TREE LIFE

August 2013

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Sunday 18th August: Kutsaga

We expect to find some interesting trees in a well-protected habitat. Meet as usual at 0930, and bring all you need for lunch.

Saturday, 24th August. Prince Edward School

By kind permission of the Headmaster and arranged by Leslee Maasdorp, who planted the trees in the 70’s.

ARE PLANTS INTELLIGENT?

Are plants intelligent?

Those of you who have seen “The Private Life of Plants” of David Attenborough will remember how plants conquer new territories, how they defend themselves against predators or how they form symbiotic relations with others. The film was first launched in 1995 and in the last 18 years a number of further discoveries have taken place.

Some 30 years back Jack Schultz, biologist at the University of Dartmouth in The United States, received a phone call from a chemistry student, Ian Baldwin, aged 25 years only, who was enrolled by Schultz to check a hypothesis deemed improbable at the time: the existence of chemical telecommunication between plants. The discovery published in Science in 1983 heralded a new outlook on the Plant Kingdom.

Ian Baldwin, now head of the Marx Plank laboratory of chemical ecology in Germany, recalls that he was put on the track by specialists of animal behaviour such as David Rhoades. They became interested in the Plant Kingdom and transposed the methodology used on animals to plants. Thus, slowly, a new science emerged: the discipline of Plant Ethology.

The aim was to try and understand plants reactions, find their mechanisms, question their ecological purposes, their evolutionary origins and the reasons why they have been selected.

The technological advances in analytical instruments such as gas chromatography have made possible the detection of the minute amounts of chemicals compounds used by plants for the transmission of information. The advances in biotechnologies have allowed scientists to create plants where the expression of some genes have been suppressed or where their expression has been enhanced; with these techniques scientists are now capable to assess the function of specific genes. Advances in motion picture technology make possible the visualisation of minute movements in organs such as the radicles of plants.

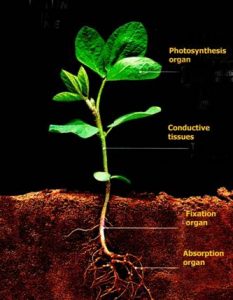

So far some 700 kinds of sensorial signals have been identified in plants: mechanical, chemical, thermal, luminous that is generally more sensitive than ours. As a matter of interest plants have more genes than animals, for instance a grain of rice has twice as many genes as man. There are two major differences between plants and animals, first they can transform light into food by photosynthesis, secondly, and as a consequence of this ability, they are fixed.

It is this inability to move that is the cause of the extreme complexity of plants: they have to find metabolic solutions to the same problems as animals but without moving. Their sensibility to light is much higher than ours, they can detect it at much lower levels than us and in a broader spectrum, both in the ultra-violet and the infra-red ranges. Their sense of touch is fascinating; they can detect the slightest touch as well as the orientation of their branches and roots. But their highest ability is in the production/ reception of chemical signals. In a meadow, where we cannot smell anything, plants receive continuously chemical information on the state of their surroundings. We will now look at some of the example of tree behaviour under different circumstances.

Plants have many ways of communicating.

The aerial way of communication between plants is very extensive and has been well documented over the last 30 years. Experiments have shown that plants alert each other by the emission of volatile compounds.

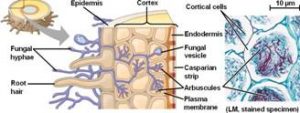

Less known is the subterranean communication path as it is more difficult to research. Yuan Song from the Laboratory of Ecological Agriculture in Guangzhou (China) has proved the existence of the underground path in 2010 using tomato plants. When a tomato plant gets a disease it warns the neighbouring plants via a root mycorrhizae.

After planting tomatoes in pairs the researcher introduced a predator in one of the plant of each pair. In the presence of the specific root mycorrhizae, the healthy plant of the pair starts producing defence enzymes, normally synthesised when the plant is attacked. On the contrary if the mycorrhizae are absent or if a physical barrier is inserted between the plants of the pair the defences of the healthy plant are not activated: the signal has been blocked.

Many of our indigenous trees have a symbiotic relation with specific mycorrhizae

As a matter of interest many (if not all) of our indigenous trees have a symbiotic relation with specific mycorrhizae. That is why if you plant an acacia or a brachystegia you should get a bucket of soil from the foot of a thriving tree in its natural environment to plant your new tree. And if your beans or peas don’t do well in your garden the cause might well be the absence of mycorrhizae in your soil. By the way mycorrhizae are species specific and so far some 75 000 species of fungi have been identified and researchers believe they have only scratched the surface.

Adapted from ‘Science and Life’ March 2013.

– JP Felu TO BE CONTINUED

TREE OF THE MONTH

This month’s Tree of the Month article was kindly written by Meg Coates Palgrave. The subject is Lannea discolor. – ed.

Lannea discolor

Tree of the Month is the Live-long, Lannea discolor, and that’s the name ‘coz its dis colour and not dat colour. The specific name comes from the fact that the leaves are discolorous with the upper surface green and the lower surface with a dense matt of greyish to whitish hairs.

Some of the Shona, Ndebele and Tonga names are a variation on the stem –gangacha or gangatsha which I understand means never-die or cannot be destroyed. Those names refer to the tree’s amazing resilience and ability to survive. They coppice readily, sending out new shoots when cut down and even after being removed they grow again from the roots. I have seen one coming up in the middle of steps made from boulders. Trunks used as truncheons also strike and grow.

Lannea discolor leaves

The trees seen around Harare are survivors of when the area was natural woodland. They lose their leaves soon after the end of the rains and stand bare for several months. But like many deciduous trees which are leafless for a long period there is chlorophyll just under the skin of the bark and they are able to go on photosynthesising even without leaves. If the bark is gently scratched with a finger-nail the green is visible.

Another survival strategy is the presence of lenticels on the bark. These are tiny corky breathing spots that allow the exchange of gases, so they are able to go on breathing even without leaves.

The trees are dioecious, the male and female flowers are borne on different trees or, as Linnaeus described it, husband and wife in different beds in different houses. The flowers and fruit are borne at the ends of the branches before the new leaves appear also at the ends of the branches resulting in the tips being scarred and knobbly and this is a very distinctive feature particularly when the trees are standing bare.

The flowers and fruit are borne at the ends of the branches

The ends of the branchlets are sometimes described as resembling ‘ET’s fingers’ for those of you who remember the film ET. These trees are reported to be easy to grow from seed and cuttings but are sensitive to frost. Why not try one?

Meg Coates Palgrave

Visit by the Tree Society to the home of Rob and Sheilah Jarvis, at 14h30 on Saturday May 25, 2013.

There is plenty to interest the plant lover at Rob and Sheilah’s large property opposite the fields of St John’s College in Rolf Valley. A gigantic Kenyan coffee shade, Acrocarpus fraxinifolius, towers over the house, and the owners are proud to name this tree as Harare’s tallest. The coffee-shade grows near the garage, to the right of the main house, and on the other side of the house grows an equally magnificent fever tree, Acacia xanthophloea. The latter tree was planted when Rob and Sheilah arrived at Rockyvale close in 1991, and now stands close to 20m tall. The Coffee shade must be 40m high at a guess.

The Jarvis garden is large and tantalisingly complex – it would take many walks to fathom the mysteries of its design, to say nothing of the plant life within it. The area close to the house contains many planted specimens jostling each other in what must be quite an ecosystem in itself. An instance of the latter phenomenon is the swimming pool area, now converted to a pond, which would certainly repay an afternoon’s exploration.

Round the far side of the house, at the other end from the coffee shade, is a rockery, and on this grows the Carrion flower, Stapelia gigantea, whose giant 40cm flowers are a deep gold colour and are as unmistakeable as the plant’s aloe-like spiny stems.

Proceeding along the path we came to another tree which is rare and specially protected – Bivinia jalbertii, the Cobweb seed. This tree only occurs in a few isolated areas of Zimbabwe, which experience mist and winter rain. Near the Cobweb seed is a specimen of Cordyla africana, the Wild mango, whose distribution is also somewhat restricted in the country.

A little further on we came to an Eastern Highlands forest species, Podocarpus latifolius or Real yellowwood. This tree has a false fleshy aril around its seeds, which are reputed to be the favourite food of the Cape parrot, according to Peter Hadingham. Cardiospermum grandiflorum, with its heart-like seed, is a very successful invader, and a young progeny of the giant Kenya Coffee-shade, Acrocarpus fraxinifolius, also lurks in the woodland here.

A member of the Combretum family also showed its presence – it had dark, dense leaves and coffee-coloured stems, possibly Combretum apiculatum, the Red bushwillow, though Mark and Meg were not sure.

Another interesting feature of the Jarvis property is a bucket-fed rain forest. This was planted at the time of the great drought of 1991-2, and was intended to be fed by a nearby dam, built by the then new owners. Although the dam never filled up and remains empty, some riverine species still flourish here, including Combretum erythrophyllum, the River bushwillow. Densely foliaged and potentially tall, this plant can form thick stands by rivers in the wild.

There is also a Tamboti, Spirostachys africana, a tree with varied and contrasting attributes: satiny and fine heartwood which seems to be near-indestructible, burns with an aromatic but noxious smoke, and exudes a plentiful sap which is highly poisonous but has been known to cure toothache. The Tamboti belongs in the family Euphorbiaceae and has unisexual flowers.

A specimen of Euclea natalensis grows in the woodland as well. Called the Hairy-leaved guarri, this tree will grow in coastal dune land and in miombo woodland, and a variety of altitudes in between and must be quite unusual for this reason.

Probing further into this intriguing woodland we came across a species of Gardenia with whorled leaves, then Clerodendrum eriophyllum, the Hairy tinder wood, and the bipinnately compound Albizia gummifera, which is most often found in high-altitude forests.

A little further on was some abundant foliage of leaves 3-veined from the base, making them billow out like basil leaves, and this turned out to be the Grape strychnos, Strychnos potatorum, growing near a small specimen of Khaya anthotheca, the Red mahogany, which can grow to be one of the biggest and most famous timber trees in Zimbabwe.

A Toad tree, Tabernaemontana elegans, inhabits this garden as well: Its fruits, called paired mericarps, are wrinkled brown and warty, resembling a toad’s head, an unmistakeable label. Bridelia micrantha, the Mitzeeri, was here too, its leaf-veins running straight to the margin, as was Schotia brachypetala, the Fuchsia tree or “Weeping boer-bean”, which will be in spectacular deep red and delicate pink flower if we visit again in September or October.

The woodland by the boundary of the property, as one proceeds left up past the empty dam, is of a more natural type with less planted specimens, and includes a Marula (Sclerocarya birrea), a Broad-leaved beechwood, Faurea rochetiana, and a foot high Mopane tree which Meg observed and which seemed to owe its diminutive stature to an acidity in the Highveld soil and perhaps also to a shortage of clay. Mark pointed out Commiphora mollis, the Velvet corkwood, the Corkbush, Mundulea sericea, Croton megalobotrys, the Fever berry, the climber Cissus quadrangularis, the Woodland dog plum, Ekebergia benguelensis, and the Tassle-berry, Antidesma venosum, whose small fruits are edible and reasonably tasty.

Having viewed more than 30 plants we navigated our way back to the house for a very enjoyable tea.

Richard Hartnack