TREE LIFE

July 1997

Subs ($40) for the year 1997/98 were due on 1st April. If you see a red dot on your Tree Life, it is to remind you that payment has not been received and that this will be the last issue that we can send you.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Saturday 12th July: Botanic Garden Walk. (PLEASE NOTE THE CHANGE OF DATE). We will meet Tom in the car park at 10.45 for 11a.m. Tom will continue with the fascinating topic of palms and cycads growing in the Gardens. Lists will be available, but if you still have yours from the June walk please bring it with you. There will be a guard for the cars.

Sunday 20th July: Pam and Frank Wilson have very kindly invited us to visit their farm in the Pote Valley in the Bindura area. The farm has diverse vegetation types and is sure to be of great interest.

Saturday 26th July: Mark’s Botanic Walk will take place in Greenwood Park, which we believe was the original Botanic Garden. We will meet at 2.30 p.m. at the corner of Fife Ave and 8th Street. Both indigenous and exotic species have been planted over the years, so if you have some knowledge of garden plants please come along.

Sunday 2nd August: Botanic Garden Walk.

August 8th to 12th: Seldomseen is well known to many of our members, particularly for the ornithological and botanical knowledge of the previous owners – Alec and Celia Manson.

The cottages are close to patches of natural forest, full of tantalizing eastern districts species that always pose a challenge. Phil and Cheryl Haxen (the new part owners) have some special places to show us and Mark will be our botanical adviser. Cottage accommodation for 17 people has been reserved for 4 nights on a first come basis. Self-catering and $400 per person. Please phone Maureen Silva-Jones a.s.a.p.

October 2nd to October 5th: If there is sufficient interest we will have another trip to the Zambezi Valley staying at the RIFA camp. Please phone Maureen Silva-Jones if you think you would like to be part of the group.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Sunday 6th July: An all day visit to Mbalabala Natural Resources Botanical Reserve. Please meet at the car park at Girls’ College at 8 a.m. for departure as soon as possible after that.

Please note that the Monday evening walks at Circular Drive have had to be terminated due to poor attendance.

Sunday 3rd August. Morning only trip to the Luveve area.

Friday 31st October to Sunday 2nd November:

Weekend trip to Gwaai Valley Safaris overlooking the Gwaai Valley. Would those interested in participating in this function please make contact with one of the Bulawayo Committee members for further details and to give a rough idea of numbers. Camping and self-catering lodges available.

Some months ago Lyn Mullin asked if anyone knew the fate of certain ‘historical trees’ in Bulawayo.

Recently the chairman of the Bulawayo branch, Anthon Ellert kindly assisted by Allison Ewbank located them and reports that – “All are still alive and well”.

1) ‘The Hanging Tree’ situated outside Essex Court between Connaught and Masotsha Ndlovu Road on Main Street – Lannea schweinfurthii.

2) ‘The Signal Tree’ situated” on 1st Ave in Suburbs between Duncan Road and Heyman Road – Lannea schweinfurthii.

3) ‘The Flag Tree’ situated in the premises known as ‘The Grange’ owned by Mr. Patel – Kirkia acuminata.

4) ‘The Mission Tree’ situated on Umvutsha Farm owned by the Fletcher family – Combretum imberbe.

BOTANICAL GARDEN WALK: 7th June 1997.

The walk began with a mugging. One of our members, Ian Riddell, was attacked in broad daylight quite close to the car park just before our meeting and appeared, shaken and bleeding, minus his wallet. An immediate search of the area and 5th Street extension by various members produced no result. This incident, following on from a number of recent incidents, shows that the Botanic Gardens are a place to be wary of, until the authorities get on top of the problem.

Our subject today was the palm family. Apart from a superficial knowledge of the 4 native Zimbabwean palms, which we looked at first of all, and which have been written about before, I know very little about this family and I am very grateful for notes kindly supplied by Annemarie De Burgh-Thomas on what had been seen in May, with which I have supplemented this account.

Palms are monocotyledons. Like nearly all monocots, they are not capable of secondary thickening. Their flowers are usually unisexual with parts in threes. There are two types of palm – those with pinnate leaves (feather palms) or palmate leaves (fan palms). Although they are generally tall evergreen trees, some are smaller and shrubbier, forming clumps, while others are almost herbaceous or have a climbing habit.

After seeing our wild Phoenix reclinata, we saw Phoenix dactylifera, which is the Date Palm. It has pinnate leaves and shaggy leaf bases. Male and female flowers occur on different trees.

Nearby was an oil Palm, Elaeis guineensis. It has pinnate leaves and is monoecious with male and female flowers on the same plant, although in different inflorescences. It is a tropical species and needs high temperatures all the time to grow well and in those conditions may flower and fruit 3 or 4 times a year.

Although it does grow on the highveld, it never flowers and in our lowveld it only manages to flower once a year. The oil is crushed out of the fruits and is used as edible oil.

Near the Herbarium were some Chamaedorea species. This is a New World genus of some 100 species, extending from Mexico through Central America and into S. America. They are generally small understorey palms of forests. Chamaedorea microspadix, sometimes referred to as the Bamboo Palm, has remarkable bright orange fruits, whereas the others are mostly black. It makes an admirable plant for either indoors or a shady spot. Chamaedorea costaricana and Chamaedorea seifrizii are somewhat similar clumping palms and are also cultivated.

The Red Latan Palm, Latania lontaroides, occurs in the Mascarene Islands, where it is now very rare. However, it is commonly cultivated and has a striking red colouration when young. Near the Herbarium we finally looked at the remarkable specimens of Roystonea (the Royal Palms) with their swollen trunks and at the long skirts of the Washingtonia species.

With so many palms to be seen, we hope to continue next month with more of the same.

Our thanks to Tom once again.

-Mark Hyde

SOUTHERN MATOPOS AND TENDELE RIVER

Early on Sunday morning the 4th May 1997, we set off on the Kezi Road heading for Hendrik’s Pass in the Southern Matopos. It was a lovely day starting off cool and crisp, becoming warm to almost hot at midday. The scenic drive was much enjoyed and we stopped at the Kumalo West turn-off to wait and rally all members of the expedition, making sure we hadn’t lost anyone. Our Chairman not being with us on this occasion lessened the risk I must say, but we will not dwell on that subject.

Cassia abbreviata. Photo: Petra Ballings. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

We found an amazing number of old acquaintances in very short order while we waited. Cassia abbreviata, Combretum molle, Diospyros mespiliformis, Grewia flavescens, Lonchocarpus capassa, Ozoroa insignis, Pappea capensis, Peltophorum africanum, Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia, Pterocarpus angolensis and Pterocarpus rotundifolius, Rhus lancea, Terminalia sericea and Trema orientalis. All trees were in splendid condition after the good rains.

We then continued another 20km or so and stopped for a coffee break in beautiful country with a lot of Pterolobium stellatum still full of red fruits all around us and it really impressed our four American visitors.

We continued along the Shampanyama River and turned sharp right just before the twin peaks of Domboshaba, past the Euphorbia confinalis colony, over the Mwewe and Tendele Rivers to our picnic spot under a large Erythrina latissima, surrounded by splendid views and interesting rock formations.

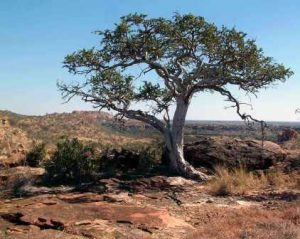

Boscia albitrunca. Photo: Rob Burrett. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Here we climbed over the rocky outcrops and found a host of trees, most of which we knew but also two or three which gave us trouble, not having our fundis with us. Yours truly has spent much time in the Cape this last year, trying to study the ‘fynbos’ of the peninsula and this appears to have had the effect of eliminating some of my memory regarding trees. Anno Domini? Filing cabinet too full? Who knows? However, we did identify over 80 species, which wasn’t bad for the likes of us. We were particularly pleased to find Acacia tortilis, Allophylus africanus, Boscia albitrunca, Crossopteryx febrifuga, Turraea obtusifolia, Vangueria infausta as well as sundry other, better known species.

We had travelled 117km on the way out, 7km more than we needed to, due to male assertiveness (l know where the turn-off is leave it to me). So by the time we had backtracked and had lunch we could only manage one more short walk before it was time to start for home.

On the way home we passed the famous Njelele, sacred mountain of the Matabele, where there are annual rainmaking ceremonies, among others no doubt. Anyway, legend says one does not dare to point a finger at it for fear of dire consequences….

We made one more stop on the side of the Shampanyama River to look at some of the riverine growth as the sun dipped down behind the kopjies. I always enjoy the drive back in the evening light when the bizarre rock formations stand out in enigmatic silhouettes.

-Clem van Vliet.

On the tree list for the Tendele River area and Southern Matopos are: -¬

Acacia arenaria, Acacia galpinii, Acacia karroo, Acacia nigrescens, Acacia rehmanniana, Acacia tortilis, Afzelia quanzensis. Albizia amara, Albizia versicolor, Allophylus africanus, Aloe excelsa, Azanza garckeana, Boscia albitrunca, Bridelia mollis. Buddleja saligna, Burkea africana, Cassia abbreviata, Clerodendrum glabrum, Colophospermum mopane. Combretum apiculatum, Combretum hereroense, Combretum imberbe, Combretum molle, Combretum zeyheri, Commiphora marlothii, Commiphora mollis. Commiphora mossambicensis, Commiphora pyracanthoides, Commiphora schimperi, Crocoxylon transvaalense, Ehretia rigida. Crossopteryx febrifuga, Croton gratissimus, Cussonia natalensis, Dichrostachys cinerea, Diospyros mespiliformis, Diospyros kirkii. Erythrina latissima, Euclea divinorum, Euclea natalensis, Euphorbia confinalis, Euphorbia cooperi, Euphorbia ingens, Euphorbia tirucalli, Faurea saligna. Ficus abutilifolia, Ficus glumosa, Ficus ingens, Ficus thonningii, Flueggea virosa, Gardenia volkensii, Grewia flavescens, Grewia monticola. Hexalobus monopetalus, Olea europaea, Kirkia acuminata, Lonchocarpus capassa, Ozoroa insignis, Olax dissitiflora, Pappea capensis. Parinari curatellifolia, Pavetta eylesii, Peltophorum africanum, Piliostigma thonningii, Pouzolzia mixta. Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia, Pterocarpus angolensis, Pterocarpus rotundifolius, Rhus lancea, Salix subserrata, Schrebera alata, Sclerocarya birrea, Strychnos cocculoides, Strychnos spinosa. Terminalia sericea, Trema orientalis, Turraea obtusifolia, Vangueria infausta, Vernonia colorata, Ximenia caffra, Ziziphus mucronata

SHRUBS:

Barleria albostellata, Cissus cornifolia, Euphorbia espinosa, Euphorbia griseola, Maytenus heterophylla, Pterolobium stellatum, Strychnos matopensis

PARASITES:

Loranthus, Viscum

BIRKDALE PASS 20 April 1997

A rusty sign hidden in a grove of Uapaca alongside the road indicates the start of the Birkdale Pass. Here the Great Dyke with the two lines of rounded hills is faulted and although not easily noticed is offset by nearly a kilometre with the road following the path of least resistance along the baseline of the shallow hills.

The Great Dyke here consists of sparse vegetation, the soft flaky serpentine just below the thin soils being partly responsible for this by providing little nourishment.

Ozoroa longipetiolata. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Only stunted trees survive, albeit the chemically tolerant ones, such as Ozoroa longipetiolata with its distinctive long petiole and the rubber tree, Diplorhynchus is relatively common here. John Cottrill demonstrated with much determination the copious white sap that is contained in the bark of Diplorhynchus. It is worth stopping here for a while to look around for although the variety of species is not great the change in vegetation patterns is really well defined. The stands of Brachystegia on typically highveld granite derived soils ending abruptly where the seams of serpentine with associated chemical activity curve upwards to meet the present land level. In a number of areas irregular lines of Waterberry Syzygium guineense mark the change. On the shallow hillsides occur several of the endemic plant species with the curious Aloe ortholopha being perhaps the best known and first collected in 1926 at the Mtoroshanga pass some 20km to the southwest. The other being Euphorbia wildii – a small shrubby plant with a stem resembling a stretched pineapple.

The dyke streams are crystal clear and flow all year except for the drought period of the early 1990s and consequently few fires venture into this moist riverine as evidenced by some amazingly thick and deeply fissured bark on an Erythrina abyssinica. As has been the pattern this year possibly with the better rainy season, movement through the bush has been hampered by the great masses of thick yellow webs spun by the golden orb spiders. Invariably one gets entangled in these masterpieces finding a large spider resplendent in yellows and black a few centimetres away from your eyes! This is the female, supposed to be non-poisonous to humans and many times larger than her drab mate (makes a change for the ladies in nature to be sporty models!). However, in all happy environments there is always a snag, this one being a small grey unwelcome guest hanging around on the fringe of the web stealing prey; these are one of the many kleptoparasitic spiders – a rather fancy name for a thief.

Further on and within the shallow dolerite hills that run parallel to the dyke a sign advertises a sculpture garden along a narrow rutted road. Time for a lunch stop here before wandering over to see the many and varied greenstone, (a form of serpentine we were lead to believe) ‘sculptured’ objects, some with potential and others with grotesque features guaranteed to induce nightmares. Leaving the enthusiastic individuals chipping away at their masterpieces, a path lead us to another stream and after disturbing some individual bathing in the crystal waters, the society tactfully withdrew and followed another path along an agreeable stretch of riverbank with Rapanea, Cussonia, Mukwa and numerous Brachystegia boehmii.

An interesting day once again with dyke vegetation, spiders and a sculpture garden for variety. Many thanks Rob for arranging this trip for us.

-Andy MacNaughtan

MHOWANI HILLS FARM (Sunday 18 May 1997)

SUCCESSION AND A SORROW TREE.

Ken and Sue Worsley invited us to their garden at Mhowani Hills Farm where Ken is manager. Sue is a trained ecologist with a master’s degree and has worked for National Parks for ten years. It was Sue’s professional background that provided some interesting insights into ecological succession.

ECOLOGICAL SUCCESSION

The acacias were on the flat ground that had previously been cleared for tobacco or some similar crop. The dominant coloniser throughout the country is Acacia karroo but here Acacia polyacantha was the pioneer.

Mines surround the area and the sound of heavy machinery crushing ore was very audible. At Patchwork mine Acacia polyacantha took six weeks to germinate in the fine tailings from the mines slimes dam and tolerated 110 PPM of cyanide used in the beneficiation of the gold. One of the mines was iron ore and it was not known if the other was gold. Acacia sieberiana was the other dominant pioneer.

Both trees have corky bark to withstand fire. Many acacias depend on fire to get the seeds to germinate. The long lush grasses after an excellent wet season would certainly make a magnificent blaze if it were to catch alight much later in the year. The major long grass was a thatching grass Hyperthelia dissoluta, the genus Hyparrhenia was evident and is also used in thatching. The grasses were none of the weed varieties associated with recent cultivation for example nutsedge (Cyperus), common couch (Cynodon), and Eragrostis (love grass), Eleusine (Rapoko grass). The big tall grasses are large seeded and deep rooted. The small grasses are shallow germinators with small seeds. The deep seeding grass would be more fire resistant. The brilliant orange flowers of a tall stand of Tithonia rotundifolia stood out at about a metre and a half high in the brilliant sunshine. Some yellow and white butterflies belonging to the family Pieridae at a glance visited these. Medium sized butterflies with a white or cream base, rounded bodies and brilliantly coloured wing apices. The Pierids are sun loving and congregate on bushes and flowers. The season was almost past and it was drying out to afford more tinder for a magnificent bush fire.

Msasa and Mnondo take up to thirty years to reclaim. There were some Msasa and Mnondo that were a fair size but these trees are more susceptible to fire and were predominantly at the foothills where the grass does not grow so long. The Acacia had very long trunks and were tall and could withstand fire damage once the grass torched. The Acacia polyacantha and Acacia sieberiana were difficult to distinguish apart. Both were tall, corky barked trees spreading their branches on the top and there were no flowers.

For quick identification – Acacia sieberiana has thicker pods, straight thorns and a spine at the tip of the whole leaf, or rachis and not at the end of the pinna bearing the leaflets. The bark is greyish and flowers creamy white highly scented pompoms or balls.

In contrast Acacia polyacantha has thin veined pods, paired hooked thorns and spikelets of flowers, i.e. long tails. The bark is a beautiful white giving it the common descriptive name white thorn.

The rule, which is applicable 98% of the time, is that spiked thorns are associated with pompoms and hooked thorns are on trees with spikes of inflorescences.

The other sturdy pioneer was Dichrostachys cinerea, which is called the sickle bush or Chinese lanterns because of the lovely inflorescence that is pink on top and glowing yellow like a lantern below. The pink portion is composed of sterile flowers and the yellow apical portion is reproductive and is both male and female. The pods are clustered and convoluted. There are no spines or prickles but there is a spine at the tip of the branch. It is very Acacia-like in appearance and belongs to the same subfamily Mimosoideae. It readily encroaches into grassland and in particular that which has been overgrazed. It is an excellent pioneer, forming thickets and giving way to Msasa and Mnondo.

From Kadoma to Gokwe it is the only plant that survives the ravages of goats. Dichrostachys cinerea has been used in recovery of land at Empress Nickel mine. Fencing is stolen from around the mine pits and Dichrostachys has been successfully grown and replaced the need for re-fencing.

There was little evidence of recent incursion by man but changes in the natural vegetation patterns are evidence of prehistoric eras in Zimbabwe. In the tradition of the indigenous people it is used medicinally, as a toothbrush and for fortune telling. Have you ever wondered why the end branches, which fork, have been pulled apart? It is not a coincidence. The twigs are pulled very like a chicken wishbone to give a yes/no answer to a question. None of the end branches had been mutilated and none of the indigenous trees had been used for medicine collection.

Man had been excluded from the habitat for a little while. However, increased mining activity usually results in the denuding of indigenous vegetation. The mining act protects plantations that are normally exotics but not the valuable indigenous trees. Indigenous trees are slower growing and their cultivation does not appear to be an economic proposition. In recent years the alluvial panning of gold has resulted in serious silting of the rivers.

Are we going to see more and more of our natural resources abused through ignorance? Our wanderings brought us to a clump of trees on an anthill. The significance of the trees on the anthill was that these species are less fire resistant and grow out of reach of grass fires. Moisture and nitrates are supplied from the clay-like soil of the anthill. The trees were not the focal point of interest.

One of the ornithologists had spotted a White-faced Owl in a Pappea. The little bird had been disturbed from his slumber. The eyes were half closed and the eyelid was drawn to exclude the sunlight. The pair of slit-closed eyes resembled sucked treacle toffees. The owl momentarily blinked at the intrusion and flashed a pair of orange round eyes that were hurriedly closed. The head was pulled back at right angles to the body and sleep continued uninterrupted. Most birds sleep in that position and not with their heads under their wings. These were drawn out in long trusses and the white and black streaks tufted upwards. The grey and black broke up the body shape and the little owl was concealed. There was a distinct black shield around the eyes. Otus leucotis prefers to rest in the bigger trees and usually in pairs but there was no sign of a mate. The call of the White-faced Owl is a bubbling b-b-b-b-bhoo sound and not the classic ‘too wet to woo’ or maybe it was too young to woo.

THE SORROW TREE, PSOROSPERMUM FEBRIFUGUM.

PSOROSPERMUM FEBRIFUGUM. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

It was remarked upon that the Psorospermum is never cut down which is correct because it is associated with tradition. To cut the tree for firewood would cause strife in the home. The tree is prized for its medicinal properties and the bark is gathered with care not to ring-bark. The tree is revered by older people and in the previous liberation struggle leading to the formation of the state of Zimbabwe; parents would take their troubles to the tree. It was a place of focus and contemplation. Very often an offering was placed at the foot of the tree as supplication but not in the belief that the tree had a spirit. Most of us who are Christians call it the Christmas berry because it fruits with bright red berries at Christmas. We should remind ourselves that we too tie gifts to a tree all be it seasonal.

The only people who weep at a time of war are the mothers on both sides. Today we fight a different war against an enemy we are unable to defeat. Many people are dying in the AIDS pandemic. Today a common sight is when a body is conveyed to the rural area for burial a red cloth is tied to the vehicle. On a visit to Warren hills area looking at ground orchids the writer came upon a Psorospermum with four pieces of red cloth neatly knotted together and tied around the trunk. The significance was unknown to me and I felt I did not wish to pry on another person’s tribulation but to walk away and respect the tree had a very special meaning for another cultural group. The derivation of Psorospermum means a scurfy seed and febrifugum means to free from fever. It is reputed to cure fevers. Incidentally the name is pronounced ‘sorrow’ with a silent ‘p’.

-MARY TOET.

TREES AND OTHER PLANTS OF DAVID LIVINGSTONE’S ZAMBEZI EXPEDITION 1859-1963

Continued from Tree Life No 208 June 1997.

MOWAWA: 3 June 1860: “fine tree called Mowawa grows here.”

This was written on the middle Zambezi upstream of the Cabora Bassa rapids in the region now covered by the lake. The species was Khaya nyasica, red mahogany, known in Shona as mubawa or mawawa. It is nearly always a fine tree, wherever it occurs, but the most famous specimen is the Big Tree of Chirinda Forest near Chipinge.

MPUAPUA: 5 December 1858: “Mpuapua, gum-bearing tree.”

This was written on the Zambezi, just above Tete, on Livingstone’s return from an exploratory excursion to the Cabora Bassa rapids. Mpuapua is not readily identifiable for there is no easily accessible publication on vernacular names of Mozambican trees. The closest is mpwapwa, one of the Malawian names for Oxyanthus speciosus, a small tree of evergreen montane forests in the highlands of Malawi and Zimbabwe. It is not gum bearing and would not be found in the Zambezi Valley.

NTENE: 5 December 1858: “Ntene, name of species of Nux vomica, the pulp between seeds of which are tasted like strawberries.”

Livingstone’s English is not at its best in this passage, but the meaning is clear. He was on the Zambezi near Tete at the time, and was obviously referring to a species of Strychnos. As a medical doctor with a good botanical knowledge, Livingstone would have known that the old-fashioned heart stimulant, Nux vomica, was obtained from the seeds of the Indian tree Strychnos nux-vomica and he evidently applied the name Nux vomica to other Strychnos spp. as well.

The subject of this journal entry was possibly Strychnos madagascariensis, which is known to the Tonga people as muteme, a name close to Livingstone’s ntene.

OCHRO: 14 February 1859, in Kirk’s enclosure to Dispatch no.13: “By the banks we observed tobacco, Indian hemp, ochro and pumpkins seemingly uncared for.”

This was written in the Shire Valley and the “ochro” mentioned here, was probably ochra, Abelmoschus esculentus (formerly Hibiscus esculentus) known in Shona as derere, derere rechipudzim, gusha, gusha rechirungu, manhimbo and nyatondo and in Ndebele as indelele.

The species came originally from tropical Asia and has been cultivated widely for its fruit, which is cooked as a side dish or used in soups and gravies. The Arabs or Portuguese probably introduced it.

OLIVE: 24 August 1859: “Got some pieces of ebony and one of olive wood as fuel.”

At the time Livingstone was on the Shire River and the fuel was required for the steam launch. The olive referred to here would have been Olea europaea ssp. africana, and much too beautiful a wood to be burnt in a ship’s boiler! The Shona names for the wild olive are mupfungo or mupfuri, and the Ndebele name is umnquma.

PALM: 27 September 1861: “The Palm tree which yields the oil of commerce, or a smaller species of it, found here. The nuts are not half the size of those on the West coast.”

This was written during Livingstone’s boat journey up the western shoreline of Lake Malawi, some distance to the south of Nkata Bay. If Livingstone was correct in his identification, the palm tree he saw was Elaeis guineensis. None of the palms occurring in Zimbabwe produces oil.

PAPYRUS: 10 November 1861, in Dispatch no.5 to Lord John Russel:

“Before reaching the lake proper” (i.e. Lake Malawi), “we pass through a lakelet called Pamalombe…. it is fringed with a broad belt of Papyrus, among which so much malaria and sulphuretted Hydrogen gas exists that the white paint on the bottom of the boat was blackeded” Papyrus is Cyperus papyrus, a tall tufted sedge that was used by the ancient Egyptians for making writing paper.

-Lyn Mullin To be continued.

ANDY MACNAUGHTAN CHAIRMAN