rain. The trees are attractive in flower, September to November, although the subtle blue sprays blend with the heat haze and may go unnoticed. Note the distinct browse line on the Trichelia and Diospyros senensis in this area, it allows you to see the twisted trunks of the Diospyros.

Look on the left and pass a Zambezi fig 5,3 km with aerial roots and a small grove of Trichelia. After these find an unusual tree trunk alongside an Acacia albida on an anthill 5,4 km. This strange trunk is well worth a feel, it is smooth but twisted and gouged out. It belongs to Cordia goetzei a tree that has simple dark green leaves. The attractive trunk does not look very functional, it often grows alongside other trees from which it may gain support. Look out for a tall free standing specimen that would disprove this hypothesis.

Continue to where the road bends to the left and notice the dark green shrubby Cassine schlechterana on the left verge. This tree has simple, serrated leaves which are generally opposite. It is one of the few evergreen trees in the Valley. The road then passes Kigelia, A.albida, D.senensis and Trichelia. Cleistochlamys grows on the left 6,1 km before a grove of Combretum imberbe, 7,0 km. All species of Combretum have a four winged fruit, these are small in C.imberbe but they can be found throughout the dry season. The striated bark and the tree’s jagged silhouette are distinctive. If you feel adventurous examine the clump of vegetation on an anthill on the right, 7,0 km. It consists of a C.imberbe growing alongside a Garcinia livingstonei, the African mangosteen, both supporting a scrambling Maclura and with Drypetes and Cassine schlechterana beneath.

A third type of fig tree Ficus sansibarica, may be seen strangling an Acacia albida on the left 7,4 km. Along the main trunk of this species are knobs that bear the fruit. As a result the large ripening figs form an attractive red and green sheath around the trunk. Unlike the Zambezi fig which is restricted to the river and wetter areas, Ficus sansibarica is widely distributed throughout the Valley. Excellent examples grow along the road out of Mana. Examine a few dead leaves beneath the tree and compare them with those of the Zambezi fig. These are smaller, the veins are less prominent on the under surface and the leaf base is not distinctly cordate. Drypetes grows in the shade of these trees.

Xanthocercis zambesiaca. Photo: Petra Ballings. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

The road passes more Zambezi figs and arrives at the spot where I witnessed my first rhino charge 7,7 km. At the time I neglected to notice the tall Xanthocercis zambesiaca on an anthill on the left. The compound leaves on this species have alternate leaflets and the bark peels in a characteristic manner. Here is another hypothesis to test : In the Zambezi Valley Xanthocercis is restricted to anthills whereas in the S.E. Lowveld it is not Facing this anthill with the road behind there is a path that leads off to the right. Along this path is a Xeroderris stuhlmannii which can be identified by hunting for fallen seed, January to August, the seed has two distinct lines down each side of the flattened pod. Further down the path is a Cordyla africana which may look spectacular in full orange flower, July to October. It is interesting to find Cordyla and Xanthocercis so close together as these are both legumes and yet neither of them has the typical pea like pods; Xanthocercis has a shiny black seed covered in an edible but floury pulp; the oval fruit on Cordyla, November to December, is called the wild mango, it may be eaten raw or cooked.

Further down the road 7,0 km is another tall Cordyla growing with Trichelia on an anthill on the right. Although Cordyla and Xanthocercis look similar Cordyla has lighter foliage and the main branches have both vertical fissures that expose a shiny under bark and transverse lines of lenticels, breathing pores. The leaves may be too high but when you find them hold them against the sky and notice the numerous pellucid streaks, these are slot shaped glands that are only present in Cordyla. This tree is infested with a member of the LORANTHACEAE, a parasite that derives its food from the host tree. It is important to realize that you cannot put a moral value on nature, this parasite is not ’bad’, it is neither better nor worse than a lion that eats buck or a buck that feeds on grass. These parasites are eaten by numerous butterfly larvae that cannot feed on the host tree, this increases the species diversity in the area and so adds another dimension to the ecology. Although loranthus grow in deciduous trees they sometimes keep their leaves while the host tree stands bare. How does the parasite persuade the resting tree to provide it with water and mineral salts?

Beyond the Cordyla the road is lined with two of the three scrambling species of Combretum that grow on the alluvial sands. These are easy to recognize in flower but less so when in leaf. On the right a Kigelia is covered with Combretum obovatum, a species with brown to white flowers that are not showy. Instead the leaves on the flowering branches lack chlorophyll and cannot photosynthesize, they are white and perform the role of petals in attracting pollinators to the flowers. The odd white leaves help to identify this species which commonly grows as a dense bush. The second species, C.mossambicense, is generally a multi stemmed shrub but also scrambles. The white shaving brush flowers are easily spotted on the leaf less branches during the late dry season and the young twigs have a fibrous bark that reveals a purple stem. Both of these species have a five winged fruit instead of the more usual four winged fruit that occurs in the third scrambling species, Combretum microphyllum. Visitors to Mana during the late dry season may have noticed the red flowers of this burning bush Combretum in the canopies of other trees. Scrambling generally requires some form of anchorage. Capparis has hooked prickles, Maclura has short spine tipped branches. Combretum uses a different technique. Try to identify two types of branches on these shrubs, firstly the normal photosynthetic branches that form most of the canopy and secondly the long untidy climbing shoots. The leaves on the latter are often small but with prominent leaf stalks. These leaf stalks are not deciduous, instead, they continue to grow after the leaf has fallen and eventually become strong grappling hooks that support the scrambler.

At 8,4 km there is a Zambezi fig on the left with Cleistochlamys in front and a Kigelia and Lonchocarpus on the right. Beyond these 8,6 km are two Zambezi figs, the second strangling a Kigelia. The road passes beneath a Trichelia on the left, Cordyla on the right and enters a patch of Diospyros senensis. See if you recognize the distinctive bark of Combretum imberbe.

Pass the turnoff to Mucheni Camp 9,0 km and shortly beyond the pool on your right notice the patches of stunted ilala palms, Hyphene petersiana. These trees grow like this form for many years before one or two within the clump suddenly get away to become trees. Palms are monocotyledons, their leaves have parallel venation, and once they have developed a trunk they generally cannot undergo secondary thickening which is the process by means of which other trees produce more water transporting vessels. As a result every new leaf which grows saps the limited water supply and so an old leaf must die and fall. As a result palms grow taller as they age, but their crown does not expand. It is therefore important for a palm to sit on the ground and develop a full size crown before it raises this crown into the air.

Pass a Cassine schlechterana on the right and a heavily browsed Maclura on an anthill 93 km. Rhino and elephant do not seem to mind the spines or the milky sap. Before turning left on the road to Long Pool notice the large Xeroderris on the right 9,7 km and the regeneration of Lonchocarpus.

Garcinia livingstonei. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Turn left towards Long Pool 9,8 km. The road passes through a grove of Lonchocarpus 10,3 km before entering a more open woodland with Acacia albida. An anthill on the right 10,6 km has a Xanthocercis alongside which is a Kigelia and an A.albida. On the left notice the distinctive outline of a Garcinia livingstonei. Each of the main branches tapers like a pine tree but instead of growing vertically these branches arch outwards. These trees have dark green leaves that contain a yellow sap. The tasty fruit, the African mangosteen, ripen during the rainy season.

At the next dip in the road there is another Kigelia africana, the sausage tree. This species has large liver coloured flowers that hang on long cords, August to October. When the tree is leafless these cords aid identification. Although each bears a number of whorls of flowers few of these set seed because one seldom sees more than two or three fruit hanging on each cord, December to June. If all the fruit did ripen the cord would probably not be able to support the weight. The flower is one of the classic examples of bat pollination and the fibrous fruit is eaten by primates and rhino.

The bush clumps on the left 11,1 km consist of Combretum obovatum and a different species of Capparis, C.tomentosa. As the name implies the leaves of this species are hairier than the Capparis which was scrambling in the A.albida near reception. Both species have pairs of hooked prickles on the stem. They belong to a family, the CAPPARACEAE, that is rich in mustard oils. These oils are thought to deter herbivores; do you see any evidence to show that this is effective? The capers that provide the mustard oils in tartar sauce are prickled flower buds from two Eurasian species C.spinosa and C.herbacea. There is no reason why our indigenous capers should not be equally tasty.

Beyond these clumps there is a tall overgrown shrub with large pale green leaves. This is Croton megalobotrys and whenever you see it it is a sure sign you are approaching a tributary of the Zambezi. It seldom grown along the Zambezi River itself. All the indigenous species of Croton have two tiny glands that stick out from the leaf stalk on the underside of the leaf at the base of the leaf blade.

The road passes through regenerating Lonchocarpus with clumps of Combretum obovatum. At 11,3 km there is also a Zambezi fig strangling an A.albida, a Cordyla stands nearby.

At 11,7 km the road enters a mopane woodland that has been severely damaged by elephant. Solid stands of mopane, Colophospermum mopane often grow in flat areas where the fine soils are poorly drained and muddy during the wet season. There is generally a high sodium content and the ground is prone to capping, the formation of a hard surface layer impenetrable to water. The elephant appear to concentrate on certain areas in which they fell all the trees. The undergrowth in mopane woodland is often fairly sparse, particularly during the dry season, but once the canopy is destroyed the ground is usually bare. There are different ways to experience vegetation, one of them is to walk into it and absorb its atmosphere. A different exercise which achieves a lot more a lot faster is to lie on your back in the vegetation and experience a “herb’s eye view”. Why not experience this stark landscape and compare it with the taller mopane woodland that lies beyond, 12,1 km. In this taller mopane two shrubs form an under storey, both of them belong to the same family as the caper and so may also contain mustard oils. The first, Boscia mossambicensis, is a 1 m bush with stiff dark green leaves. The flowers, aril to June, consist of a mass of white stamens and are followed by cerise fruit, June to September. The second Corbourea glauca, is a small shrub with grey leaves that release a smell reminiscent of rats’ nests when rubbed gently between the fingers. The first clump of trees on the right that are obviously not mopane 12,4 km contains a Xanthocersis close to the road. Behind this is a tall Diospyros mespiliformis and a Combretum imberbe.

This road guide speeds up now as we were riding into the sun and heading back for breakfast. After more scrub mopane there are a number of Acacia robusta subsp. clavigera 14,1 km which characteristically grow in a belt between the alluvial vegetation and the mopane. This species resembles the more widespread A.karroo but A.karroo does not have a pale bark and probably does not grow in the Valley.

-Kim Damstra

EXTRA NOTES ON ALLUVIAL SPECIES (extracted from the May Botanic Garden Walk with Tom Muller)

Acacia galpinii occurs rarely on the alluvial sands, it has fewer and larger leaflets than Acacia polyacantha which does not occur in the Valley. Acacia tortilis has an umbrella shape and invades old lands in the Valley. Its gum is exploitable and so may be important for communal lands. Prof. Phelps notes that around the Rekometjie Research Station is species has been selectively destroyed by elephant. Acacia xanthophloea, just like the giraffe, does not occur in the Valley, yet it is found in Tanzania and Kenya.

Albizia anthelmintica and Securinega virosa are common on the alluvial sands of the Rukomeche River.

Balanites aegyptiaca grows in the Mopane in the Valley. Berchemia discolor is mainly restricted to the jesse in the Valley, although in the S.E.Lowveld it is more widespread. It often resembles a marula during the dry season, but marula do not grow in the jesse. Cassine as a genus is characterized by breaking rules whose species with alternate leaves usually also have opposite leaves and vice versa. Citropsis occurs on the alluvium, although it is more common in jesse. Combretum kirkii has large fruit like C.zeyheri and is a common climber along small streams at the edge of the jesse. Tom’s plants remain small for a long time before suddenly getting away.

Combretum mossambicensis invades old lands, like those near A-camp that supplied vegetables to the builders of Kariba.

Feretia aeruginescens grows along tributaries in the Valley It also occurs at Victoria Falls and on old alluvial terraces at Sengwa.

Terminalia sambesiaca is unusual in its genus as it has a smooth bark and so may not survive fires well. It grows along tributaries on the middle road to A-camp.

Lecaniodiscus grows along most of the tributaries.

Xanthocercis is briefly deciduous.

Alluvial vegetation depends on the size of the river, alongside the Zambezi Kirkii and Terminalia pruniodes grow on the edge of the alluvial vegetation whereas they both grow along larger tributaries, smaller streams are flanked by Kirkia alone.

FIELD TRIP TO ALAMEIN FARM, BEATRICE, SUNDAY 21ST JUNE 1987

The Watson Smiths were once again our hosts as we revisited this venue from where rain had driven us away in January. This time it was an Arctic blast which tried to do the same, but it seems we are more resistant to cold than wet.

We rendezvoused on the road in the vicinity of the somewhat unusual outcrop of mopanes, Colophospermum mopane. This was the first species we looked at. We noted the paired “butterfly” leaflets with the tiny vestigial leaflet in between. We were also pleased to find a pod, which, when opened, revealed the seed resembling a flattened brain peppered with sticky dots of resin. This is apparently the means of seed dispersal. It is thought that the seed adheres to the underside of an animal’s foot until deposited elsewhere.

Close by was a Commiphora which although without leaves could still be identified as such by the appearance of the bark which looked as though the branchlets had poked their way through soft toffee. By a process of elimination on bark characteristics we decided this was C.mollis. Another seemingly dead tree alongside revealed itself to be Pavetta gardeniifolia by the presence of the black dots in the leaves. We saw a young Pappea capensis which demonstrated the tendency in this species to have a very serrated margin possibly to discourage browsers until the tree gets above the browse line.

As we were close to an anthill it was perhaps not surprising that we should see Maytenus heterophylla. We noted the obovate, upside down egg, leaves on tight fascicles and also observed the notched ends of most of the leaves. A little later we were able to compare M.senegalensis with a pink petiole and a grey blue tinge to the leaf.

Combretum hereroense. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

We next saw the first of several Combretum hereroense. We were shown the four-winged fruit which in this species a. bout the diameter of a 20c piece and a golden brown colour. We also noted the “mouse ear” leaves which supply the common name. The most remarkable point about this species is the fact that one tree may have velvety leaves whilst another next to it may have quite smooth leaves. Apparently the two are the same identical species and there is no accounting for this phenomenon other than that one gets black and olden Labrador pups in the same litter!

We also saw Combretum apiculatum with the commonly seen twist to the tip of the leaves, and C.zeyheri with the tennis ball sized fruit. Also in the COMBRETACEAE family, we saw Terminalia sericea and T.mollis, both of which showed the diagonally braided bark. We also noted the large velvety leaves on T.mollis but sadly, we saw no fruit.

Within the anthill area itself we saw Boscia salicifolia diagnosed by the elongated leaf with a prominent pale midrib. There was also a fair sized Schotia brachypetala which showed the winged rachis to good advantage. The other “special” of the anthill was Cassine transvaalensis with a smallish elongated leaf with sharp serrations. This we later saw as large tree bearing a large quantity of ripening fruit.

Another common denizen of anthills which we saw was Rhus lancea, recognized by the long narrow pointed leaflets, in a tri-foliate arrangement. Harare residents may know this as a street tree lining Glen Shee Avenue in Greendale and Manica Road West near the VID. With this we compared Rhus tenuinervis with a slightly velvety texture on the leaflets which are very rounded with a scalloped margin. A more unusual find was Rhus leptodictya, also with elongated leaflets, but not so much as R.lancea. Also the margin is somewhat serrated and the leaflets tend to have a pinkish tinge especially on the midrib. The odd thing was that we were not on a granite kopje, the usual habitat of this tree.

We saw one Protea. This was P.gaguedi identified by the long narrow smooth leaf, as opposed to the rounded leaf and velvety leaf respectively of the other Highveld species, P.angolensis and P.welwitschii.

We compared Acacia karroo with A.gerrardii and saw that the former has the reddish branchlets and slightly larger leaflets. Another useful field character is the way that the leaves are borne. A.gerrardii tends to have a “wooly fur” of leaves along the branches while A.karroo bears them on longer twigs sticking out from the crown like unkempt hair. From the same area, one member came back with a pod of A.nilotica.

We were fortunate to see an autumn show by a Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia, the duiker berry. Most of the leaves were turning red. Only one fruit was seen. Also going into its autumn colour, but this time yellow, was Monotes glaber, complete with “helicopter” fruit. The dot or “extra floral nectory” at the base of the leaf was also pointed out to new comers as a useful feature.

Strychnos pungens. Photo: Jos Stevens. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Our little group saw a number of other trees of one sort or another, but the one which I most regret missing but seen by another group was a small grove of Bolusanthus speciosus, and whilst not strictly part of the morning walk, it would be a serious oversight not to mention the Strychnos pungens from which a good lot of fruit were collected on the way to the homestead. This is something of a rarity in our parts and this must be about its northern most limit. The bark is rather smooth and the hard leaf has a sharp point at the tip. Most of the fruit collected were green but we were hopeful that they would ripen. A few more ripe fruit were collected later in the day.

-J.P.Haxen

Afternoon walk : Following lunch break at the main farmhouse with its very fine selection of extremely large trees in the garden, we walked out from the house. The entire area near the two farm houses is marked by the great size of the indigenous trees. We were shown a non indigenous pink cassia which had been planted in the garden recently, from another location, where it had made no progress since being planted out several years before. Since the replanting it had put on a remarkable burst of growth, so perhaps there is a high water table or nutrient level in the area.

Parinari curatellifolia were most impressive, being of enormous size, in very heavy flower and some in fruit. None of the fruit was anywhere near ripe, yet there was everywhere evidence of these fruits well chewed, and still wet on the ground. Bush babies are known to eat green marulas, so perhaps they were responsible for the eaten Parinari fruit. We also admired two enormous Kigelia africana, sausage trees, in the garden. The one nearer the house has in the past been responsible for a broken roof and a car windscreen. Guy Watson Smith related how he had watched Myers Parrots shredding and eating the fruit.

There were a least three species of Strychnos, S.spinosa, S.cocculoides and S.pungens and some very large Monotes glaber. Much fun was derived from the discovery of Flacourtia indica in ripe and near ripe fruit. Usually someone or something has always been before. The fruits were quite pleasant and contained several rough and stony seeds. And so back to the bus stopping on the way to admire Guy’s collection of ducks and swans. Many thanks to the Watson Smiths for all the hospitality and the venue.

-C.M.Haxen

Dick Hicks Chairman