TREE LIFE

June 1997

If you haven’t already done so, please pay your $40 annual subs, which were due on 1 April.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Saturday 7th June: Botanic Garden Walk. We will meet Tom in the car park at 10.45 for 11 a.m. Over the next couple of walks Tom will be showing show us some of the palms and cycads in the Gardens. Lists will be available, but if you still have yours from the May walk please bring it with you. There will be a guard for the cars.

Sunday 15th June: A ramble along the foothills of Ngomakurira – always an interesting venue. Plants to look out for are Faurea delevoyi, which we remember as Faurea subsp. No.1 and an unusual Syzygium growing along the river, probably Syzygium guineense subsp. afromontanum.

We will meet at 9.30 am.

Saturday 28th June: Mark’s Botanic Walk will be at another of our favourite haunts – Greystone Park Nature Reserve. we meet at 2.30 p.m.

Saturday 5th July: Botanic Garden Walk.

August 8th to 12th: (4 nights) First come basis for a long weekend in the Vumba. Cottage accommodation for 17 people has been reserved at Seldomseen. Self-catering and $400 per person. Please phone Maureen Silva-Jones a.s.a.p.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Sunday 1st June: To How Mine to look at Olea europaea subsp. africana. Please meet at the car park at Girls College for departure at 8.30 a.m.

Monday 9th June: Study Session. Urban trails in Circular Drive area. Meeting at 5-5.15 p.m. These sessions will take place on the second Monday of every month.

TULI Friday 28th March

For a number of us the Tuli district would be new and exciting territory to explore and we thank Maureen for organising the wilderness camp for us.

At first sight the Tuli area appears as a topography of shallow hills at low altitude with the strange physical feature of this arid area being thin soils littered with small broken rocks which, due to weathering, appear like the frozen remains of a muddy bubble about to burst, an onion skin effect to be correct. The river here is a wide swathe of sand, half of which is covered with a shallow flow of water and is, in fact, the Shashe; the Tuli River joining many kilometres upstream.

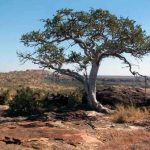

Sesamothamnus lugardii. Photo; Rob Burrett. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

It is in this unusual landscape composed largely of basalt with scattered grass cover that one finds an unusual species which is restricted to the Limpopo basin – Sesamothamnus lugardii, resembling an outsize Adenia at first glance with a squat bole supporting multiple stems; being the end of the rainy season the branches were covered in short stiff leaves giving the plants a strange fuzzy appearance. A shallow hillside just north of Tuli is home to another curiosity – Adenia spinosa, this particular plant though masked by a clump of Mopane has a pea-green succulent trunk oozing over the rocks. Strong spines are also present hidden by the leaves while the forming fruits appear granadilla-like, not surprising really as the species belongs to the family Passifloraceae.

Wonderful weather with our first day starting delightfully cool and grey though this does not help with early morning starts. Within a stone’s throw of the thatched camp and still in the riparian zone of the Shashe River, the variety of flora and fauna is impressive. Ranging from the huge Ficus sycomorus, like those in the Zambezi Valley, with huge buttressed yellow boles and an enormous spread tempting Douglas to contort himself into a strange position in pursuit of photographic excellence, to a spectacular Schotia with a resident Mopane squirrel family who also utilized the dining hall thatch for warmer and more comfortable evening lodgings. Around the camp our old friend Ziziphus mucronata assumed a Grewia-like shape with long slender shoots and Terminalia prunioides resplendent in swathes of purple fruit seemed to be the most common plant around along with mopane of which some bore swollen green kidney-shaped fruit. The cool green groves of Nyala berry – Xanthocercis zambesiaca – the river seem to produce fruits in quantity and in the depths of the foliage a few Grey Lourie crashed about whilst investigating the green state of the crop. Not many succulents are to be seen around the camp except for two planted clumps of the curious genus Stapelia, the large pink flowers being those of Stapelia gigantea and the more hairy belonging to Stapelia gettleffii. Both sets of plants produce flowers with a foetid odour to attract flies that pollinate the plant as they buzz about and wander drunkenly over the stamens in pursuit of the aroma. The shrubs, which include Pluchea leubnitziae, a composite that is erect and grey-green with a foetid odour, released from damaged leaves.

Rhigozum zambesiacum. Photo: Meg Coates Palgrave. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

And Rhigozum zambesiacum, which produces a spectacular array of yellow blossom at the onset of the rains and being a plant of arid regions some spines are present masked by the small pinnate leaves.

The stony hillsides are also the home of Albizia brevifolia, multi-stemmed and with a delicate feathery appearance, Boscia albitrunca with white patches on the trunk and another new one for me – Commiphora tenuipetiolata that has a long delicate petiole supporting the leaves.

Commiphora edulis is a frost resistant species and has the typical peeling bark of a grey to green colour. The leaves of this species are compound and relatively large with the leaflets being surprisingly hairy and Anthony informed us further that the roots are edible (for elephants?). Here the venerable giant Baobab of Tuli is found where names and dates have been cut into the great snaking roots, from a faint 1926 to a number of ’55 and ’60 additions as well as more recent entries. One wonders how many pioneers, hunters, and latterly schoolboys have camped beneath its enormous spread for nearby the scars of the Zederburg coach trail cut into the shallow rise, however, slowly but surely the Acacia’s advance will one day obliterate all but the broken rocks.

Tiring of shrubs and trees, Anthony disturbed a horned adder while turning over rocks in search of scorpions and some excitement. While at rest the adder remained a flat coil with the diamond pattern of its skin producing a really effective camouflage, however, once goaded into action the rapid intake of air allows the snake to puff up to almost twice its original size, the horny projections behind the eyes are raised to the maximum when coiling and striking. After a good half hour of activity the excited flickering of the serpent’s tongue and Anthony’s trembling hands while trying to fasten a camera lens said it all.

An afternoon drive to a spot a short distance down river provided another wander along thickly vegetated banks. Of interest was Datura ferox whose seed capsule has the curious habit of pointing downwards. This plant has spread rapidly and successfully along the sand banks. The shallow waters of the Shashe River invited a paddle to end off a most enjoyable day before returning to camp.

Andy MacNaughtan

Easter Saturday in Tuli Circle.

With a game scout in attendance we set off for the Circle, the precious cargo of our two septuagenarians – Mary and Dick accompanying our lunch in the two vehicles. The rest of us trudged across the deep loose sand and in places waded through the knee-deep river to the other side 800m away. From there we set off for a look at the historic Fort Tuli, and tried to picture ourselves with the pioneer column in the 1890’s and later during the Boer War. Not much remains of the fort itself but the prison must have been a substantial building much of the walling having survived. A little further on is the cemetery, which is well preserved; the headstones, which can be easily read, tell many a tale of fever, lion attacks and other misadventures. A deep trench surrounds the cemetery and this has effectively kept the elephants out. There are still many pieces of rusty tin, and broken glass and pottery littered around the Fort.

The vegetation here is sparse, with dry grass, some herbs and a few good specimens of Commiphora hereroensis, Boscia albitrunca, Croton megalobotrys, Commiphora glandulosa, and a fine Kirkia acuminata.

On the way to the Fort Mark had spotted Acacia permixta which so excited Anthony that he was drawn back to spend a good hour in its company looking for seed and other specimens. Back to the river for lunch, the Ficus sycomorus providing a splendid perch for Anthony and a shady lunch spot for us. Later in the heat of the day we walked northwards to where a river enters the Shashe, (dry now) but the Ficus sycomorus here are the most magnificent I have seen, and as Richard pointed out, favoured too by a nesting Meyer’s parrot who periodically popped out of her hole to inspect the intruders. One of these fig trees housed a huge hive of bees.

A walk along the riverbed led us back to camp, gathering along the way some fruit of the Hyphaene petersiana, (vegetable ivory). A happy day of botany and history in good company.

-Maureen Silva Jones

Easter Sunday

On the last day of our stay at Shashe we set out at about 9 a.m. for the Tuli River/Shashe River confluence. The MacFarlanes had decided to take it easy and stay near the camp for the day, so only two vehicles set out on this day. We were indeed fortunate that we had two 4 WD vehicles at our disposal, and we were most grateful to the owners for allowing us to combine with them.

Out first stop was at the Hwali River Bridge where we spent about an hour. On a hill overlooking the Hwali River we saw several plants of interest apart from the smaller stuff that Mark was concentrating on. There were many Sesamothamnus lugardii in the area, a colony of Aloe globuligemma, some Euphorbia cooperi and a number of plants of Adenia spinosa, which had male flowers, and some fruits that unfortunately were not ripe.

Trees seen

Acacia nilotica, Acacia nigrescens, Acacia senegal, Acacia tortilis, Boscia albitrunca, Albizia brevifolia, Combretum apiculatum. Commiphora mollis, Catophractes alexandri, Cordia ovalis, Commiphora africana, Grewia bicolor, Commiphora glandulosa. Grewia flava, Commiphora tenuipetiolata, Ochna sp., Combretum hereroense, Combretum mossambicense, Kirkia acuminata, Colophospermum mopane, Dichrostachys cinerea. Euphorbia cooperi, Euphorbia guerichiana, Grewia flavescens, Grewia villosa, Markhamia zanzibarica, Ficus abutilifolia, Lonchocarpus capassa, Rhigozum obovatum, Sterculia rogersii, Sclerocarya birrea, Terminalia prunioides, Ximenia americana

Shrubs, herbs and climbers.

Abutilon angulatum, Kalanchoe sp., Aloe globuligemma, Lantana triphylla, Cardiospermum sp., Adenia spinosa, Sansevieria deserti, Senna italica, Acalypha pubiflora

Throughout our visit to Shashe we had cool cloudy conditions and this day was no exception.

We then set off for the bridge over the Tuli River. On the way Mark first noticed some Acacia borleae, which was the second of the glandular, podded acacias that we saw on this trip. Acacia borleae is distinctive in having thin hairs or cilia on the margins of the leaflets when viewed through a x10 lens. We returned to these plants on our journey back to Shashe Camp in the late afternoon when we were lucky enough to be able to collect a good number of seeds for distribution to interested parties.

On reaching the Hostes Nicolle Bridge over the Tuli River we stopped on the northern side or western side and continued our plant explorations, where we saw the following

Acacia albida, Acacia erubescens, Adansonia digitata, Bridelia mollis, Commiphora edulis, Ehretia rigida, Diospyros lycioides, Gardenia volkensii, Grewia monticola, Ficus sycomorus, Combretum erythrophyllum, Hyphaene petersiana, Nuxia oppositifolia, Lannea schweinfurthii, Xanthocercis zambesiaca.

Shrubs and climbers

Acalypha pubiflora, Pergularia daemia, Cocculus hirsutus, Plumbago zeylanica, Cissus quadrangularis, Corallocarpus triangularis, Ctenolepis cerasiformis, Momordica balsamina

Mark was again able to collect many specimens of flowers and smaller shrubs.

Our last stop before heading for home was to locate the confluence of the Shashe and Tuli Rivers. After a not so long and winding route and with the help of one of the local inhabitants we reached our destination where we settled down to a leisurely lunch on the river bank just downstream from the confluence. There was virtually no flow from the Shashe River, but there was a fairly strong stream of water flowing in from the Tuli River.

After lunch we did a bit more wandering around up and down the riverbank. We again found more of the distinctive spiky legume (Indigofera?) that we had found near the Shashe Camp and in the Tuli Circle (semicircle).

There were some very big Commiphora edulis close to the river – 20-30′ high!

At this venue we added Acacia mellifera to the list of plants seen.

We headed back to camp having enjoyed the day treeing and sight seeing. Other plants noticed on the way back to camp were Commiphora viminea, Cassia abbreviata and Cissus cactiformis.

For me the highlight of the whole visit was seeing Acacia permixta for the first time and being able to collect seeds.

The peace and tranquillity of visits to the bush is of course always a big plus. It was so good to meet new members from Harare too.

-Anthony Ellert.

THE TALL, THE FAT, AND THE ANCIENT (Cont.)

THE ANCIENT.

Here we sometimes leave the world of measurement and verifiable data, and enter the realm of estimate and speculation – and legend! – although carbon-dating techniques have been put to use in some cases. At one time the giant sequoia, Sequoiadendron giganteum, was believed to be the longest-lived tree at around 3000 years, followed by the coast redwood, Sequoia sempervirens, at around 2000 years.

But then detailed studies were carried out on the bristle-cone pine, Pinus longaeva, at about the time it was separated as a species distinct from Pinus aristata, and a specimen was dated at 4700 years, with a potential life span for the species of 5500 years. More recently there appears to have been some re-thinking on the ages of the giant sequoia and the coast redwood, and serious estimates of 6000 and 6200 years, respectively, have been proposed as the potential ages of these two species. I have seen no papers in support of these estimates, and would not like to comment on them. But it is interesting to note that whereas the giant sequoia and the coast redwood commonly have mature heights of 100m or more, the bristle-cone pine takes all of its 4700 years to reach a height of 12m!

The famous Dragon Tree of Tenerife in the Canary Islands, Dracaena draco, was supposedly 6000 years old when it blew down in a storm in 1888. At that time it had reached a height of 21m and a girth of 14m. This legend apart, there were well-authenticated specimens of the species with a life span of over 2000 years, which must be unique for a monocotyledonous tree. Today there are apparently no specimens more than 400 years old.

Large African Baobab, Adansonia digitata, are now thought to attain 3000 years, possibly on the strength of the carbon dating of a tree of very modest diameter (4.5m or a girth of 14.14m) from the Kariba basin whose age was established at 1010 years, plus/minus 100. The French botanist Michel Adanson, after whom the Baobab was named, examined two large specimens off Cape Verde in 1749, and calculated an age for them of 5150 years. A hundred years later this claim roused the indignation of David Livingstone, who belonged to the school of thought that had calculated the Year of Creation as 4004 BC. What annoyed Livingstone was that Adanson’s dating had these baobabs alive before the Great Flood – with the inference of no Flood!

There has been much speculation in the past about the possible age of the Big Tree of Chirinda Forest, Khaya anthotheca and the consensus of those who have actually stuck their necks out in print would have an age of around 1000 years. Since the tree is dying fairly rapidly there will soon be the opportunity to obtain samples for carbon dating, which would be of immense scientific interest.

In Britain the English yew, Taxus baccata, is known to live for at least 1000 years, and there are authenticated specimens of that age in various cemeteries.

According to legend an ancient plane tree, Platanus orientalis, on the island of Kos (or Cos) in the Aegean, provided shade for the great physician Hippocrates (? 460-? 377 BC) while he instructed his pupils and followers in the (then) new science of medicine. In 1960 Sir William Murphy, former Acting Governor of Southern Rhodesia, collected seed from the tree, and one of the resultant seedlings was planted in 1966 in the grounds of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Zimbabwe.

In 596 BC the Indian Prince Siddharta, now better known as Guatama Buddha, sat under a peepul tree, Ficus religiosa, at a place called Uruvela, to meditate (some say for seven weeks, others for seven years) until he received the enlightenment that brought him Buddhahood. According to legend a seedling from that tree was planted in 288 BC in the ancient city of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, and every year of its life since then has been carefully recorded.

When a plant propagates itself by continuously suckering there is seemingly no finite age for the resultant clone, even though each ramet (the individual entity of a clone) does have a limited life. One very long-lived clone of the creosote bush, Larrea tridentata, dubbed “King Clone”, has survived for an estimated 11700 years in the Mojave Desert in the United States. How this age was arrived at is not known to me.

Finally, among the ancient species still present in the world today we have the maidenhair tree, Ginkgo biloba, which has survived for 200 million years; the water fir, or dawn redwood, Metasequoia glyptostroboides, for 136 million years; and the recently discovered Wollemi pine, Wollemia nobilis, for 90 million years; and all of them have fossil evidence to prove it! Coming closer to home, the propeller tree, Gyrocarpus americanus, which occurs in southern Africa, South America, and Australia, must date back to before the break-up of Gondwanaland around 135 million years ago – that is, if the botanists are right in saying that it is the same species across all three continents.

-Lyn Mullin

LICHENS

According to a recent article in National Geographic, lichens are attracting new attention for their medicinal, decorative and pollution detecting properties.

Despite their plant-like form, lichens are not plants. They are a symbiotic combination of a fungus with an algae and/or cyanobacteria. Fungi, algae and bacteria now occupy classifications of their own, in addition to the two traditional “kingdoms” of plants and animals.

The pigments, toxins and antibiotics contained in lichens have made them useful to people in many areas of the world for centuries.

Lichens have provided dyes for the Navajo Indians’ rugs, Scottish tweeds and the royal purple of Roman times.

Their medical properties have been utilised in teas, skin salves and modern antibiotic creams. Some lichen species are food for animals and humans.

Growing almost anywhere with a stable surface – from stained glass windows of cathedrals, to the backs of Galapagos tortoises – lichens are among the world’s oldest living things, making them useful for dating artefacts or geological events such as the retreat of glaciers.

Because of their sensitivity, lichens are indicators of air quality, absorbing pollutants that can be measured by chemists.

Pollution is a threat to lichens, even in the Arctic. Fallout from Chernobyl contaminated lichens eaten by reindeer. Tragically the animals had to be destroyed.

-A J MacFarlane From an article in National Geographic dated February 1997.

TREES AND OTHER PLANTS OF DAVID LIVINGSTONE’S ZAMBEZI EXPEDITION 1858-1863

Continued from Tree Life No 207 May 1997.

MOCHABA. 24 August 1858: “We found a log of mochaba, the toughest to split I ever met with.”

The wood of this tree was cut up for the boiler of the steam launch during the exploration of the Shire River, but it evidently didn’t take them much distance for, in the same journal, Livingstone wrote, “By means of it we got to the old woman’s garden opposite the islands. Not being aware that the steam was let down by the wood being all expended. I tried to run on shore at dark.”

The identity of mochaba is uncertain. The Tonga name ‘muchaba’ refers to Pteleopsis anisoptera, a shrub or small tree that is unlikely to have been the subject of Livingstone’s journal entry. Muchaba is also a Lozi name for Ficus sycomorus, just as unlikely a candidate as Pteleopsis.

As a long shot, various Grewia species are called muchabachaba in Lozi, and may be rated tough, but very doubtfully large enough for logs.

MBURI. 4 October 1859: “Mburi – name of Plumbago at Mbane.”

This species was noted by Livingstone in present-day Malawi in the Zomba region. It was possibly Plumbago zeylanica, a straggling shrub with white flowers. The popular blue-flowered Plumbago auriculata comes from the eastern Cape and Natal.

MAPIRA. 31 August 1858: “Mapira is the name of the large millet or sorghum and Mapira manga of Maize (Foreign mapira).” The indigenous mapira is Sorghum bicolor, known as mashava or maphunde in Shona, and amabele in Ndebele. The grain may be red, brown, or white. Sorghum is probably native to tropical Africa and has been cultivated from ancient times.

MOCHISA. 28 January 1860: “Mochisa, a good fruit, contains India rubber.”

This entry was made on the lower Zambezi between Sena and Shupanga, and the species was almost certainly Manilkara mochisia, the lowveld milkberry, which is quite common at medium and low altitudes. It is usually a small tree but there is a fine specimen 18m tall and 85cm in diameter at the Deteema picnic site in Hwange National Park. All parts of the tree have milky latex – Livingston’s “India rubber” – the fruit is edible, and the wood is very hard, heavy, purple-red, and termite proof. The Tonga name is muse.

MOKUCHONG. 4 June 1860: “Sleep under a Mokuchong tree in fruit. Up country Batoka call it Moshoma – here Chenje.”

Livingstone wrote this journal on his march up the Zambezi River from Tete, six days after passing the Cabora Bassa rapids. His Mokuchong tree was Diospyros mespiliformis, wild ebony, known in Shona as mushuma or mushenje and in Ndebele as umdlawuzo. It is widespread at low and medium altitudes and can reach very large sizes. The fruit is good eating and the wood sometimes displays the black heartwood of true ebony. It was formerly used in wagon construction.

MOKUNDUKUNDU. 29 December 1860: “The wood of Molundukundu resembles [quinine] or cinchona tree very much; is also very bitter and febrifuge.”

Livingstone was at Shiramba, upstream of Sena on the lower Zambezi and his Molundukundu was almost certainly Crossopteryx febrifuga, which, as its specific name implies, has been used to reduce fever. It is widespread at the lower altitudes in Zimbabwe, usually as a shrub or small tree, but occasionally quite large specimens are seen. The vernacular names are [Shona] mubakatirwa, mukoko, mukombigo, muteyo, and [Ndebele] umphokophokwana.

MOLOMBURU: 5 February 1862, in a letter to Jose Nunes: “I cut a piece of the Molomburu tree to mend the rudder of this ship and left it on the beach till we come back.”

Molomburu was possible Mukwa, Pterocarpus angolensis, which is known in some parts of Mozambique as Mulombwa among other names.

MOLOMPI: 27 December 1859: “Cut down a Molompi tree. It yields a large quantity of red gum.”

31 December 1859: “We got specimens of Molompi, a fine tough wood and fine grained.”

10 March 1860: “Molompi, a Pterocarpus, grows readily when cut down. It yields a kind of gum in great quantity when wounded: floats readily.”

These journals were written on the lower Zambezi between Shupanga and the coast. Molompi, clearly, refers to Mukwa, Pterocarpus angolensis, and the fact that it was found down to the coast strengthens the belief that molomburu, above, is the same species.

MOLOMPWE: 7 September 1861: “Bows [? Made of] “Molompwe.”

This was written during the boat exploration of the western shoreline of Lake Malawi. Molompwe was possibly another variant of molompim Pterocarpus angolensis or it could simply have been one of Livingstone’s many inconsistencies of spelling. But on other occasions he may have used the same name for Pterocarpus antunesii, for which the traditional uses he recorded in other writings are more typical.

MONGA: 10 June 1883: “A thorn tree called monga has a very strong smell, partly of garlic. It is an acacia.”

This was written on the Shire River a little below the Mpatamanga Falls, and Livingstone was probably referring to Acacia sieberiana, the paperbark thorn or umbrella thorn, which is widespread and common in Central Africa southwards to the Natal coast. The wood has a distinctive smell when freshly cut, but whether this can be described as “partly of garlic” is a matter of individual opinion. One of the Shona names for the species is muunga, close to Livingstone’s monga, but the name muunga is also applied to a number of Acacia spp. that have straight, light-coloured thorns or markedly fiat crowns.

MOPANE: 9 June 1860: “Mopane plains; low scrubby acacia bush and many marks of buffalo and rhinoceros.”

This journal was written on the overland march from Tete to Victoria Falls, in the part of the Zambezi Valley now covered by Lake Cabora Bassa.

Mopane is, of course, Colophospermum mopane, the dominant tree of the hot, low-lying areas of south tropical Africa.

MORANYURU: 5 February 1882, in a letter to Jose Nunes: “I write to tell you that the Captain of the brig would like a cargo of wood of the sort called at Shupanga Mozimbiti, at Tette Moranyuru, in English and Latin Lignum vitae …”

Livingstone was discussing Combretum imberbe, which he used for firing the boilers of his steam launch whenever it was available. See above under LIGNUM VITAE.

MOSANYA: 6 September 1858: “We found a piece of African oak or teak last night. It is named Mosanya …”

This journal was written on the Zambezi River a little downstream of its confluence with the Mazowe, and the tree in question was probably Erythrophleum africanum, the ordeal tree, known to the Ndebele as umsenya and to the Shona as mushati. It has a hard, durable reddish-brown wood, but Livingstone’s name, “African oak” is not understood.

MOSEZA: 4 August 1860: “Moseza – Indigo: so called by Barotse. Very abundant tree.”

This journal was written about four day’s march from Victoria Falls and the plant referred to was probably one of various species of Indigofera, possible Indigofera rhynchocarpa which grows to a height of 2-3 metres. In dispatch no.11, Livingstone noted that “indigo is met with as tall as a man.” Indigofera is large genus of more than 300 species but only five of them reach tree size, and of these Indigofera rhynchocarpa is the only one that occurs in the Zambezi area.

The species that furnish commercial indigo are Indigofera leptostachya, Indigofera tinctoria, and Indigofera anil. The plant is mown just before flowering and then soaked in water, when a yellowish solution is obtained. This oxidizes on exposure to the air, and an insoluble precipitate of indigo is formed.

MOTONDO: 5 December 1858: “We got one tree of very good Motondo: one of this fruit [sic] measured 8 inches in circumference and was 3 inches long. The gum is good.”

This was written near Tete on the Zambezi and certainly referred to Cordyla africana, the wild mango, one of the great riverine trees of the Zambezi Valley and other low-lying regions, as far south as Swaziland and adjacent parts of Mozambique. It has an edible fruit with high Vitamin C content, and a hard, brown wood that is used for making African drums. The tree exudes a gum-resin.

Occasional magnificent specimens of this tree are seen, such as the one at Buffalo Bend on the Mwenezi River, in Gonarezhou National Park, which has a crown diameter of nearly 60 metres. The Shona name is mutondo, Tonga mutondo and Hlengwe ntondo.

MOTSIKlRE: 30 July 1859: “Plants and seeds to India and Natal of buaze and Motsikiri.”

This was written at the coast but there is no indication of where the “plants and seeds” were actually collected. However, motsikiri was undoubtedly Trichilia emetica natal mahogany, which is so common on the Zambezi and goes by the Shona names of mutsikiri or muchichiri. It is a commonly planted shade tree in Zimbabwe.

-Lyn Mullin. To be continued.

ANDY MACNAUGHTAN CHAIRMAN