TREE LIFE

MAY 2020

Time of new hope, spring time in Brahystegia Woodland. Photo: Mark Hyde

TREES

I think that I shall never see

A poem as lovely as a tree.

A tree whose hungry mouth is pressed

Against the earth’s sweet-flowing breast;

A tree that looks at God all day,

And lifts her leafy arms to pray;

A tree that may in Summer wear

A nest of robins in her hair;

Upon whose bosom snow has lain;

Who intimately lives with rain.

Poems are made by fools like me

But only God can make a tree

Joyce Kilmer

This is going to be a different sort of Tree Life. We are living in different sort of times. We have no Coming Events and we have no Reports on Walks in the Gardens or Outings to lovely places. We have all been locked up protecting ourselves and others during this pestilence called Covid-19. We are not sure what the future holds, one thing is sure and it is that things are going to be different in the world.

We are all members of this great Society because of our love of or interest in or both of trees. I was married to a botanist/entomologist for 50 years and our work was in the bush all over this beautiful country of ours. I also worked for Dr. Joe Ritchken for 25 years and his great interest in and love of trees involved him in the early stages of the development of the National Botanic Garden, coming on bush trips with us, collecting and then germinating seed for his new found best friend Tom Muller and Tom’s emerging Garden. Joe waxed lyrical when he spoke about trees and Tom’s Garden and I probably had Joe and Tom in mind when I wrote the following for Tom Muller’s 80th birthday party, which, you will remember, we celebrated in the Garden, this amazing National Botanic Garden which Tom had created.

“It is a wonderful thing if you can see a tree from your window, for the mind is uplifted and enriched by living close to trees. You can be drawn to a certain tree in the same way that you can be conscious of affinity with a person. You can make a friend of a tree, for it is something more than wood and bark and sap. It is an expression of beauty, strength and grace, and it is built up by the same force that holds your own body together, the mysterious power of God at work in His creations. We are gathered here because we all have this love of trees in common and have just had a lovely walk with Tom in his garden – how much pleasure have these gardens given to us all.”

We all have this love of the bush, its trees, and all that goes with it, in common and hopefully, this pandemic and “different time” will not alter anything and soon we will be able to be out botanizing with all the wonderful camaraderie that goes with it also, and with even more enthusiasm. In the meantime, keep safe.

Mary Lovemore, Editor

The desert date tree, hero of the Sahel Balanites aegyptiaca (simple thorn torchwood)

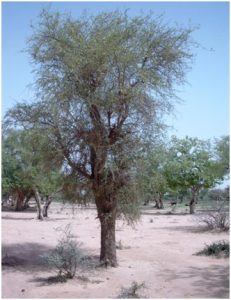

Balanites aegyptiaca. Photo Wikipedia

Even in the most arid conditions the desert date has much to offer; fruit, wood, oil, leaves and flowers. It is a species which deserves attention from researchers.

After the droughts of the nineteen seventies and eighties, the Sahel looked like a grave yard for dead trees. The shea, acacia and locust bean had all succumbed to lack of water. All but one, Balanites aegyptiaca points out Hubert Gillet, Assistant Director of the Paris Natural History Museum, “It can live longer than other desert tree, more than 100 years, and it is the most resistant to drought”.

It has adapted to adversity.

Nature has given the desert date a whole armoury of weapons against the conditions it has to endure. The species, which rarely exceeds 10 meters in height, is widespread throughout the Sahel. Its leaves are thick and tough with a glossy coating that provides protection from the dry air. Its double root system acts vertically and horizontally, finding water up to seven meters below the surface and within a radius of up to 20 meters from the trunk. This root system also helps the tree to resist the sandstorm damage that can uproot other species. Should the leaves fall, photosynthesis continues through the branches and spines and is enough to ensure the tree’s survival. And, as a further example of its amazing adaptability, a coating of sand surrounds each root, maintaining an insulation layer of air which helps to even out temperature fluctuations and reduce evaporation. From the top of the tree to its roots, the desert date is well adapted to survive the extreme conditions of the desert.

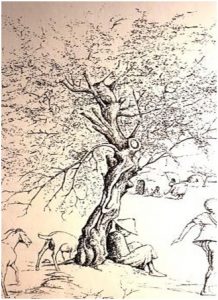

Family life around a Balanites aegyptiaca. line drawing from Spore Vol. 50

The tree is thought by some to be the home of spirits, and sacrifices may be offered in its shade. However, there are many other reasons why the desert date has long been revered by local people. Like Acacia albida, the desert date comes into leaf before the beginning of the rainy season, turning green in March or April. The leaves provide valuable fodder and are a godsend for the livestock, which have little else to eat at the end of the dry season. The tree’s spines make it essential that the herdsmen take the precaution of collecting the forage themselves before giving it to the animals. But these spines have a use as pions, for surgical sutures or as muzzles. The desert date has other useful attributes, the wood is hard enough to be used for mortars, tool handles and even roof frames, since it is also resistant to damage by termites.

The desert date is also valued for its fruits. These used to be referred to as “slave dates” because they are of poorer quality than true dates, but they now enjoy more respect, a reflection of the current hardship of life in the region. According to Marie Jose Tabiana a research scientist at the Centre National de Recherches Scientifiques (CNRS) shepherds and children suck the raw fruit, but it can also be cooked in order to extract the sugar which can be added to porridge or used for making sweetmeats. There are many different local recipes.

Another use has been recorded by Paul Creac’h, a pharmacist who worked for the colonial army in the 1930’s. In the hungry season or during food shortages, when the store of millet has been exhausted, women mixed the date fruit pulp in a mortar with a few handfuls of millet. You can still often see this being done today. Creac’h also notes the medicinal qualities of the leaves and bark, which were used as a disinfectant or treatment for rheumatism or jaundice. Even today, sucking desert dates is strongly recommended for anyone suffering from a chill.

According to Marie Jose Tubiana “it is the qualities of the kernel which is most important.”. This has an oil content of 40-60% and is a richer source of protein than groundnuts, cotton seed or sunflower. The oil which is difficult to extract, has to compete today with groundnut or cottonseed oil, but it is highly prized by certain tribes which appreciate the value of its nutritional and medicinal qualities.

Scientists have been emphasizing the importance of Balanites for a long time. Researchers at the Centre National de Recherches Scientifiques (CNRS) have now decided to establish a network in order to share all the available information and to publish a survey of current knowledge so that the tree’s potential becomes better known and can be taken into account in reforestation and development schemes.

-Taken from Spore Vol. 50

We recorded Balanites aegyptiaca on our last visit to Hippo Pools. Ed.

We Need to change how we grow our food

As COVID-19 spreads worldwide, we’ve become attuned to those on the front lines: Doctors and healthcare workers, yes, but also those who feed us. If we didn’t get it already, this global crisis is a wake-up call for how our collective fate is tied to the way we relate to nature, use the land, and treat farmers and workers who grow, process, and distribute our food.

Unfortunately, in the last half-century, both public and private investments in industrial food systems that exploit people and undermine the natural systems on which food security depends have ramped up.

Worldwide, industrial agriculture drives 80 percent of deforestation. On nearly every continent, land grabs by agribusiness have pushed small farmers onto increasingly marginal land and indigenous communities off ecosystems they’ve long stewarded. These dynamics have brought wild animal populations, natural hosts for pathogens, into closer contact with humans.

Threatened unspoilt forests.

Scientists have long warned it would only be a matter of time before those pathogens found new hosts — us. Indeed, damning evidence from evolutionary biologists and epidemiologists suggests that the industrial food system has helped create the structural conditions for this outbreak, and for others to follow in its wake. This crisis is a powerful reminder that our industrial food system puts us all at risk.

But there is another way. As funders investing in food systems that promote biodiversity, farmer well-being, and health, we’ve witnessed incredible innovations in the past few decades that give us hope amid the crisis. Earlier this year, we helped convene innovators — scientists, farmers, policymakers, funders, and advocates from five continents — sharing strategies for food system resilience and the policies needed to defend it.

We heard from indigenous Peruvian potato farmers, West African women rice farmers, and indigenous livestock breeders from Kyrgyzstan whose work is all rooted in what is known as “agroecology” — the science, on-farm practices, and social movements that support food systems working with nature instead of fighting against it with synthetic, external inputs. Guided by principles of diversity, regeneration, and localization, agroecology combines indigenous and traditional agriculture with modern science, boosting animal and crop health for maximum nutritional benefit and ecosystem restoration.

At that gathering in southern India, we heard firsthand accounts of the impact of our industrial food system even before this current pandemic: Reliance on chemical inputs and fossil fuels — for pesticides, fertilizer, packaging, and transportation — destroys biodiversity, plunges farmers into debt, and contributes to the climate crisis.

We heard about how a myopic focus on commodity crops has resulted in unhealthy diets responsible for the surge in diet-related illnesses worldwide and how industrial animal agriculture operations breed disease and drive massive water and air pollution. We also heard how such a dependence on commodities, bought and sold on a volatile global market, creates a shaky foundation for food security and breaks the connection between eaters and food producers.

But we also heard solutions. In Kyrgyzstan, peacebuilding programs are working with herders and geneticists to revive the disappearing gene pool of two aboriginal livestock breeds — the Kyrgyz horse and the Buryat cow — to help restore Central Asia’s nomadic pastoralism and pasture ecosystems. By focusing on preserving this genetic diversity, these breeders ensure that native livestock thrives — livestock that is resilient to the region’s harsh climate. In contrast, animals bred exclusively for productivity crammed into factory farms increases the risk of illnesses and dangerous pathogens.

In Burkina Faso, Groundswell International is working with farmers’ movements using agroforestry, mixed cropping, rainwater harvesting, and composting to gain incredible results despite the water scarcity near the encroaching Sahara desert. With these practices, they’ve reclaimed abandoned land for farming and obtained up to 130 percent yield increases of millet and sorghum, while regreening the landscape and adapting to climate change. In agroecological systems like these, the use of diverse and native species bridges wild and cultivated areas, helping to manage pests while also providing vital pollinators with continuous habitat.

In southern India, grassroots farmer networks like the Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha and village-level women’s self-help organizations have been advocating for years for a shift to natural farming practices to prevent dependency on chemical inputs, farmer debt, and spiraling farmer suicides. Policymakers listened. Today, the Andhra Pradesh state government supports more than half a million farmers to adopt agroecological practices in a massive public program called Community Managed Natural Farming.

In Ecuador, the civil society-led Agroecology Collective collaborates with municipal governments in a campaign for healthy, safe, and locally grown food through a network of farmers markets and direct-to-consumer food programs, known as CSAs or community-supported agriculture. Shortening the supply chain between those producing food and those consuming it, as it’s being done in Ecuador, is essential to weather crises.

From Malaysia to Mozambique to Mississippi, we heard about the myriad benefits of solutions grounded in those core principles of agroecology: diversity, regeneration, and localization. These benefits have inspired not just foundations like ours to invest in agroecology; they have inspired burgeoning public investments and acknowledgment of the value of these practices. In 2014, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization endorsed agroecology as a key pillar of the food and agriculture system we need. This year, the Convention on Biological Diversity will consider including agroecological solutions in its biodiversity framework. And ministries of environment and agriculture around the world are increasing investments in agroecology, many as pillars of post-Paris Agreement climate mitigation and adaptation action plans.

COVID-19 has reminded us we cannot take our interrelation for granted — with each other or with nature. We must rethink an industrial food system that ruptures these vital relationships and step up our efforts to support practices that restore and sustain them. By ramping up private and public investment for agroecology now; we can feed the world and strengthen our resilience against this crisis — and the ones yet to come.

Anna Lappé is an author and advisor to funders supporting food system transformation. Daniel Moss is the Executive Director of the Agroecology Fund.

By Anna Lappé and Daniel Moss

We publish this interesting article with kind permission of “Food Matters” Ed

This month we continue down memory lane with Jim and Ann, I wonder how Jim would cope with sleeping on the ground 30 years down the line. Ed

A CANOE TRIP continued

A most satisfactory start for all of us and now it was time to set up camp, wash in crocodile infested waters and then have a well earned whisky and Zambezi water. The washing created much mirth and what with naked matrons bathing by the stream and the absence of any other facilities it was a good thing we were all friends of very long standing!! Fortunately we had all made certain that plenty of Scotland’s finest was available and sipping a glass of Chivas Regal on the banks of the Zambezi seemed to us to be a fine example of savoir faire. After an excellent supper of mince, rice and veg cooked by Titch and Anthony and after some of Charlotte’s jokes followed by one or two unrepeatable stories from Ben and a few golden oldies from me, off to bed!!

When they were young and beautiful

However, this did not prepare us well for the rigours of the night and I found the hard ground not at all conducive to a good sleep. Police reserve duty all those years ago made me think that I could sleep anywhere, but not any more!

However, the morning brought relief and an early start and a glorious sunrise as we set off on our second day into the trip. The river was almost iridescent it was so calm. A Fish Eagle gave his mournful cry and we were accompanied for a while by a Sacred Ibis singing his way down the river. Game is sparse as they have all gone back into well watered areas after the good rains. We saw a couple of buffalo, old dagga boys, a few impala and crocs and plenty of hippo.

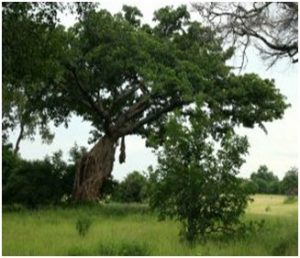

Ficus bussei. Photo Bart Wursten.-Source Flora of Zimbabwe

The bird life is magnificent and April is the best time to be on the river if you want to see birds. We compiled a list at the end of the trip with the help of our guides, and had a final count of 92. Along the banks we saw many white crowned plovers, blacksmith’s plovers with their strident call, the water dikkop, the Kariba battery bird, so named as its call sounds as if it is running down. Pied wagtails and pied Kingfishers also frequent the banks. In the reeds we saw the red bishop bird, blue cheeked bee eaters, masked and speckled weavers busy attending to their intricate nests. White winged terns were much in evidence some in their breeding plumage. Egyptian Geese abound as do the cattle egret and greater egret.

We pulled into the bank for breakfast after a couple of hours paddling and really appreciated the scrambled eggs, bacon, tomatoes and fried bread cooked up by Anthony and Titch. We needed our strength for the next stretch. We canoed across the river and went some way close to the Zambian bank, which had some beautiful thick bush including some beautiful specimens of Ficus bussei. The river seemed incredibly wide when we crossed to the opposite bank and we marvelled at the volume of water, at times we had the sensation of going down hill. Lunch the second day was under an Acacia albida and Natal mahogany growing so close they were almost one. There was a lovely herd of impala grazing nearby. We had some keen fishermen in the group and Keith and Dave had a rod in the water at every stop. They had moderate success and caught the odd tiger and a couple of small bream, they had some good runs later when we were at Rukomechi, but the star fisherman of the trip was Cathy who I think, caught the biggest tiger and the most fish.

Jim and Ann Sinclair – to be continued

New non-GMO bred banana

After decades of pro-GMO hype telling us that only GM will save the banana from going extinct due to attack from black Sigatoka disease, non-GMO breeding has produced a variety that is resistant to the fungus.

The new variety of banana can be produced using organic and agroecological production methods and is set to become commercially available in France, according to an article in FoodNavigator.

The banana, called Pointe d’Or, was developed by the banana industry in Guadeloupe and Martinique in collaboration with research organisations. It is the product of an alliance launched by the French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development,(CIRAD).

The alliance says that new varieties and production systems must be developed worldwide to protect the global supply of bananas, which is threatened by diseases.

The problem, as usual, lies in the lack of genetic diversity in commercial banana growing. Just one variety is grown for international export markets – the Cavendish. The variety is not only bland tasting but is now prone to diseases in many regions.

We publish this article with permission from Food Matters. Ed.

Tree Society of Zimbabwe website update April 2020

During the last month, 21st March to 21st April, there have been 773 hits with the peak day being on 6th April with 47 hits. What I find amazing is where these hits are coming from and besides Zimbabwe with 363 hits, where we expect the most interest to come from, the USA is next with 118 hits followed by South Africa 94, United Kingdom 56, Australia 23, Canada 7, Nigeria 7, Botswana 6, New Zealand 6 and Austria 5. These were the top ten countries accounting for 690 hits, the remaining 83 hits would be shared by anything up to another 40 countries.

Of interest are the most visited pages: The Tree Society of Zimbabwe home page, Tree Nurseries, Tree Life no. 95, Tree Life no. 439, Newsletters page, Tree Life no. 426, Gallery and Herbal Remedies. We now have individual Tree Lifes being looked at which are in the top ten!

We would like to add another gallery to the website dedicated to spectacular trees and for this to happen we need your help! First question is, what is a spectacular tree? This was debated and I feel what constitutes a spectacular tree is not just size. After all, how do you measure size? Tall trees such as many eucalypts are not great, they are just kind of normal. So, is it height, girth or mass that makes a tree stand out and look spectacular? Let’s face it, a Msasa tree with the height of an average sized eucalypt would be quite a site! What are your thoughts? I would like to hear from you soonest so we can include your thoughts in the next Tree Life. Only your response will be used – not you name unless you make it clear that you want your name to be used.

-Tony Alegria

The following little story, which I believe sums up the spirit of self giving which is so prevalent at this time of Covid-19, was posted on Facebook by a very regular contributor to our Tree Society Facebook page, Adam Ewing, thank you Adam for all your contributions. Ed

‘The Giving Tree’ by Madison Brewington

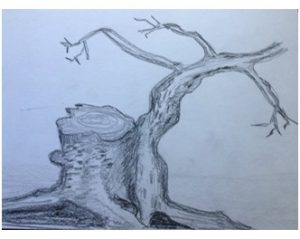

Sketch by Ann Sinclair

And after a long time the boy came back again.

“I am sorry, Boy,” said the tree, “but I have nothing left to give you-

My apples are gone.”

“My teeth are too weak for apples,” said the boy.

“My branches are gone,” said the tree.

“You cannot swing on them-”

“I am too old to swing on branches,” said the boy.

“My trunk is gone,” said the tree.

“You cannot climb-”

“I am too tired to climb,” said the boy.

“I am sorry,” sighed the tree.

“I wish that I could give you something… but I have nothing left. I am an old stump. I am sorry…”

“I don’t need very much now,” said the boy, “just a quiet place to sit and rest. I am very tired.”

“Well,” said the tree, straightening herself up as much as she could,

“well, an old stump is a good for sitting and resting. Come, Boy, sit down. Sit down and rest.”

And the boy did.

And the tree was happy.

TONY ALEGRIA – CHAIRMAN