TREE LIFE

NOVEMBER 2022

Dracaena draco Photo by Roger Williams

Hi Everyone,

Welcome to Tree Life 507 for November 2022! A chance meeting on the verandah of a supermarket café in Groombridge led to me getting this spectacular photograph from the proud owner of a Dracaena draco, more commonly known as the Canary Island Dragon Tree. This year is the best it has ever flowered with six spectacular racemes exploding like fireworks from the body of the tree. The owners’ chest buttons were bursting with pride, but now of course the flowers have turned into fruit and these are busy dropping off and into the perfectly-kept swimming pool. As you all know the closest relative of this tree is Dracaena cinnabari which occurs on the other side of Africa on the island of Socotra. The rich red gum of this tree gives it the grander moniker, Dragon Blood Tree!

Tree of the Month: Baobabs, a national treasure under pressure

By Ryan Truscott

Baobab Tree Photo by Ryan Truscott

My family and I have been enjoying baobab juice, a new product developed by Dairibord as part of its Cascade range.

The company says it saves money by not having to import ingredients, as it does for the other flavours.

But just how sustainable is the use of Zimbabwe’s baobab trees?

In a new study published in the African Journal of Ecology, a group of researchers says this depends a lot on what land tenure system is in place.

The team studied the use of baobab trees on state, communal and private land in the Nyanyadzi district. Most of us who have travelled to Hot Springs and Masvingo from Mutare will be familiar with this route and the mighty baobabs that line it. These are the ones the team studied.

Baobabs on state-owned land were found to be the most heavily exploited, for both their fruit and their bark, which is used to make the beautiful floor mats that are also a prominent feature at numerous roadside stalls for sale to passing motorists.

When bark is over-harvested, fruit production goes down.

Baobabs growing on private land were found to produce an average of 109 fruit per tree; trees on communally-owned land 69, and those on state-owned land just 23.

“Bark harvesting from trees under state tenure was intensive, with trees harvested up to the branches… and on average four times over a 2-year period,” the study says.

“Heavily debarked trees produced fewer fruits than those under private and communal tenure.”

There are other pressures that could have implications for the future conservation of baobabs, which can live for up to 4,000 years.

With prolonged droughts expected to become more frequent, the shallow-rooted baobabs will be sensitive to climate change. For instance, the black soot disease that affects many of the trees in Nyanyadzi — and previously thought to be linked to excessive bark harvesting — is more likely a result of drought. It became particularly severe in the wake of the 1992 drought, the study says.

There is some consolation though. The Forestry Commission has been monitoring affected trees in Nyanyadzi since 1949. More than 70 years later, they’re still doing fine.

We’d all be a lot poorer without baobabs. Their protection, sustainable use, and regeneration is vital.

Some farmers in Nyanyadzi are growing baobab seedlings, and I recently heard of an initiative by someone in Harare who is encasing baobab seeds in balls of mud and cow dung.

You can collect some of these seed balls before you go to a baobab region and toss them out somewhere where they have a hope of germinating.

Planting trees is an investment in the future; baobabs even more so. It means those who live 4,000 years from now will also enjoy the benefits of these national treasure.

Mt Nyangani and its Surrounds

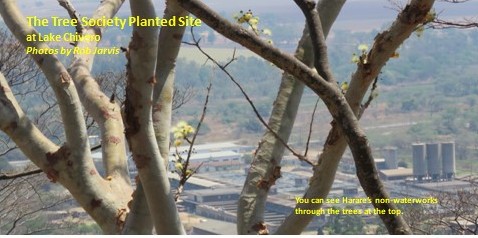

Text and photos by Rob Jarvis

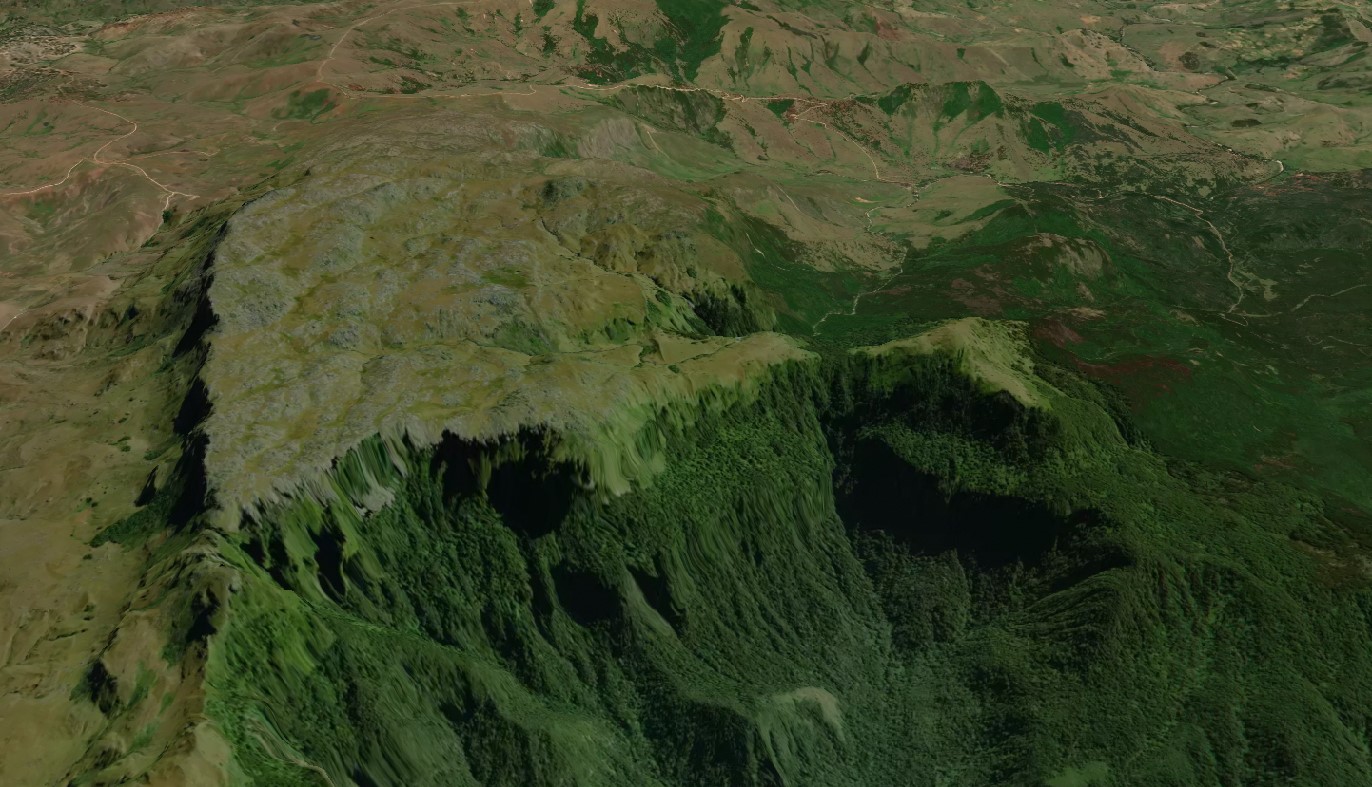

Mt Nyangani Gaia Satellite Screenshot by Julian Purse

Just a week ago we spent a couple of nights camping on the alto-plano of Mt Nyangani. The weekend was supposed to be that of the annual game count but unfortunately official permission had not come through for this to take place. However the Mountain Club, who each year are given permission to camp on the plain behind the ridge that harbours Mt Nyangani, were allowed to continue with the tradition of being the only people allowed to camp actually on the mountain. Nyangani never disappoints and in the 6 or 7 years that we have been undertaking this operation, on at least one of the two nights spent up there, the ancestral spirits vent their anger at the intruders and howling gales, torrential rains and all other kinds of banshees and wailers hurl themselves at our tents in the dead of night. So far we have survived and no one has gone missing. The National Parks guides assigned to us never spend the night up there, they rather retreat down the mountain at last light and reappear at dawn. This year the mountain gave us two nights of extreme weather with thunder and lightning coming out of clear skies and then a whole day of swirling mists alternating with baking sunshine.

On the satellite image above you can see clearly just what a special place the Nyanga National Park is in the overall scheme of things at the apex of the Eastern Highlands. Most of the area is a large spongy grassland, tussocky with almost no natural tree cover at all, except in very sheltered rocky areas or hidden in folds in the landscape. However the eastern slopes of the mountain are clad in immense, impenetrable indigenous forests. You enter their precipitous slopes at your peril. Mt Nyangani is right in the middle of the left hand ridge you can see above. Little Inyangani is the grassy promonotory on the middle right of the photo, just above the text. An ancient civilisation left their dry stone walls on Little Inyangani, a wonderful vantage point, that would be very easily defended, but now the tussocky grasses virtually hide everything. The grassy plains feed two great river systems, the Gairezi flowing north and the Pungwe/Honde systems that flow south, east and then south again to eventually leave Zimbabwe and empty into the great feverish bay behind Beira on the coast. In 2012 we mounted an expedition where we were going to walk down from the source of the Gairezi, just behind Mt Nyangani peak, and follow the river all the way down to the fishing cottages. However we didn’t have the advantage of Gaia and we stumbled over the steep cliffs down into the Gairezi river valley and after struggling for a full day, just managed to make around 400 metres through extremely thick heather. We had to abandon ship and retreat up the mountain, past the peak and down to the carpark. Mission unaccomplished. On the way in we were trapped for a while in extremely thick mist on the eastern ridge from Tucker’s Gap, heading north and had to sit in swirling mists.

On the satellite image above you can see clearly just what a special place the Nyanga National Park is in the overall scheme of things at the apex of the Eastern Highlands. Most of the area is a large spongy grassland, tussocky with almost no natural tree cover at all, except in very sheltered rocky areas or hidden in folds in the landscape. However the eastern slopes of the mountain are clad in immense, impenetrable indigenous forests. You enter their precipitous slopes at your peril. Mt Nyangani is right in the middle of the left hand ridge you can see above. Little Inyangani is the grassy promonotory on the middle right of the photo, just above the text. An ancient civilisation left their dry stone walls on Little Inyangani, a wonderful vantage point, that would be very easily defended, but now the tussocky grasses virtually hide everything. The grassy plains feed two great river systems, the Gairezi flowing north and the Pungwe/Honde systems that flow south, east and then south again to eventually leave Zimbabwe and empty into the great feverish bay behind Beira on the coast. In 2012 we mounted an expedition where we were going to walk down from the source of the Gairezi, just behind Mt Nyangani peak, and follow the river all the way down to the fishing cottages. However we didn’t have the advantage of Gaia and we stumbled over the steep cliffs down into the Gairezi river valley and after struggling for a full day, just managed to make around 400 metres through extremely thick heather. We had to abandon ship and retreat up the mountain, past the peak and down to the carpark. Mission unaccomplished. On the way in we were trapped for a while in extremely thick mist on the eastern ridge from Tucker’s Gap, heading north and had to sit in swirling mists.

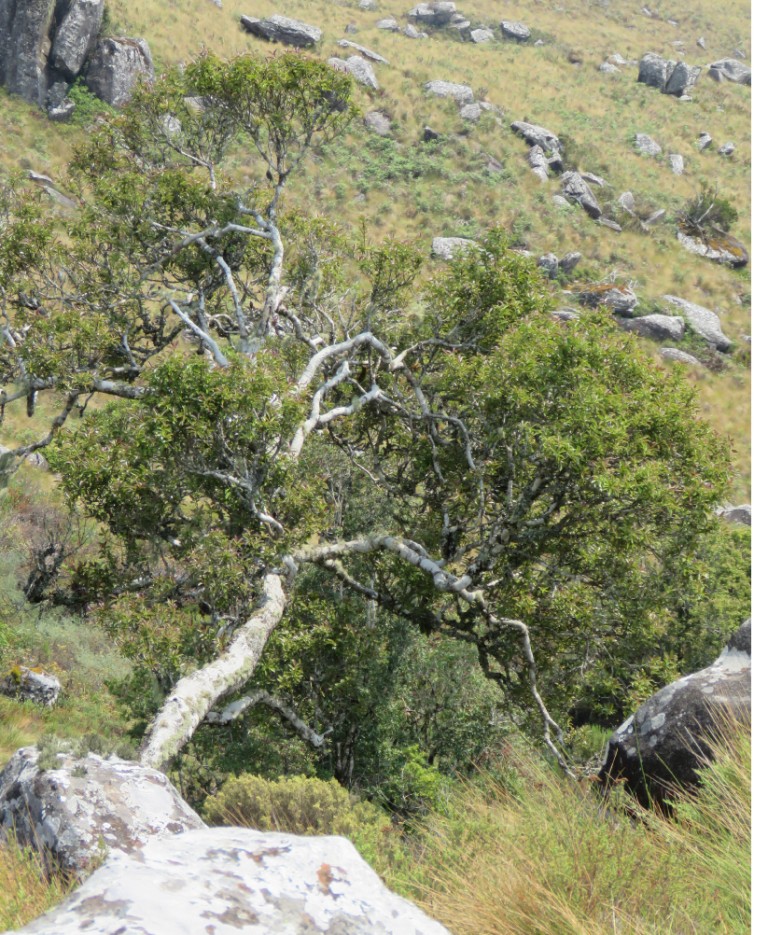

Suddenly there was a break and in the grassland in front of us appeared this beautiful patch of forest, seen above. It is now part of Far and Wide’s Turaco Trail and makes a welcome overnight stop for weary hikers. Exactly why this particular patch of forest exists is amazing, it is surrounded on all sides by the fire-prone grasslands of the alto-plano and the east/northeasterly winds that prevail on the back of Nyangani invariably result in fiercely hot fires that reduce trees to ashes. It would make a great study opportunity for a budding eco-botanist to examine the species to be found therein and to determine the reasons why it exists, like a little piece of Heaven.

On the alto-plano there are very few trees and on the 19 kilometre hike we undertook on Saturday, last week, we only saw a few pines, probably P. patula, and here and there some Aloe arborescens, scrabbling among rocks and just making the tree category, but looking very ragged. The pines however, are on the march and they can be seen coming up the hill from the Nyama and Gairezi valleys and really need to be dealt with by National Parks before they become really well and irreversibly, established.

On the alto-plano there are very few trees and on the 19 kilometre hike we undertook on Saturday, last week, we only saw a few pines, probably P. patula, and here and there some Aloe arborescens, scrabbling among rocks and just making the tree category, but looking very ragged. The pines however, are on the march and they can be seen coming up the hill from the Nyama and Gairezi valleys and really need to be dealt with by National Parks before they become really well and irreversibly, established.

On this page you see some of the few indigenous trees that do occur in tiny pockets on the alto-plano behind Nyangani. The odd tree-fern, giant heather, an odd lavender tree, almost wrenched right out of the ground in its lonely spot and along the path, suddenly a brief strip of fire-ravaged trees that have managed to co-exist with some jumbled boulders but are showing much sign of stress as they recover from last year’s fires. In the background of the last picture you can see just how unusual is the little patch of forest mentioned in the pages above.

Outing to National Botanical Garden – 1st October 2022

By Tony Alegria

The day started rather gusty and coolish but once the wind had died down it became rather warm. Present were the ladies: Dawn Siemers, Meg Coates Palgrave and Teig Howson. Men: Jan van Bel, Jim Dryburgh, Mark Hyde and myself.

We started off with a purpose – to find out if any fig could be diagnostic, in order words if you had a fig in your hand, could you possibly name the fig tree it came from. To do this we had to collect as many samples as we could and that’s just what we did! The other thing we did was to test the fig leaves to see which of them cracked the loudest although they were green. It kind of followed that the thicker and stiffer the leaf was, the louder the crackling. Ficus usambarensis had the loudest crackling but unfortunately the tree had no figs at all. Also without figs were: Ficus Burkei, Common wild fig and Ficus chirindensis. Fairytale fig. Although the Ficus religiosa, Sacred fig had new tiny figs, they were out of reach.

On the other hand, Ficus benghalensis was full of dried up figs from the previous crop. These figs have no stalks (Sessile) and by the looks of it, was the only fig tree not to drop its figs like all the others do within the National Botanical Garden. The only other figs to have sessile fruit were the Ficus glumosa, African rock fig, Ficus lyrata, Fiddle leaf fig and Ficus cyathistipula, African fig tree.

Ficus sur & F. sycomorus Photo by Tony Alegria

We collected figs from many trees including one unknown fig but we didn’t get them from all the trees – there are just too many in the garden and many of them are unknown. Tom Muller used to know all of them but unfortunately he is no longer in Zimbabwe and the records he kept seem to have been lost.

The identity of the two figs, left, can be told purely by the branchlets they grow on. The Ficus sycomorus, Sycamore fig is pear shaped and grows on short branchlets whilst the Ficus sur, Broom-cluster fig grows on long tangled up branchlets.

Figs are diagnostic Photo by Tony Alegria

We found the figs above to be diagnostic: Fig 1 – Ficus benjamina, Weeping fig from South Eastern Asia & Australia is rather small, has a very short stalk and is red in colour; Fig 2 – Ficus elastica. Rubber fig from North Eastern India, Nepal and through to China, has a short stalk and longish look. Rather strange that these two tiny figs come from such large trees!

Fig 3 – Ficus ingens. Red-leaved fig is indigenous and becomes pink or pinkish when ripe. It also has a rather short stalk.

Fig 4 – Ficus glumosa. African rock fig is indigenous, has no stalk and becomes yellow when ripe. The other feature is that it has a hole at the end leading to the ostiole.

Fig 5 – Ficus bussei. Zambezi fig is indigenous, warty, is a bit pear-shaped and has a stalk about half the length of the fruit.

Fig 6 – Ficus ottonifolia. Birds-egg fig has its southern range in Northern Zambia. This is more of a bush than a tree and the figs grow on short stalks on what look like large caterpillar shaped knobs on old wood.

Fig 7 – Ficus sycomorus. Sycamore fig is pear shaped, has a short stalk and grows on short branchlets. These branchlets are to be found on old wood.

Fig 8 – Ficus sansibarica. Knobbly fig is indigenous and grows on knobs on old wood. Sample above is not full size. They are most attractive when ripe as they turn purple.

Fig 9 – Ficus cyathistipula. African fig tree comes from the tropical forests of Africa, has no stalk and has a spongy feel with a hard centre when squeezed.

Fig 10 – Ficus lyrata. Fiddle leaf fig from western Africa has no stalk and where as many figs have warts, these have dimples and are a dark green.

Fig 11 – Ficus vallis-choudae. Haroni fig has the biggest, furriest, fruit by far. The one shown above is only half size!

Figs Photo by Tony Alegria

In no particular order, the figs shown above came from Ficus bizanae, Ficus bubu, Ficus dicranostyla, Ficus fischeri and an unknown fig. I would not consider any of them to be diagnostic!

Tabebuia heterophylla Photo by Tony Alegria

While out looking for different figs, we saw the following trees in flower:

Fernandoa abbreviata with its large colourful flowers – most of them had already stopped flowering.

Millettia dura with its purple flowers – some old but lots of new buds coming along.

Rothmannia manganjae – this is a tree we found recently within the Low Altitude Rainforest.

Erythrina abyssinica with its red flowers.

Tabebuia heterophylla with pink flowers – now beyond its best by date, it was magnificent a couple of weeks ago.

Erythrina sp. Photo by Tony Alegria

Tabebuia heptaphylla now looking great with its pale pink flowers.

Bolusanthus speciosus just coming into flower with its wisteria-like purple flowers.

And then this small Erythrina (left) growing close to the pink jacarandas! I have no idea what it is.

When we arrived back at the car park, we laid out all the figs and had a good look at them. We came to the conclusion that more figs than we thought are diagnostic!

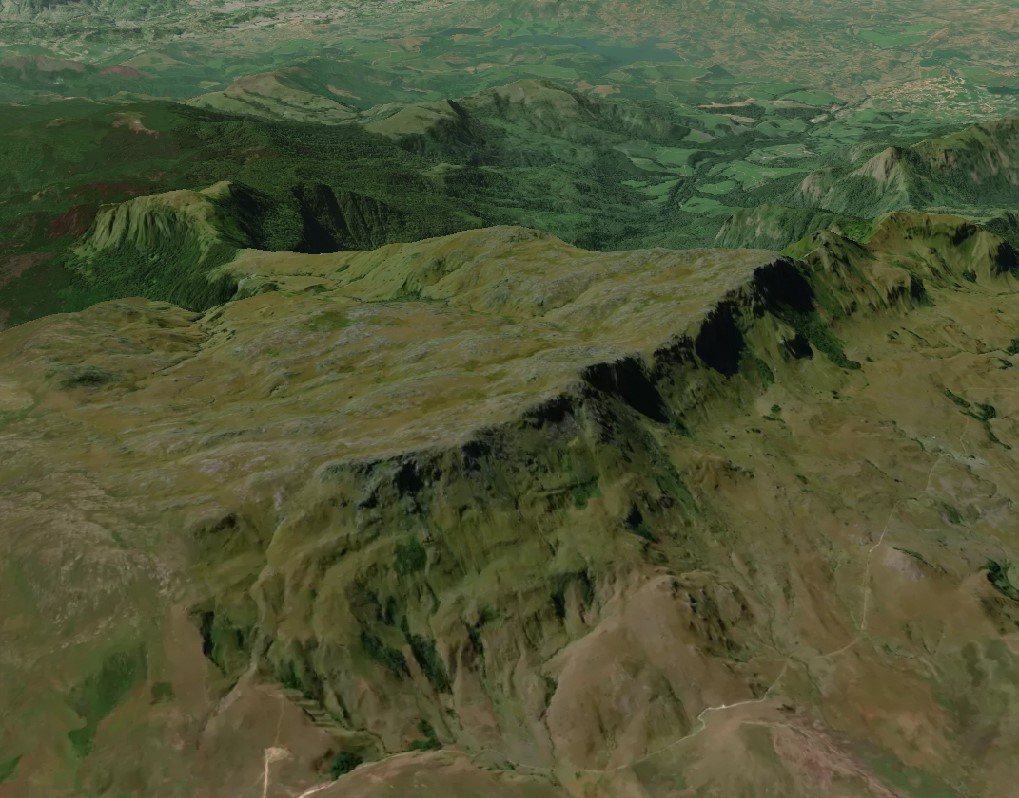

Photo from Gaia By Julian Purse.

So we leave you this month with another view of Mt Nyangani, this time looking from the south-west. The main peak is middle right, Little Inyangani on the top left and behind the mountain massif is the verdant Honde Valley with the tea estates of Eastern Highlands and Aberfoyle visible. Most of what you see as dark green vegetation in the mountain slopes holding Little Inyangani to ransom is dense indigenous forests with towering trees on terrifying slopes. The only reason that they are intact is because access is all but impossible on such steep slopes. However don’t count on it for both in Nyanga and a couple of weeks ago in Stapleford we saw mass extraction of whatever existing timber there was available. In Nyanga National Park it was largely the cutting down of the alien invasive wattles, but fires immediately afterwards just proved that these trees, indeed, are encouraged by fire.

Enjoy November, with the inevitable rain that the month will bring to someone, somewhere.

TREE SOCIETY COMMITTEE AND CONTACTS

Chairman Tony Alegria tonyalegria47@gmail.com 0772 438 697

Vice Chairman Rob Jarvis bo.hoom52@yahoo.com 0783 383 214

Honorary Treasurer Bill Clarke wrc@mweb.co.zw 0772 252 720

Projects Jan van Bel jan_vanbel@yahoo.com 0772 440 287

Venue Organiser Ann Sinclair jimandannsincs@zol.co.zw 0772 433 125

Tree of the Month Ryan Truscott ryan.kerr.truscott@gmail.com 0772 354 144

Secretary Teig Howson teig.howson@gmail.com 0772 256 364