TREE LIFE

APRIL 2022

Resiliency of a Baobab Photo by Rob Jarvis

Hi Everyone,

Welcome to the 500th Issue of Tree Life!!!!!! It really is quite a milestone for our Society to have produced 500 issues of Tree Life. To pander to the grandeur of the occasion we are centering this issue around the baobab, one of the largest trees to be found on our continent and almost certainly one of the oldest. However it is unfortunately one of the quickest trees to completely disappear once it starts to rot, although from an ecological point of view, it is perhaps a treasured member of the ecosystem because it can be totally recycled from a centuries old tree to nutrients and mulch for the next generation of savannah life. Baobabs are renowned for being able to self heal and to cling to life after they have fallen and the example above looks almost exactly the same as it did more than 150 years ago when Thomas Baines painted his famous copse of baobabs on his way to Victoria Falls.

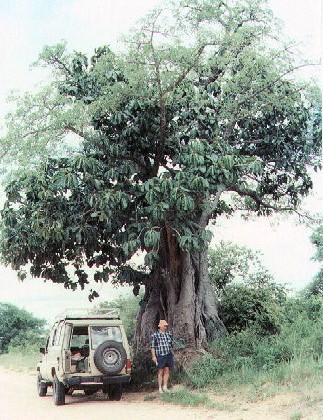

Baobab in Nigeria Photo by Rob Jarvis

Whilst on the subject of travelling in Africa and being struck by the appearance of the various baobabs encountered, I saw the baobab on the right in the middle of a 100 000 hectare flood irrigation scheme in northern Nigeria near the city of Kano. At the time one could travel to those parts without too many problems. However the situation rapidly deteriorated over the 7 or so years that I made regular business trips to Nigeria and now as an obvious foreigner you would not get within sight of this tree without risking abduction and perhaps worse by Boko Haram. So luckily I photographed the tree, printed the picture and gave it to a local artist here in Zimbabwe, Sue Christian Bell, who did an amazing water colour of it and now it hangs on the wall of the home of one of our daughters in Perth, Australia. “Solitary trees, if they grow at all, grow strong.” Powerful words from that great statesman, Winston Churchill and I am sure he had just such a tree in mind, far from any friends, standing quite alone, but very strong and rich with character.

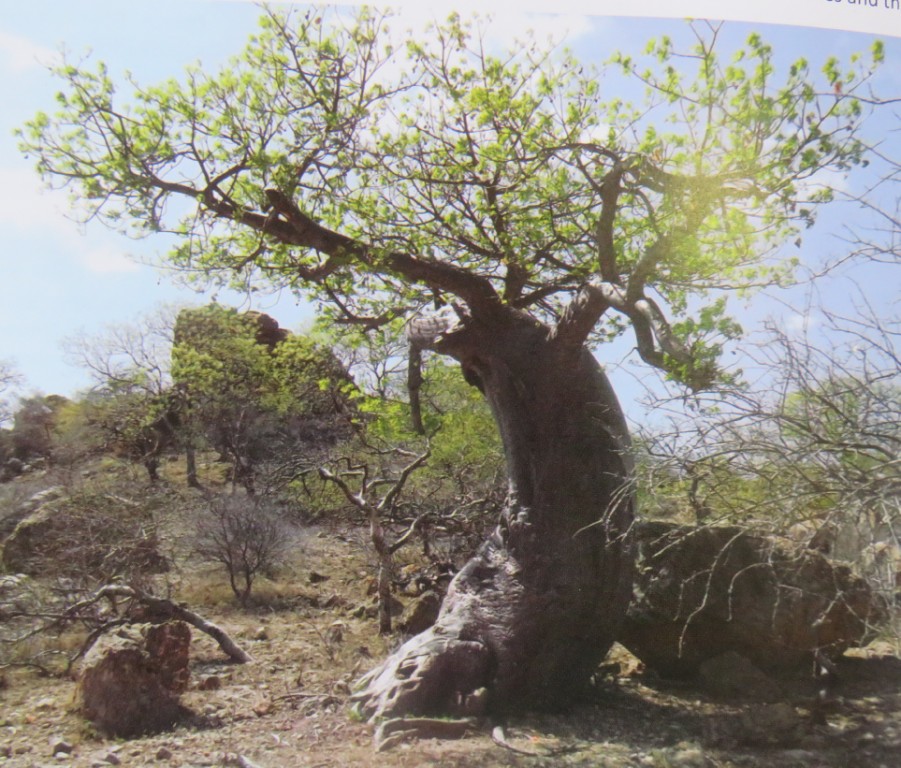

Baobab in Sentinel Ranch Photo by Rob Jarvis

And back here, in the far south-western corner of Zimbabwe we went to see the dinosaur fossil embedded in the rocks near Sentinel Ranch, and there in that harsh arid environment where even Mother Nature herself appears to be against the growth of any living creature was the amazing baobab seen below, left. It was a terribly hot, stinking day, that one could only experience in the Beitbridge area and it really did look as though this baobab had felt exhausted and just felt it was “The Tree that had to Sit Down.” However it was November and there had been a hint of rain further upstream along the Limpopo and rain in the hinterland around Bulawayo and Matobo Hills and the trees had just started to send out their fresh new growth. Again I gave a photo to Sue Christian Bell to convert to a tree portrait and we have this very tree, preserved forever in our house, as a piece of exquisite art. If ever the mantra “A luta continua” has meaning, it is hereabouts in the Limpopo Valley.

When a baobab dies Photo by Rob Jarvis

Above you can see a fallen baobab after less them one year after tumbling to the ground. The rapid transition from healthy living tissue to a mass of crumbly, fibrous vegetative material is extremely rapid and inexorable. This was seen and photographed in November 2021 and I am sure by November 2022 it will all be gone. Not even a fingerprint left behind by a magnificent tree that stood proudly on the approaches to Makaniwa pan when coming from the Runde River crossing.

Baobab supporting a fig tree Photo by Mark Hyde

Tall tree Tale

On a botanising trip to Mayo via Headlands and returning via Murewa on New Year’s Day 1998 my children, aged 11 and 12, spotted this Baobab but were intrigued by the colour of the crown. The mystery began to deepen but then unravelled as Andy MacNaughtan and Dad (Mark Hyde) both said it was a fig.

It was finally identified as an Adansonia digitata L. supporting a Ficus lutea. We enjoyed a wonderful picnic lunch in its shade.

Mark, Linda, Robert and Andrew Hyde with Andrew MacNaughtan

Dwarfed by a tree! Photo by Rob Jarvis

It is only when humans can be photographed in and around the giant cathedral-like forms of mature baobabs that one can appreciate the enormity of them. The fantastic thing about the Adansonia Family is that they can grow for so long, literally in millennia or thousands of years. The only difficulty is to actually, accurately measure them for they have no regular seasonal growth rings like normal trees. They swell with abundant rainfall and moisture and shrink in bad times. Baobabs almost invariably develop internal hollows and the older trees often become a circular wall around the space that was once the heart of the tree. There is no evidence of age in the heart.

Baobab tree showing age? Photo by Rob Jarvis

Baobabs have a sort of storage tap root when young but as they grown they rely on widely spreading surface roots that can venture 50 or more metres from the tree itself. They absorb water from rain and sometimes these surface roots can be up to a metre high near the stem. Probably due to early damage one can often find big blocks of baobab trunk growing separately from the main stem like in the picture right seen at Gona-re-Zhou in our southeastern Lowveld.

In Nigeria and West Africa generally homesteads had baobabs planted around them as a source of green leafy vegetable. The trees are much-coppiced and not particularly big so the leaves are easy to harvest.

Baobab tree showing age? Photo by Rob Jarvis

A baobab is a baobab, of that there is no doubt, although the distinction of two different species on mainland Africa and Arabia was a recent development. To me the mystery was more why there are not many more clear differentiation of separate species given that the baobab we know as Adansonia digitata and now also as A. kilima (which latter species, has distinct floral and pollen characteristics and fewer chromosomes), both occur over very wide ecological and environmental range from South Africa right up to Ethiopia in the northeast and along a broad swathe of sub-Saharan Africa right to the West coast. You can find them growing in deserts, in forest fringes, on islands in the middle of salt pans, on rocky ledges on kopjes and in waterfalls. In Madagascar the endemic baobab species number 6, Adansonia grandidieri, A. madgascariensis, A. perrieri, A. rubrostipa, A. suarezenisis and A. za. Why do they have so many and we so few?

Some baobabs become very famous and it is rather tragic that a significant number of the largest specimens known are starting to die off and unfortunately in many habitats there does not appear to be a clear succession plan. In the densely populated game preserves of Hwange, Mana Pools and the Gona-re-zhou National Parks for instance, you only rarely see young baobabs growing healthily. Around heavily grazed water points even the older established trees are being decimated beyond repair and some major interventions have taken place with sharp rocks, dead hardwood trees and even diamond mesh fencing affixed to the outside of the trees to try and provide some protection.

Baobab tree in Greenwood Park Photo by Rob Jarvis

What interests me however is just how these baobabs survived fluctuating pachyderm populations in the past before the weapons of man and then the demarcation of National Parks and anti-poaching became such a determining factor in the survival of innumerable elephant and the demise of baobabs.

Right is the largest known baobab, in Harare, growing right out of its normal habitat in Greenwood Park in the heart of the Avenues in Harare. It has been very happy here, flowering and setting pods almost every year for at least a decade and just a couple of weeks ago I checked on its form and found that a couple of huge branches had taken a tumble. They were covered in heavy pods and these probably contributed to the tree’s susceptibility to heavy winds swirling around. Let’s hope the wound heals and that the tree continues to thrive.

Young Baobab fruit Photo by Rob Jarvis

Fresh baobab fruit developing in Greenwood Park, obviously well pollinated by a bat, a night-ape or a hawk moth, tick your preference.

And so we come to the end of the this Tree Life 500. I am afraid I have covered largely trees that I have recently known personally and I shied away from downloading pictures that are ostensibly free to print from the internet. It seems that many such indications are not true and I don’t think our Society could successfully fight an intellectual property suit in the courts outside our Zimbabwe dollar realm. It also made me realise just how vulnerable our own records are as files I saved from earlier computers on hard disk drives seem impossible to open and I am just about to migrate to a new laptop. In any case they are saved as compressed files and I would have to go through them laboriously to find choice pictures. Let’s hope my new machine is more user-friendly because my old one is well and truly clogged-up.

Indaba Tree in Tuli Circle Photo by Rob Jarvis

Although it is not very fashionable to think much of the pioneering types who came to this country back in the 1890’s a recent visit to the Tuli Circle reminded us of just how tough it was for these folk to make their way into the hinterland of Africa. The baobab left is where their wagons would have rested up for the last night before they reached Fort Tuli on the banks of the Shashi River. Well known names and initials can be seen carved into the bark of this baobab and the next days journey would be a maximum of about 12 to 15 ‘bone-rattling kilometres. And it is still very bone-rattling today on pneumatic tyres so Heaven only knows how bone-rattling it must have been on wooden and cast iron-rimmed wheels.

But a hundred and thirty-plus years later the baobab endures, visited far less frequently than it was in the 1890’s.

Photo by Rob Jarvis

Above, the llala palm which is often found in the same habitat as Baobab Trees. This particular photograph was taken at Gona-re-Zhou.