TREE LIFE

June 2020

The Tree Society of Zimbabwe is celebrating it’s 70th year. What an achievement considering all the difficult times this little country has been through during the last 70 years. Whilst I have been re-typing and then uploading all the newsletters of the Society onto the Website I have been amazed at the energy and tenacity of all the folk who, over the past 70 years, have been involved in the planning and then execution of all the many projects that the Society has been responsible for in spite of political unrest, fuel shortages, call ups, mass migration, more fuel shortages, hyper inflation, more fuel shortages, more hyper inflation more fuel shortages and then to top it all Covid-19. Does this not typify Zimbabwe, we make a plan?

From the vision of the first Chairman to form such a Society to gather together folk of like minded interest and a love of all things to do with the habitat of trees and all that go with them in 1950, the Society has kept together a group folk who look forward to the monthly all day Sunday outings or the Saturday afternoon snoops around interesting gardens, usually with a nice tea thrown in, or, perhaps most of all, the Saturday morning walks in our wonderful National Botanic Garden, where there is something new or exciting on every visit.

So, apart from our various Chairpersons who have held the Society together, we have to give very grateful thanks to all the farmers who, over all the years, have allowed us to explore the exciting corners or their farms, to the folk who have opened up their homes and gardens for us on Saturday afternoons and to the creator of the gardens, Tom Muller, and now Chris Chapano, who is trying to hold this National treasure together under almost impossible odds.

So, what is our vision for the next 70 years, or even just 10. The scary thing I have observed whilst updating the Website is that the active members in 1980 are STILL most of the active members in 2020, most of us getting towards our Sell by dates, some of us not so mobile any more, but all of us with still a deep desire to get out into the bush, to look at trees and flowers and grasses and fungi and birds and bees and beetles. The combined knowledge of the group is amazing and exciting, the nature of our passion is at a slow pace, each tree or bush or orchid or bit of fungi needs debate and discussion. Maybe it is this that puts the fast moving young off, maybe we need a new passionate group of botanists and zoologists at the University of Zimbabwe like Hiram Wild and Einar Bursell and Fido Phelps and John Loveridge and teachers like Alec Siemers and Keith Coates Palgrave and Piet de Bruyn et al to inspire the next set of Lyns and Kims and Phils and Cheryls and Megs and Marks, I feel sure that the future of our Society lies in the hands and natural enthusiasm of our Ryans and his Sam and Cassia?? This is an earnest plea???

Enough ramblings and fantasizing and on with the show. Because of Covid-19 we held a very different kind of Annual General Meeting. I am not sure what we thought the response from members would be, and were certainly not surprised when only 7 out of all our members acknowledged having seen, not necessarily read, the different reports. We are really appreciative of the kind comments made and the acknowledgement of this way of fulfilling our obligations by these few members. We have adhered to the requirements of the constitution of the Society. We have a Treasurer’s Report, a Chairman’s report and now Minutes of our cyber meeting, (albeit they very short) so all requirements have been met in spite of Covid-19. All members have already seen the Chairman’s and Treasurer’s reports, but these were not recorded in a Tree Life to go onto the Website and so will appear in next month’s Tree Life.

And as we have no upcoming events and no outings to report on I am grateful, as Editor, to have received a super Tree of the Month from Ryan, a most interesting note on a very rare tree from Ian, a note on parasites from Mary Toet with another from Meg, and a very topical note on Moth caterpillars also from Mary Toet, thank you, all of you.

Read on and enjoy.

-Mary Lovemore

TREE OF THE MONTH — AN ICON OF THE EASTERN HIGHLANDS STRELITZIA NICOLAI

Strelitzia nicolai. Photo- Ryan Truscott

My children call them “banana trees” but they’re not.

They are in fact Wild strelitzias, Strelitzia nicolai, and they have been flowering this past month in our garden in Mount Pleasant.

The large leathery leaves clustered at the top of the stems do give the trees a banana-like appearance, but they are in fact from a different family: Strelitziaceae as opposed to Musaceae

In Zimbabwe Wild strelitzias grow in deep valleys in the Eastern Highlands, where their flowers attract the attention of the Gurney’s sugarbirds an unusual species with a long tail, a curved bill and a russet chest that gets birdwatchers twitching with excitement whenever they see one.

Strelitzia nicolai flowers.- Photo- Ryan Truscott

One of the most eye-catching features of this fascinating tree are the multi-storey flowers.

Each boat-like spathe grows out of, and at right angles to, the one below. The process is lubricated by a secretion of mucus-like fluid that glints in the sunlight. “Trees of Southern Africa” notes that a column of flowers can reach up to five-high. The elaborate arrangement of blue and white petals and sepals resembles the feathers growing on the crest of an exotic bird, hence the tree’s other common name: the Giant white bird of paradise. It echoes the name of its cousin, the Crane flower, Strelitzia reginae: that South African shrub so beloved of Zimbabwean gardeners.

Strelitzia nicolai seeds. Photo- Ryan Truscott

The flowers aren’t the only striking feature of S.nicolai. At this time of the year the tree is scattering its seeds, small and black with furry orange caps, released when the three-lobed woody seed capsules split open.

It seems it isn’t just my children who have mistaken Wild strelitzias for banana trees.

Chimanimani resident and Tree Society member Tempe van de Ruit told me that one of the routes up into the mountains is even named Banana Grove after the trees.

“There was a wonderful grove of strelitzias in this valley and one would often come across a herd of eland there,” Tempe said. “The Donkey Path which goes along the edge of the cliff on the north edge of this valley was used by donkeys carrying cement to build the mountain hut. One day a donkey with its load fell off into Banana Grove. It survived.”

Worryingly, she says there are far fewer strelitzias around now than there were 60 years ago, possibly due to the effect of fire and droughts.

Miombo double collared sunbird on Strelitzia flower. Photo- Ryan Truscott

In his book Veld Sketchbook, published nearly 50 years ago, the nature writer and artist Jeff Huntly wrote of how the shiny leaves of Chimanimani’s Wild strelitzias would “catch the sun and glitter with silvery light.” He said the visual effect of this on the eastern flanks of Pork Pie Hill above the village would be “often mistaken for water glistening on the steep rock-faces.”

The Gurney’s sugarbirds, he added, could be seen “sitting in the flowers for long periods chattering to one another.”

It will be a sad day if human activities collude to rob the landscape of this iconic tree and the creatures that depend on it.

As I mentioned, we have two clumps of Wild strelitzia growing in our garden. Planted long ago by an unknown hand, the trees are now mature and stately. There are no sugarbirds in Harare, but the flowers on our trees do attract sunbirds. Lots of them.

The miombo double-collared sunbird that I photographed perched on the end of a strelitzia flower is just one of five species we’ve had visiting recently. That’s not bad for a suburban garden, and it’s thanks to the generous flowers of trees like Strelitzia nicolai.

-Ryan Truscott

We are delighted to hear again from one of our former regular contributors, Mary Toet. Mary is reporting on observations made on a visit to Makwe Cave area. This is particularly topical because last month we featured Ryan Trusscott’s very interesting story on mopane trees, and ‘mopane worms’ and their potential commercial value.

Moths have also been much in the news of late as “forgotten” night pollinators. In a very interesting documentary on the BBC it was brought to our attention that whilst there is huge concern about the general decline, worldwide, of bee populations very little is written about the decline or importance of moths as nighttime pollinators, the general feeling being, oh moths, they eat our jerseys, squash them. Let’s all become more aware of the importance of all our pollinators. Mary.

SLUG CATERPILLARS, MAKWE CAVE AREA.

A visit to the Makwe Cave area in late January provided an unexpected interest in the form of numerous green slug caterpillars, both small and large. These were everywhere under the Msasa trees and are a feature in Miombo woodland together with other interesting caterpillars and moths.

The moths have two generations a year and emerge in October and November. The colour varies between sexes and can be dull greens, greys yellowish or red. Followed by the second generation in February. Some of the caterpillars were probably ready to pupate but the diversity of size was indicative of different larval stages. Most were not feeding but moving in search of food.

The Msasa trees were very denuded of leaves and there was a gentle sound of falling rain which was the dropping of faeces. Some of the faecal material was in bundles of web and is referred to as frass.

The caterpillars belong to a family of tree moths of the family Limacodidae and three species of the genus Latoia commonly occurring in Africa are, Latoia latistriga, Latoia johannes and Latoia vivida. Cheryl Haxen took a caterpillar to an Entomologist who thought it might belong to the species L.urda (Duce). It would only be possible to tell once the immature form had bred out to the adult moth.

The slug moth caterpillars get their name because their legs are not apparent and they appear to move in a gliding sliding motion. On picking up a large specimen of about 30mm to examine the muscular contractions and fluid like motion in what were pseudolegs a painful sting was inflicted along the index finger from a line of iridescent blue spines. The spines break off causing irritation. Children are often tempted to play with the caterpillars and get “stung” by these spines find they are allergic to the poison and have to visit their doctor and require an antihistamine. The caterpillars are most colourful and fascinating because they flow along the branch and do not gallop, loop or move like other caterpillars. They are a great temptation to a young and enquiring mind.

The ‘vivida’ caterpillars are green and hence the name of the species. The sides of the body bear clusters of spines and resemble short tassels all around the edge of a rug. A pair of black dots with white borders are on each segment. Except on the third and eighth segment. The three thoracic segments have a bright red line along each side. The textbooks describe a light blue dorsal line of spines but the specimen under field investigation had two lateral lines of beautiful iridescent midnight blue spines. It was a painful encounter with the colourful little captive and I recommend discretion when examining them, there was not the same response to a pencil being run along the sides of the body. These blue spines were not readily visible.

Each spine is hollow and terminates in a short sharp point which can and does penetrate the skin if the caterpillar is roughly handled.

The caterpillars pupate by forming a rough hairy oval cocoon. The adult moths emerge in three weeks. Our arrival at the Makwe Cave area was at the time when the caterpillars would have been seeking a suitable twig on which to entwine their pupal case.

The moths of this genus are small about 30mm and are stubby with pale green forewings bearing a brown margin at the base. The hind wings are cream or light brown in colour. The adult moth has no proboscis and does not feed. Its function is reproduction and dispersal.

The eggs are laid like tiles on the underside of a leaf of the food plant. In some cases over wintering is done by the adult who hibernates and lays in early spring.

The slug moth should not to be confused with the Msasa moth.

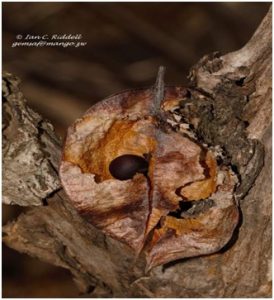

MSASA MOTH, PACHYMETA ROBUSTA.

Msasa moth caterpillar

The larva are a common sight in Brachystegia woodland on both Msasa and Mnondo and cluster together on the trunks of trees forming orange hairy mats. The caterpillar is large and spectacular and bears black spines. The caterpillars disperse at night to feed on the leaves.

The moth belongs to the family Lasiocampidae which includes the Lappet and Eggar moths. The female is a large stout moth with densely scaled wings. The forewings are narrow with brown and grey markings. A dark brown band crosses the forewings vertically. The forewings and thorax are greyish and the abdomen and hind wings are light brown. The adult stage does not feed.

The caterpillars spin large robust cocoons. The empty cocoons of some Lasiocampids are so large that they can contain small stones and be used as anklets for performing traditional dances in some parts of Africa. The genus Gonometa is recorded as being a particular nuisance because if cattle browse on bush in times of drought and swallow the cocoons the silk is not digested but unravels in the rumen clogging with the food and forming great lumps. If these obstructions are not removed surgically the animal will die.

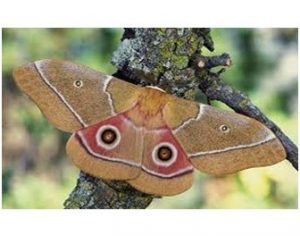

MOPANE WORMS. THE EMPEROR MOTH, GONIMBRASIA BELINA

These are not worms but caterpillars of a magnificent Emperor moth belonging to the family Saturniidae and are the biggest moths, many having wing spans in excess of 100 to 200mm. Most are recognizable by the large ringed eyespots in the hind wings. This is a protective mechanism because if displayed looks like a large animal to a would be predator The moth is very common and often found inside after dark when it is attracted to light.

The male moth has the feathered antennae.

The caterpillar known as the Mopane worm, Madora or Macimbi, feeds on Mopane, Carissa, Terminalia and other trees. The caterpillars are large and juicy and are about 55mm, and are highly nutritious. The caterpillar is banded in green and light green and has rings of small blackish spines.

The caterpillar is dried and sold in the markets where I have seen it piled on pieces of newspaper or in empty baby food “Purity” jars. About fifteen years ago Mopane worms were canned in small tins. The cooking process render the caterpillar smaller and brown and a bit soggy and not as resplendent as its former majestic glory. Gonimbrasia is the ambrosia of people both in the Northern Transvaal and Zimbabwe where it is considered a delicacy.

-Mary Toet

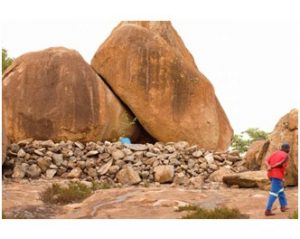

A SEARCH FOR THE BUSHVELD RED-BALLOON Erythrophysa transvaalensis

Erythrophysa transvaalensis Photo- Ian Riddell

Erythrophysa transvaalensis, the Bushveld Red-balloon (Sapindaceae) can quite justly be called as an ‘exciting find’, being classed as a rare tree in Zimbabwe.

Erythrophysa transvaalensis Photo- Ian Riddell

In this country, it is only known from a few localities west and south of Bulawayo where it grows on the rocky slopes of hills. On the 5th April 1998, the Matabeleland Branch headed out to the Gwanda area (Norma Hughes, Tree Life 219) to a ranch where it was seen in the early 1970s, but their search of the kopjies was in vain! A successful expedition to Malilangwe, the Peek’s property near Marula, had been mounted on 8th April 1996, and you can read about that in Tree Life 196. According to Kim Damstra’s ROOTNOTE in Tree Life No. 44, “Erythrophysa transvaalensis was first recognized in the country from a specimen discovered by Alec Dry on a Tree Society outing to the lone baobab near Khami Ruins. Bob Drummond went to see this exciting tree full of ‘red balloon’ fruit. It transpires that an earlier collection from Double Cross Ranch, Gwanda, had not been recognized.”

Collapsed walling near Khami. Photo- Ian Riddell

In January 2016, I was staying with a friend in Bulawayo and pursuant to Kim’s reference, and more importantly with some local knowledge to guide us, we met our driver at the museum and trundled out of town in his Landrover on a sunny Matabeleland morning. Many dusty twists and turns and tracks later, we parked near our destination and headed off, following cattle and people paths. On the way, we naturally had to stop and explore dry-stone walling, since that was one of our driver’s chief fields of interest, and eventually reached our target kopjies, clad in thick, dry bush.

Collapsed walling near Khami. Photo- Ian Riddell

Up and up we went and near the top of one, nestling with a burst of cheery greenery amongst the large granite boulders, was our reward, red balloons and all! These were only small trees or multi-stemmed shrubs but besides the pods, the most striking feature was the imparipinnate leaves with narrowly lanceolate leaflets and a winged rachis. We were also fortunate to find them in flower, attractive heads of pinky-red flowers with a burst of filaments.

As Coates Palgrave says, the seeds germinate readily and some I brought back to Harare did just that. However, we live in clay soils and I wasn’t certain they would do well in the garden so gave the seedlings away – to?? Can’t remember but it may have been to Bill Clarke, who has more appropriate granite habitat at his house; I hope they have survived!

-I.C. Riddell. Email: gemsaf@mango.zw

PARASITES OF INDIGENOUS TREES

The outing to Sanganayi Creek at Mazvikadei near Banket aroused interest in various topics. Very evident were the parasites on the Leguminosae which were Pilostyles aethiopica and Loranthus.

Seasonal change was evident and there was interest in the rain tree, Lonchocarpus capassa and the little spittle bug, Ptyelus grossus. Names have changed and Pilostyles ethiopica is now Berlinianche ethiopica. and the Loranthus we saw is now renamed Plicosepalus kalahariensis. It is a parasite of Acacia karroo and Acacia nilotica.

Having grown comfortable with Lonchocarpus capassa the name has been changed to Philenoptera violacea.

So much for name changes which in the Botanical World are as frequent as the street name changes in Harare.

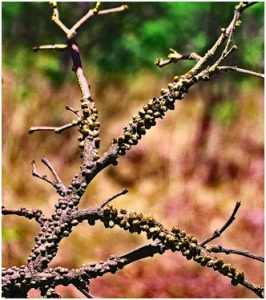

Berlinianche (Pilostyles)

Meg Coates Palgrave stimulated my interest in Berlinianche. It was at a walk in the Mukuvisi woodlands some years ago that my curiosity was aroused by this peculiar little plant.

Berlinianche pilostyles Mukuvisi Woodland Harare. Photo- Meg Coates Palgrave

Berlinianche (Pilostyles) Mukuvisi Woodland, Harare. Photo: Meg Coates Palgrave

The only part to be seen of the plant are little wooden cups about 2-3 mm in diameter on the branches of the Munondo. Dead twigs and whole branches are blackened and have the tiny little wooden cups along their length resembling spots, or a bad case of tree acne, a little reminiscent of the seed capsules of the common bottle brush. There are no sepals or petals or any leaves just numerous little horny cups. Entire branches were dead.

Berlinische is found 95% or more times on Julbernardia, Munondo, and only in Miombo Woodland. The parasite is almost a diagnostic feature of Julbernardia.

Meg was in the Herbarium and looking through a volume of FTEA (Flora of Tropical East Africa) and came across Rafflesiaceae and wondered if FZ (Flora Zambesiaca) had covered that family yet. And yes it has, and yes, the name is Berlinianche ethiopica (Welw.) Vattimo-Gill.

“It occurs in Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi and Tanzania, Gabon, Angola and Zaire. Although both Floras say parasitising species of Berlinia, Brachystegia, Isoberlinia and Julbernardia I stick to my contention that in Zimbabwe they are most often found on Julbernardia.

Do we all agree with Meg and are we all sure we know how to distinguish between Brachystegia and Julbernardia?

Meg quoting Visser (Johann Visser (1981) South African Parasitic Flowering Plants. ISBN 07021 12283 Juta) and adding her own observations writes;

“The South African representatives of this family (Rafflesiaceae) are all root parasites (of course they do not have Julbernardia there) whereas other genera may grow on, or rather within the stems of various trees. Considerable endophytic development of the parasite inside the host’s tissue is claimed to cause extensive invasion to the host and to precede the production of flowers – the only part of the parasite ever to protrude from the host. Being dioecious, male and female plants usually invade separate host individuals. That I can confirm. There was a lad from Switzerland here about 18 months ago and I took him and Tom Müller to the Mukuvisi and we were able to find both male and female

“FZ says the perianth is in two whorls of 5-6 segments, purple-red, more or less fleshy. It also says Herbarium specimens with male flowers appear to be far more common than those with female flowers.

I am sure that this is a true reflection but could well be coincidental.”

The purple-red colour in the perianth cup, the fused sepals and petals and is referred to as the perianth by Visser and Mabberly (Mabberly DJ (1997) The Plant- Book. A portable dictionary of vascular plants, Second Edition)

Having observed busy little black ants stamping all over the ‘cups’ it was queried if they might be the pollinators. Meg continued her argument.

“Although Visser mentions the strong probability of the genus Cytinus in South Africa being pollinated by ants I think it extremely unlikely that our Berlinianche is for two reasons. One the male and female flowers were fairly far apart. We would find a patch with one sex and then had to search for a patch of the other sex. I think it unlikely that ants would travel that distance. Secondly the bright red/pink is a colour that attracts birds”.

Has anyone observed birds visiting Berlianianche?

The FZ describes the fruit as a globose berry surrounded by persistent bracts and perianth segments. A very likely candidate for dispersal by birds. Lyn Mullin quoting Mabberley on the mistletoes (Viscaecae) writes the fruit of many parasitic plants is eaten by birds, but the viscid tissue on the seed prevents the seed from being swallowed, and the bird scrapes it off into bark crevices, etc. where it germinates.

A reference was made to mistletoe by Lyn Mullin with a reference from Roberts (1985 ed) Birds of Southern Africa, that Yellow-fronted Tinker Barbets have a particular preference for mistletoe fruit, but I am sure other fruit-eating birds will also take this fruit. The following sunbirds are recorded as feeding on the nectar of the mistletoes but I see nothing about them eating the fruit; Marico, Purple banded, Miombo. Double collared, Yellow bellied and White bellied.

On asking how destructive the parasite was Meg referred to the extensive invasion into the host but she had only noticed twigs and branches dead.

“It would be self defeating to kill the host plant, wouldn’t it?”

Lyn Mullin is of the same opinion but is referring to the families and genera that are hemiparasites. He writes “a hemiparasite is a parasitic plant that carries out photosynthesis, but also obtains food from its host. By definition, the haustorium of a parasitic plant does enter the vascular system of the host, but I suspect that only rarely will a host be so heavily parasitized that it will die. The parasite would naturally die with the host,

So I suspect that nature takes care of that by limiting the number of parasites on any one host – but I don’t know!”

On walking through the Mukuvisi I noticed trees with parasitized branches being cut down by tree cutters and the trees appeared dead. The death of the entire tree may not have been caused by the parasite but rather to opportunistic Homo sapiens looking for wood.

Perhaps if these trees that have been hacked down under the pretext of gathering dead wood are examined and found to coppice then the parasite has not totally destroyed the parent tree. Have readers any explanations or observations?

Plicosepalus kalachariensis (Loranthus)

At the visit to Sanganayi Creek this July the Loranthaceae were spectacular as they hung to advantage from branches of trees that had dropped their leaves during the cold winter period. The pretty pink, corals and reds looked like bunches of honey-suckle. The stems are referred to as dichasial. A dichasium is a type of inflorescence in which each branch of the inflorescence gives rise to two other branches. Mabberley describes the flowers as usually bisexual, usually regular, conspicuous and frequently red or yellow, insect or bird-pollinated, in dichasia sometimes resembling heads, racemes, umbels, etc.

A few weeks later when walking through Ewanrigg Botanical Garden the flowers of the Loranthaceae were not open but sticking out like little pink tubes with a dark purple cap. Ewanrigg is colder than Sanganayi Creek and the flowers were not at the same advanced stage. If insect pollinated, and certain species of butterfly are specific to species of Loranthus then these pollinators would not be active and may not have emerged from their pupal form.

Meg when asked about the pollinating mechanism quotes Johann Visser;

“Explosive anthesis has been developed to a high degree of perfection in this family. As the bud matures the corolla lobes become more turgid and strain outwards but are firmly held together at the margins. Then at the slightest touch the corolla lobes separate explosively outwards. Simultaneously the filaments inflex or recurve sharply thus releasing a cloud of pollen – in this way dusting the forehead of the pollinator. The style usually snaps to one side, apparently to prevent self- pollination, but also ensuring that the pollen from the forehead of the visitor is smeared onto the sticky stigma”

Although the caption to one of the pictures says: In their attempts to extract nectar sunbirds slit open the corolla tube of Tapinanthus rubromarginata – and so perhaps they are the pollinators. Roberts describes the sunbirds visiting the Loranthaceae.

Mabberley describes the family Loranthaceae as follows;

Photosynthetic hemiparasites, typically brittle shrublets on tree-branches, less often rrestial shrubs, lianes or even trees on host roots.

One or several haustorium (the organ of a parasitic plant that penetrates the host plant’s tissues and absorbs food and water from them) are at ends of epicortical roots (on the outside the bark of the host), plants are rarely like Cuscuta, Dodder, as their haustoria usually promote gall-like growth on the host. Stem often branching but without nodal constrictions. Leaves opposite or in whorls of three, simple, entire, rarely scale-like; stipules nil. Flowers usually bisexual, usually regular, conspicuous and frequently red or yellow, insect- or bird-pollinated.

Viscaceae was previously included under Loranthaceae.

The hemiparasites would be less likely to destroy the host unless present in great numbers. Berlinische without leaves and relying on the host for total nutrients could be more destructive.

Mabberley has 13 principal genera in Loranthaceae, of which Dendrophthoe (30 spp), Helixanthera (50 spp), Tapinanthus (250 spp), and Taxillus (60 spp) occur in the Old World tropics, including Africa.

Meg quoting Visser again:

Loranthaceae is represented in South Africa by 11 genera and 37 species. What used to be one genus (Loranthus) was recently reclassified into no less than 11 genera and he mentions Tapinanthus, the genus I am familiar with which I thought most of the parasites we usually see belong, and Septulina, Plicosepalus, Moquinella, and Erianthemum.

Perhaps we should be stimulated to look a little less at trees but to observe what is on trees and how trees interact with the rest of the ecological system. There is the old expression about not to seeing the wood for the trees and we tend to only see the trees.

-Mary Toet

UPDATE ON FAMILIES AND GENERA IN ZIMBABWE

Flora of Zimbabwe https://www.zimbabweflora.co.zw/speciesdata/family.php?family_id=125

Loranthaceae lists 14 genera with 31 species in Zimbabwe. Viscum is now placed in Santalaceae with 9 species in Zimbabwe. Also in Santalaceae is Osyris which is sometimes a hemiparasite as are some species of Thesium in the same family. Ximenia in Olacaceae is also thought to be a hemiparasite, perhaps with grass as a host.

Berlinianche (Pilostyles)

Berlinianche pilostyles Mukuvisi Woodland Harare. Photo- Meg Coates Palgrave

In 2012 Sidonie Bellot from the University of Munich visited Zimbabwe and did a study on this parasitic plant in the Mukuvisi Woodlands from 16 to 29 February. She stayed with Mark Hyde and he or I took her to, or collected her from, Mukuvisi Woodlands each day and so we had the opportunity to accompany her as well.

In her paper which included this study she named this parasite Pilostyles aethiopica Welw. and puts it into the family Apodanthaceae, in which there are three genera Apodanthes, Berlinianche and Pilostyles. Currently, most authorities maintain Berlinianche aethiopica (Welw.) Vattimo as the species with Pilostyles aethiopica Welw. as a synonym.

Sidonie studied 20 trees in five host tree patches of Julbernardia globiflora (Benth.) Troupin. The trees were 1,5 to 4 m tall with the parasite flowers, 12 of them carried only male parasite flowers, seven only female flowers, and one flowers of both sexes. The male flowers have a shiny, white hair crown at the top of their central column, whereas female flowers do not, making it possible to sex flowers by eye.

When the parasite was flowering on a flowering host, flowers of host and parasite never occurred on the same host stem.

The scent of male and female flowers was assayed by letting it accumulate in closed small glass vials. Floral scent could be perceived throughout the day, with no apparent change in intensity; female flowers produced scent before they opened. No difference in scent between male and female flowers was observed. The flower scent most likely consists of ethanol and related compounds in addition to fruity compounds as known from other fly-pollinated flowers.

Nectar presence was tested with diabetes testing strips that were inserted into flowers but its presence could not be verified because the quantities of nectar were too minute.

No insect eggs or larvae were found in any flower.

Observations were made during 10-minute periods between 0900 and 1700 hours on several days for a total of 36 observation periods. Notes were taken on flower sex, scent, number and kind of insect visitor, and visitor behavior. Visitors were also photographed, and captured and have been deposited in the zoological collections of Munich (Zoologische Staatsammlung München). Photographs and specimens were studied and identified by fly and ant specialists.

For the six most common visitors to both flower sexes, visitation frequency was quantified. Four fly species and two ant species were observed on both flower sexes and during more than one observation period.

The ant species Camponotus flavomarginatus Mayr, and Lepisiota capensis Mayr, (both Formicinae) are unlikely pollinators because they return to the nest between forays to different food sources.

The most common flies were Chrysomya chloropyga Wiedemann, copper-tailed blowfly, and Stomorhina sp. both belonging to the Calliphoridae. The flies alighted on branches near the flowers, which were too small for them to land on, approached them, and then probed the stamens or the base of the floral column with their proboscis, apparently looking for pollen grains or liquid. Their entire heads, including the upper part of the proboscis, came in contact with the anther ring or stigma.

Calliphoridae is the family of bluebottles, greenbottles and blowfies and according to Field Guide to Insects of South Africa (2004) by Mike Picker, Charles Griffiths & Alan Weaving, the adults particularly the females are usually attracted to decaying flesh etc., but the males are more likely to be found lapping nectar from flowers.

-Meg Coates Palgrave

TONY ALEGRIA CHAIRMAN