TREE LIFE

October 2019

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Saturday 05 October 2019. 08:30-10:00 NATIONAL BOTANIC GARDEN WALK Saturday morning. We will look at anything interesting! There should be quite a lot coming into flower, it is a lovely time of the year in the garden. Join us for a 1.5 hour walk, we will start at 08:30am from the usual place – the car park. Bring a friend and enjoy time in this peaceful garden.

Date: 20 October 2019. Time: 09:30-12:00. Location: Botanic Gardens, Harare. Because of the fuel shortages and other constraints we are going to meet in the Botanic Garden again. We meet at the car park, as usual, but we will drive around to a totally different area and look at different trees. Bring your refreshments and folding chair as you would normally do for a Sunday morning outing. You are welcome to have a picnic lunch in the garden after the walk. Non members are very welcome to join us and get to know this facility in the city precincts and also familiarize yourselves with some of our indigenous trees.

BOTANIC GARDEN WALK: 7 SEPTEMBER 2019

A group of 7 hardy people met in the car park on a chilly grey morning with a bitter wind. Despite the weather, Spring was in the air with many trees beginning to show flowers and/or new leaves. Tony Alegria was the leader.

We first looked at some planted trees near the car park.

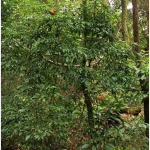

Syzygium jambos (Myrtaceae). Photo: Mark Hyde

In the shade of other trees was a specimen of the Rose apple, Syzygium jambos (Myrtaceae). This Asian species has dark green narrowly lanceolate leaves, relatively large flowers which are a mass of white stamens and large edible fruit. This is a commonly grown species in Zimbabwe and has been recorded as an escapee in some places. Of interest was the presence of an inflorescence-like gall; these are often seen on Syzygium guineense but were new to me on this species.

Eucalyptus torelliana Photo: Mark Hyde

Nearby was a fine specimen of Eucalyptus torelliana (also Myrtaceae), the Cadaga. Tony showed us the numerous squat barrel shaped capsules which were lying under the tree. The bark is rough and brown below, but above about 3 m or so, is a smooth greyish-green colour. Both the broader green juvenile leaves and the narrower greyer adult leaves were present. It occurs in the coastal foothills and adjacent ranges of northern Queensland in the vicinity of Cairns and it is one of the few species of Eucalyptus which grows in tropical rainforest. It is a frequently planted species in Harare.

From there we walked over to the colony of the Camel thorn Acacia erioloba (Fabaceae – Mimosoideae). This Kalahari sand species was just coming into flower. Beneath the trees were many of the distinctive broad, grey pods. Nearby was a flowering msasa (Fabaceae – Caesalpinioideae) and we stopped to examine the flowers and enjoy their pleasant fragrance. The structure of these is not obvious. Enclosing the flower are two very noticeable brownish obovate or circular bracteoles (second-order bracts). Next, there are up to 4 sepals which are linear-lanceolate, often poorly developed and sometimes absent altogether. There are no petals but the 10 stamens are quite prominent and in addition there is a hairy ovary bearing a stigma and style.

The next flowering species examined was the Mouse-eared combretum, Combretum hereroense (Combretaceae). Species of combretum are often named as bushwillows. I understand that this is because of their similarity when in flower to species of Salix (willows).

A specimen of Searsia (Rhus) lancea (Anacardiaceae), known as the Willow rhus, the Willow crowberry or Karee, was nearby. This winter-flowering species had more or less finished flowering and was in fruit. This is distinguished by its 3-foliolate leaves in which the leaflets are exceptionally long and narrow. Of interest here was the fact that the leaves had a slightly winged rhachis, a characteristic I hadn’t seen before.

Haplocoelum foliolosum (Sapindaceae), the Northern galla-plum. Photo: Mark Hyde

Two more trees in flower were the Live-long (Lannea discolor – Anacardiaceae) and the Worm-cure albizia, Albizia anthelmintica, (Fabaceae – Mimosoideae). The Lannea has small spikes of yellowish flowers which emerge from the apex of the fat (ET-finger) branches, usually when the tree is completely leafless as was the case here. The Albizia has numerous powder-puff inflorescences borne along the branches and consisting of many white stamens.

In a patch of dark woodland, I came across some specimens of Haplocoelum foliolosum (Sapindaceae), the Northern galla-plum. I think most people had gone ahead at this stage so I don’t think it was seen by many people. This is a rather local species in Zimbabwe; in fact, we only have one record on our website, from 1997! However, we have seen it in the Chegutu/ Kadoma areas on other occasions. It is a shrub or small tree with quite distinctive paripinnate leaves and 9-11 pairs of small broad leaflets. These particular specimens were in autumnal colouration, strongly dark reddish-brown.

This is only a selection of the species we saw. As always, no matter the time of the year, the Botanic Garden is a regular and reliable source of botanical interest.

-Mark Hyde “Age cannot wither, nor custom stale her infinite variety”.

What a beautiful description of our National Botanic Garden – Mary)

Saturday 28th September 2:30 at Mark and Linda Hyde’s home,

On Saturday afternoon 28th September, eight Tree Society members met at the home of Mark and Linda Hyde. (Mark, Meg, Jan, Julienne, Anne S, Mabube Sanjary, Tony and Dawn and Linda joined us as we first went round the Hyde’s garden). Having had a really cold snap, the weather was perfect. Mark had prepared a list of about 100 trees and shrubs that could be found in his garden, nearby gardens or lining the roads. This impressive list had scientific and common names and was very useful.

We first looked at the rather magnificent Erythrina crista-galli (Cockspur coral-tree) which comes from Central America. The orange flowers looked like the Erythrinas we get here but were much larger. It took us quite a long time to move out of Mark’s garden as there was quite a lot to see – Cascabela thevetia (yellow oleander), Croton megalocarpus (the popular shade tree Kenya croton), Cupressus which had an epiphyte growing on it, Ficus macrophylla (Moreton bay fig from Eastern Australia with its dark brown underside to the leaves), Ficus pumila (Tickey-creeper growing on a boundary wall), Rauvolfia caffra (quinine tree which was in flower) and the Schefflera actinophylla (Queensland umbrella tree from Australia).

On the pavement outside Mark’s garden was a large Harpephyllum caffrum (Wild plum) with its small red edible fruit which the school children enjoy. Across the road was an Acacia angustissima (Fern acacia) which Mark explained had no thorns. Someone touched the tree and there was a loud ‘Ow’! Mark conceded that maybe it did have thorns!

Mark explained that de Villiers Road, which we were turning right into, was Ceiba Road (not Cyber and nothing to do with computers!) as it was lined with Ceiba insignis (Yachan with its white flowers) and Ceiba speciosa (Brazil kapok or Silk floss tree with pink fluffy flowers). Further along there were examples of Acacia tortilis (Umbrella thorn) and Acacia xanthophloea (Fever tree) and Moringa oleifera (Horse-radish tree). The large trees shading the parking area for Hellenic school were Acacia sieberiana (Paperback acacia)

On Mark’s regular walks in the area, he takes his phone with him. He can take photos for records and identification and it also gives him a GPS reading. Sometimes passers-by will see him secretly talking into his phone and also peeping into other people’s gardens! Some of the trees and plants we saw in the nearby gardens and along the roads were:- Ficus benjamina (weeping fig), Acacia galpinii (Monkey thorn), Agave vivipara (Caribbean agave, Duranta erecta (Golden dew drops – clipped into a hedge), Faidherbia albida (apple ring), Homalanthus populifolius (Queensland poplar), Lagerstroemia indica (Pride of India), Lantana camara, Ligustrum lucidum (Glossy privet), Melaleuca bracteata (Johannesburg gold), Macadamia, Prunus cerasoides (Himalayan flowering cherry), Schinus terebinthifolius (Brazilian pepper tree), Stenocarpus sinuatus (Firewheel tree), Syzygium jambos (Rose apple), Peach tree, Syringa tree in full flower, Monkey puzzle tree and Tea tree. It was interesting to learn some of the scientific names of common exotics.

When we returned to the Hyde’s property, Linda had prepared a delicious tea for us – tea, coffee, cool drinks, cakes, biscuits, sandwiches and scrumptious strawberries dipped in chocolate!

A big thank you to Mark and Linda for a most enjoyable and informative afternoon!

-Dawn Siemers

Tree of the Month Ziziphus mauritiana

Ziziphus mauritiana growing beside the Arundel School Road, Mount Pleasant Photo: Ryan Truscott

Our tree of the month has neither flowers nor fruit. At least, not if it grows in Harare. It is Ziziphus mauritiana, or the Chinese apple.

Despite its lack of breeding capacity, it is becoming a common tree along roadsides in the capital. My interest in the tree was piqued a few months ago when I first noticed a shapely specimen growing along The Chase, in northern Harare. I mistook it for Ziziphus mucronata, the Buffalo-thorn, and was secretly impressed that someone had thought to plant an indigenous street tree.

I made a similar mistake on my morning walk. There are several along my route, with deeply-grooved bark and the typical Ziziphus leaves, with their three veins from the base.

Only when I picked a leaf and compared it to the Z. mucronata in my garden did I notice the difference.

Asymmetrical leaf base of Z. mucronata (left) and symmetrical base of Z. Mauritiana Photo: Ryan Truscott

The leaf of Z. mauritiana is greyish-white underneath, and the base is symmetrical. The Z. mucronata leaf has an asymmetrical base, and its underside is green.

On further inquiry, I learnt that the Chinese apple is an unwelcome invader here, as it is in other parts of the world, like Queensland in Australia. In this region it was introduced from the Middle East or India many generations ago.

Z.mauritiana-bark. Photo: Ryan Truscott

With my eyes now primed, I began to notice more and more of the trees in Harare. In some places, like on the Glen Lorne section of Enterprise Road, saplings are growing up thickly.

The question is: how is that possible without seeds? Well, it’s starting to become clearer.

Z. mauritiana, with the three veins from the base, typical to the genus Photo: Ryan Truscott

Researchers from the University of Zimbabwe’s Department of Geography and Environmental Science collected data along the Guruve and Centenary roads that connect the Zambezi Valley with the highveld.

In the lower altitude of the valley, Z. mauritiana does produce flowers and fruit. The researchers found that the plant is being spread by truck drivers who eat the fruit and chuck the seeds out the window, aiding what scientists call a “human-induced species invasion”.

I daresay the treads of cars also pick up the seeds from the surface of the highways, and scatter them along suburban roads in Harare. Our vehicles are playing the part that animal hides and hooves do in the wild for some plant species.

Just how worried should we be about this invasion?

The UZ researchers, who published their findings recently in the African Journal of Ecology, noted that invasive species play a major role in biodiversity loss. But, they point out, Z. mauritiana may simply be colonising vacant niches left by us through the removal of native trees and shrubs along roadsides.

Despite being an exotic, the tree has long been rooted in local society. It has an indigenous name: Musau and a notorious reputation for being a key ingredient in kachasu – that potent illicit brew imbibed by hardcore drinkers, sometimes with fatal effects.

Removing the tree is hard. It’s said to thrive on mutilation, and its roots go deep, rendering mechanical extraction useless. Experts suggest trimming the tree, and treating the stump with chemicals.

All sounds like a headache worthy of a kachasu hangover.

-Ryan Truscott

Tree Society of Zimbabwe website update.

Since we went live on 9th November 2018 we have had a total of 3426 hits as on 26th September 2019 at 10:00 am. The top ten countries using the website are: Zimbabwe 1771 hits; United States 518; South Africa 220; United Kingdom 191; India 100; Australia 76; China 41; Canada 28; Zambia 26 and Kenya 25 which account for a total of 2996. This means that the remaining 430 hits come from many other countries.

We went online with not too much content, but we have been adding Tree Lifes and articles on a fairly regular basis and have probably more than trebled the content since then. Also added were two new menu items – FAQ and Odds & Sodds. We ask the question under FAQ and more often than not have a page under Odds & Sodds to answer the question. This is interesting information which doesn’t logically fit under the other menu options. You will also noticed that the number of topics under some of the menu options have also increased a fair amount.

Mary Lovemore retyped past copies of old Tree Lifes that were printed on newsprint. These newsletters had yellowed with age and thus scanning them with Optical Character Recognition software was not an option. All newsletters that were emailed were much easier to handle as you could simply copy and paste them. Having said that, it still takes a lot of effort and time to get the Newsletters onto the website and photos have been added to the Tree Lifes even when there were none before making the whole exercise rather challenging. Mary has been an absolute star and has put more that 90% of all the Tree Lifes onto the website. Mary is passionate about the website and keeps finding articles of interest within past Tree Lifes to add to the pleasure of surfing our website.

In the last month we have had a total of 541 hits with the top ten countries being: Zimbabwe 246 hits; United States 80; South Africa 50; United Kingdom 34; India 16; Australia 15; Namibia 8; Botswana 6; Pakistan 6 and Canada 5. Devices accessing the website are: Desktop 54%; Mobile 39% and Tablet 7% with the two most popular pages being: Tree Nurseries and White Jacarandas.

Whilst on White Jacarandas, I would like to know if there are any other White Jacarandas that can be seen from the road to add to the list. Surely there must be more of them in Harare and in all the other towns and cities in Zimbabwe!

Have a good look at the Website and let’s hear from you if you have any ideas on how to improve the website or have a topic of interest to add. You can contact us via the website.

-Tony Alegria

NATURAL DYES FROM TREES – SUNDAY 3 OCTOBER, 1993

Taken from Tree Life 165, November 1993

We arrived at Mabukuweni just after 10.30 am to find June Davies already installed with her boxes of dyed wool samples and an intriguing hay-box, cardboard covered with tin foil, shiny side out, and insulated within with discarded wool. It was complete with dye-pot, glass and a tin-foil covered hinged lid for directing the sun’s rays on to the glass. This she uses to heat her mordants and dyes and so save on the ever-rising costs of electricity.

The natural wool yarn comes from her own sheep and she holds week-end courses on wool preparation, spinning and weaving.

Wool is very easy to dye with natural dyes, but because it is a sensitive fibre, care must be taken with the cleaning and dyeing process. Mordants are used to make the wool more receptive to the dyes and also to improve colour fastness. By adding a different mordant to the same dye-plant you can get different shades and colours which always blend harmoniously together – very subtle differences which enhance June’s wall-hangings.

Her most used mordant is ALUM but other chemicals are COPPER SULPHATE, POTASSIUM DICHROMATE, FERROUS SULPHATE, CREAM of TARTAR and BICARBONATE of SODA. Use of these various chemicals can sadden (deepen) the colour. You dissolve the chemical in a little hot water and put this into the container for mordanting. Fill the container with cold water and place into it the dampened wool skeins. Heat the water to boiling point and keep at this temperature for two or three hours. Allow to cool before removing wool. Before the actual dyeing process can begin the collected dye-plant material must be cut up or crushed and then soaked in water for two or three days, brought to the boil and boiled from one to six hours depending on the strength of the material – roots only need to be simmered.

Wool skeins must be wet before adding to the dye-bath. Add sufficient cold water to cover and bring dye-bath to the boil for one or two hours. Keep stirring and testing till desired shade is reached.

Let container cool as this strengthens the colour and then rinse skeins thoroughly in cold water.

June uses the 2 – 1 ratio as a rule and she also uses the process of over-dyeing, that is mixing her dyes to achieve the desired colour.

Dichrostachys cinerea. Photo: Flora of Zimbabwe

She then showed us samples of dyed wools – three or four variations in the same dye – bath using different mordants and the differences and blends were quite amazing and always in harmony.

Rhus lancea leaves produce yellow to khaki shades; Croton gratissimus rich earthy colours; Dichrostachys cinerea a yellow; Berchemia discolor varying shades of purple, pink, orange and brown. June was thrilled when the pods of Acacia karroo gave her the nearest to black she has yet achieved, but she was disappointed with her results in using

Marula, Sclerocarya birrea bark. Her dyes using Indogofera erecta were sometimes brilliant and oft times indifferent – never consistent in achieving those elusive blues and June is still wanting help in getting a true rose madder. Trees can contain the dyestuff in the leaves, bark, roots, pods, fruit, seeds or flowers, the latter strangely enough not often although their colours are bright. Care should be taken in the collection of these so as to preserve and never to destroy.

Lichens and moss need no mordant. June collects the former from trees, never from rocks because of their slow growth rate. These produce orange, brown, yellow and green shades.

Of the herbs blackjack, Bidens pilosa and Khalki bush, Tagetes minuta produce bright orange, yellow and green and the Amaranthus species give a greenish range. June has even collected and used the cochineal insects from Prickly Pears, Opuntia ficus indica, in her search for pinks.

Thank you June for a well prepared and informative talk giving us yet another outlet in our study of trees.

-Thora Hartley

INSECT-PLANT RELATIONSHIPS

TREE LIFE No.153 (November 1992) contained a very interesting article by Rob Paré on the close relationships between insects and plants. This is worth reproducing in full:

Virtually every species of butterfly or moth, worldwide, depends on the leaves of one plant or another as food for its developing larvae. A few species utilize either flowers, fruits, or seeds, some bore into the stems, some exist on various algae, and some are even carnivorous – but that is a subject all on its own.

There is virtually no plant anywhere that doesn’t bear evidence of having had part of it eaten by some insect or other. There are many recorded relationships between plants and insects, but those we know nothing about must run into millions. I have been studying the life histories of the Zimbabwean butterflies for several years, so my observations are restricted to that field.

Some of our butterfly species are dependent on a single plant or tree species for their larval food, while others are liable to utilize two or more species. It is very significant that where additional plant species are used, they are usually quite closely related – same genus or same family. Certain butterfly species are able to utilize a very wide range of plants. The Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) is a good example of this ability, and as a result it is found almost anywhere in the world where there are butterflies. At the other extreme, some butterfly species occupy very restricted ranges, sometimes as little as one or two hectares, although to be fair, climatic and geographic factors are often part of the cause. The presence of a particular butterfly species in an area is usually an indication that its food plant also occurs there. The converse doesn’t necessarily apply, as climatic factors sometimes restrict [a butterfly’s] range in spite of wide-ranging foodplants. A good example of this is the beautiful Flame-bordered Charaxes, Charaxes protoclea azota, which uses both Brachystegia spiciformis(musasa) and Afzelia quanzensis (pod mahogany), and yet is restricted to a fairly narrow strip along the moister (?) Eastern Highlands. Another Charaxes species, C. guderiana, turns up fairly often along the Zambezi River around Chirundu, at least 30 kilometres from the nearest Brachystegia and Julbernardia on the Escarpment, which are its known foodplants. Occasional individuals could certainly fly that distance, but the regularity of its occurrence, and the fresh condition of specimens taken at the river, indicate that it is using an, as yet, unknown tree there. I’m assuming it will be a tree, as the Charaxes, almost without exception, use trees or their saplings. Knowing that, it will most likely be a tree fairly close to the known ones. Tamarindus indica (tamarind) is my guess, or possibly Cordyla africana (wild mango). I have both of these growing at home, so it will be a fairly simple matter to trap a live female, and sleeve-net her on a spray of fresh foliage, where she will lay her eggs if the leaves give her the correct signals. If not, we scratch our heads and try again – Dalbergia or maybe Xanthocercis?

This brings us to the really interesting bit. Leaves of almost any plant, anywhere in the world, contain all the nutrients that any caterpillar needs for growth. The implications of that fact are potentially catastrophic for this planet – all plant life would have been guzzled out of existence long ago if it were not for the control mechanisms built into insects. Let’s examine briefly how a female butterfly locates the food plant in order to lay her eggs. Firstly, the air temperature must be at a reasonable level – at least 25 degrees C. The female first detects the presence of the required plant with her antennae, picking up the minute traces of volatile `essential oils’, as they are known, given off by the plant into the surrounding air. Once she has located it, she flies through and around the foliage, alighting every so often to check the suitability of the leaf via special sensory organs in her feet, known as chemoreceptors, which must give the correct signals if she is to continue.

The age of the leaf is important here, as most species can only use fairly young to mature material.

Dust on the leaf surface will usually make the female reject the plant and move on, as will various repellent substances, like ethylene, which the plant emits when it is already being fed upon by caterpillars. Once the chemoreceptors in the feet, and others at the tip of the abdomen, have been satisfied, egg laying begins. Somehow the butterfly has gauged the size of the food plant, and will lay only a few eggs on it before moving on to seek out others. This dispersion seems to be beneficial to both parties, as the plant is not `overgrazed’, and the predators and parasites have a hard time finding the larvae. The abundance of any particular food plant seems to have very little bearing on the population level of the butterfly species that feeds on it. Julbernardia globiflora is a good example. It is arguably the commonest and most widespread of all Zimbabwe’s trees, and is known to be the foodplant of at least 11 different butterfly species, none of which is particularly common. In all my wanderings in the bush, I have seldom come across larvae of more than one species on an individual J. globiflora. It seems to be a case of first-come-first-served! Once the eggs hatch the larvae usually eat their egg shells as their first meal before starting to eat the foliage, which must now pass a further series of chemoreceptors in and around the mouthparts. Firstly, small 3-segment antennae on either side of the jaws must satisfy the larva that the food is the correct one. Then, tiny sensory palps must also be satisfied. Interestingly, the surgical removal of these palps has resulted in the larva happily eating almost any type of leaf material offered. As if that were not enough, a final set of chemoreceptors is [located] at the beginning of the digestive tract, and these cause a violent reaction if offended, causing the larva to vomit up all it has eaten.

In the wild the larval chemoreceptors are largely a formality, but when one comes to introduced plants of similar genera to local ones, although the female may be fooled by them, the larvae seldom are.

I have done some interesting experimentation where, although a female cannot be induced to lay on a plant closely related to her usual foodplant, her offspring, transferred as eggs, have no choice but to eat the new plant, and it often passes their test, even having failed their mother’s!

While searching patiently a few years ago for larvae of the, then, unknown Charaxes chittyi (recently named after the late JCO Chitty, of Harare), I noticed something very interesting. I had seen females of that species showing more than passing interest in Brachystegia boehmii(mupfuti), and decided that that must be its foodplant. In an area where at least 50% of the trees were B. boehmii, it was a long, drawn-out search, eventually rewarded by the discovery of a few larvae that did finally turn out to be C. chittyi. During the search I had noticed that the very occasional tree had smooth (glabrous) leaves instead of the usual hairy ones, and it eventually dawned that larvae had been found only on these glabrous ones. Thereafter, the search became easy, as I only needed to feel the leaves to know whether to search or pass on to the next tree. I tried to feed hairy leaves to some of the larvae, and they reacted so violently that I might as well have fed them with DDT! It was lethal to them. Can this just be the hairs, or is there a significant chemical difference in the leaves? I have been able to force females to lay their eggs on the hairy leaves, but the larvae were unable to eat them. I have noticed a similar situation with a different butterfly species on Dichrostachys cinerea (chinese lantern, or sickle bush), where the subspecies nyassana, with its hairless leaves, supports larvae, while ssp africana cannot; and yet another on Ficus sur (Cape fig), where only the occasional glabrous specimen will support larvae of the Map butterfly (Cyrestis pantheus), whose life history has only recently been discovered.

As an interesting aside, in April 1992 I took a walk in the Fuller Forest, just south of Victoria Falls, and found that the Brachystegia boehmii there are, almost without exception, all glabrous-leaved. I don’t think Charaxes chittyi has discovered this situation yet! Unfortunately, it was the wrong time of year to collect seed; those that I have carefully collected at Bindura off glabrous trees, and germinated, have produced hairy seedlings, much to my frustration!

One final interesting observation, by no means exhaustively researched, but nonetheless significant, is the fact that of the 85 families of the National Tree List (Drummond 1981), only 31 contain species that are known to be foodplants of butterfly species. Many life histories are yet to be discovered, so there is an incredible amount of hands-on, eyes-on work to be done. Worldwide literature is full of clues for us – for example, the Map butterfly, just mentioned, has related species in South America and the Far East, but no relatives in Africa. Those relatives whose life histories are known are dependent on various Moraceae, which give the clue to where to start looking here. Examining saplings of Trilepisium madagascariensis in Chirinda Forest led to the discovery of very strange larvae, which turned out to be those of Cyrestis pantheus- a great thrill. Since this species occasionally turns up hundreds of kilometres away from its `home’ habitats in the eastern districts forests, we assumed it would also be using a Ficus species, and F. sur proved to be the one – although only the glabrous individuals. The possibility that other Ficus species are also used is very real, and only time and search will reveal it – and such discoveries are their own reward.

[Comment 2000: According to Richard Cooper (1973), Butterflies of Rhodesia (Longman’s Bundu Series), Charaxes protoclea azota is known only from the Burma Valley and Mount Selinda areas in Zimbabwe, but is common in parts of Mozambique. Mean annual rainfall in the Zimbabwe part of its range would be around 1400-1500 mm, and this could not really be described as the “moister” Eastern Highlands.Rob Paré’s discovery that the larvae of Charaxes chittyi will not touch Brachystegia boehmii that have hairy leaves is extremely interesting, and it makes one wonder whether it is the hairs, per se, that make the leaves unpalatable, or some chemical within the hairs, or in hairy leaves generally. “The Book” (Coates Palgrave) says that the upper surface of mature leaves of B. boehmii are without hairs, but that all other parts are finely hairy; Rob Paré’s observations indicate that this description needs revision. Similar observations were made on glabrous and hairy leaves of other tree species with other butterflies, which brings up the question of chemical analyses of hairy and glabrous leaves within a tree species. Chemotaxonomy has been used as a tool in the classifications of Pinus and Eucalyptus, and it would be interesting to see whether it could be applied in some of our own genera. Insect feeding preferences associated with apparently minor morphological differences within a plant species suggest that there may be scope for research into this phenomenon.

Rob Paré’s frustration at finding only hairy seedlings germinating from seed collected from glabrous B. boehmii is understandable, but this is quite common in other species. However, the hairy, juvenile leaves of seedlings give way, in due course, to glabrous leaves in the older plant. It would be interesting to know if this is happening in his mupfuti.

As a follow-up to his article on Plant-Insect Relationships, Rob Paré hosted a Tree Society outing to his farm near Bindura on 15 November 1992.

Rob Paré

The subscriptions are now overdue. If you have not paid please settle, soonest.

TONY ALEGRIA CHAIRMAN