TREE LIFE 517

SEPTEMBER 2023

Greetings all, by now you will know that Rob Jarvis has stepped down from being Vice-Chairman on the committee and being the editor of this newsletter – Tree Life. Can’t keep a good man down – best wishes for the future Rob.

Fortunately with a bit of arm twisting, (I only had to break one arm!) Linda Hyde has agreed to become the new editor. However, as she is so busy at moment at Reps Theatre with the forthcoming Pantomime, I will be filling in a bit as temporary editor.

Temp Ed – Tony Alegria

Bridgeways Complex Tree Outing 22nd July 2023

by Tony Alegria

Present on a warm Saturday afternoon was our host Ann Sinclair and the rest of the ladies being Dawn Siemers, Teig Howson, Lorraine Regadas, Marina Mason, Kassy Robbie and her friend Charlotte. The guys were Jan van Bel, Stuart Wood, Jim Dryburgh, Vic Gifford and me.

On arrival at the complex, I went to the mystery acacia and collected some specimens for Mark Hyde to identify. When I reached the venue, I just parked behind all the other vehicles which at the end of the outing became a bit of a problem with much manoeuvring to get everybody out. Teig was the last to arrive and she had to reverse a long way.

Mystery acacia – Acacia nilotica???

By the time I reached our host, she was already showing the gathering various trees she had planted over the years she has been resident there. She explained that this area had been a gum tree plantation and over all the years she has lived there the gum trees have gradually been cut down till very recently the last of them was removed. Ann has planted mainly indigenous trees over the years and the Faidherbia albida and Erythrina lysistemon were particularly large given that they were only about thirty years old.

There were two exotic fig trees with many roots above ground which must be a nightmare for those mowing the lawn. Although they looked similar, one had small red figs (Ficus benjamina var benjamina) whilst the other had bigger yellow figs – Ficus benjamina var nuda.

Ann had planted many Dovyalis caffra trees, close to her home, that she had obtained mostly from the Bulawayo area but unfortunately no fruit has ever been produced as all the trees are male – yep, not a single female tree amongst them! However, some of the others she had planted elsewhere within the complex were female and had produced fruit which makes a delicious tarty jam.

Some of the other trees seen: Dombeya rotundifolia; Acacia nigrescens; Acacia sieberiana; Acacia robusta subsp. clavigera; Fernandoa abbreviata; Rhamnus prinoides; Pappea capensis; Diospyros lycioides; Diospyros whyteana; Combretum imberbe; Combretum molle; Oncoba spinosa; Podocarpus falcatus and what could be a Podocarpus henkelii.

We looked at a Caryota urens, Fishtail palm with a single trunk which had inflorescence between the fronds and compared it to the other fishtail palm which grow in clusters (Caryota mitis) and produce inflorescence from anyway on the trunk from low down (knee height) right up to the fronds. These are the only palms I know of which have twice pinnate leaves.

The outing ended with tea and “buns” supplied by our host, thanks for a wonderful afternoon, Ann.

National Botanical Garden tree walk Sat 5th August 2023

By Tony Alegria, photograph by Bart Wursten

On a sunny cool morning only six members turned up for a morning of botanizing. Only two ladies came – Ann Sinclair and Zia Thomas. The guys were Jan van Bel, Jim Dryburgh, Mark Hyde and me. The mission for the day was to look at newly exposed trees that can now be seen since the undergrowth has been cleared and are now visible.

Right at the car park is a rather huge Searsia natalensis and Xeroderris stuhlmannii. On the way to another area we came across a couple of Kigelia africana. Sausage trees which were just beginning to flower right next to a Ficus bussei which had very few leaves but was absolutely laden with fruit.

The next place of interest was a cleared undergrowth section which now allowed us entry under some big trees was where the Erythrina latissima. Broad-leaved coral-tree lives. Although the “lucky bean” tree had no leaves or flowers, we are very keen to keep an eye on in the hope of seeing the big leaves and hopefully flowers in the near future.

Diospyros nummularia

Also on this small rocky outcrop were several Diospyros nummularia. Granite jackal-berry, one of which had a black label with white writing saying it was a Diospyros natalensis subspecies nummularia so this is a name change with these trees now becoming a species.

Whilst in this area we demonstrated how to locate a tree by using the GPS location. Once you get to the spot, now you really have to look around as the tree you are looking for can quite easily be anything up to 10 metres away. We did locate the Dalbergia nitidula. Purplewood dalbergia we were looking for than found that there were a few more than we had previously seen.

The last area we visited was the High-Altitude Rainforest and Forest Margins which has also had the paths cleared and are now accessible, this is where we looked at the Juniperus procera. African juniper. In Zimbabwe only one specimen has ever been seen in the wild. Its natural habitat is the evergreen mountain forests and it is an important timber tree in Kenya.

More on the Screw Pine (Pandanus utilis)

By Mary Toet

This is a follow-up article to my first article, The Screw Pine, which appeared in Tree Life number 495 of November 2021.

Description

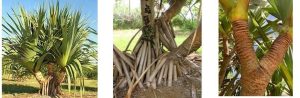

Screw pines have palm-like leaves with spiny margins and midribs. These are produced in tufts at the branch tips in three or four close twisted ranks around the stem, forming the screw like helices of leaves that give the species its common name of Screw pine. See Figure 1. The next two pictures show (Figure 2) the prominent prop roots and (Figure 3) a section of the stem showing the corkscrew like spirals.

Figure 1: Photo: Wikipedia Figure 2 Figure 3

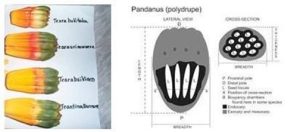

Figure 4: Pandanus: polydrupes

Propagation

Propagation is by seeds and stem layers. On plants, stem offspring are constantly formed, which (if possible, with aerial roots) are separated and rooted at a soil temperature of at least 20 °C. The seeding process begins with soaking in water for five days, and on average, it will germinate after two months of seeding.

Fruit (see Figure 5)

Figure 5: Fruiting tree, Dandaro. Photo: Mark Hyde

Pandanus spiralis produces tough fibrous fruit. Each cluster of fruit has about 10 to 25 individual nut-like fruits which each contain 7 to 10 seeds. Indigenous people eat the fruit once they have ripened to a deep orange-red colour. The fruits are eaten by monkeys and birds. The seeds are protected by a mesocarp and strong endocarp.

The prop roots

The Pandans are in the fore front of the tidal zone. The prop roots are massive and hydroscopic obtaining moisture from the sea spray and rain. They develop from the upper parts of the stem creating an ecosystem within a larger ecosystem. As the tide recedes the monkeys salvage fruit while Fiddler crabs feed on the remains of dead fish that have been stranded by the receding tide. When the tide turns, they retreat to their holes and block these with their large red claw.

The prop roots grow vertically down into the soil and can replace the main stem. Stilt roots are short and horizontal supporting the screw pine against the monsoon winds and neap tides. While the neap tides can wash away the soil, the screw pines remain, nor are they blown away. Information from L. Jeebit Singh.

The old prop roots have furrows sending water down to the soil and the prop roots store water.

Damage to the tips of the prop roots where water is stored can result in the death of the pine. The tips have a meristem where the cells are constantly dividing and producing new cells. These cells have a single set of chromosomes found in vegetative tissue. The reproductive cells have a single set of chromosomes prior to fertilization. The propagation by seed and by prop roots is however, so successful and so invasive that it is considered to be an ecological threat.

Local observations

Around Harare most of the pines are male and formed from vegetative growth. At Dandaro Retirement Village near Borrowdale, Harare there is a female pine which in 2023 had been fertilized. The brightly coloured seeds (Figure 6) had been shed leaving an orange receptacle (Figure 7).

Distribution

Pandanus species originated in Queensland, Australia and now are found throughout Africa and Polynesia. The Pandanus has commercial value, the strong fibres made from the leaves are used to make ropes and baskets.

Ed’s note: Pandanus utilis can be seen very close to the Herbarium at the National Botanical Garden

Figure 6: Seeds at Dandaro. Photo: Mark Hyde Figure 7: Fruit receptacle Dandaro. Photo: Mark Hyde

A trip to the Great Dyke, 11-14 July 2023:- Part 1

Text and photos by Ian Riddell

Chikonyora Hill with old chrome mine workings in the serpentine rock

From the 10th to 15th July I participated in a bird survey of part of the Umvukwe Range of the Great Dyke, the section from Mpinge Pass to the Suoguru fault gap (on map Chikonyora 1630D4). This was a most interesting and jolly damn cold(!) expedition to an area that I’m sure everyone, or nearly everyone, has only ever driven past on the road north from Mvurwi, although looking at the QDS results on the Flora of Zimbabwe website shows that some collecting has been done from Mpinge Pass itself. It is worth pointing out that the Pass has slightly different flora and structure – the flanks of the dyke are eroded on both sides and this deposition has greater better soils and taller trees. The fault line here also allows tree roots better access and there is more water.

The photo above shows Chikonyora Hill with old chrome mine workings. Serpentine of the Upper African Surface with a predominance of Protea spp. below the pyroxenite crest of the dyke. Samples of serpentinite saprolite from outside the collapsed chromite workings are enriched in nickel (probably mainly in nickeloan serpentine and goethite).

The Mpinge section doesn’t seem to have been geologically or botanically covered as well as the northern and southern sections. Barclay-Smith (1964) covered the northern end of the dyke south to the Suoguru gap and Proctor & Craig (1978) surveyed the vegetation associated with mineralised soils in the Mutorashanga Pass area; there are other publications covering these areas, too, but the Mpinge section is a gap worthy of filling. Useful geophysical information was found in Geological Society link in the references.

The dyke is a well-known geological formation of ultramafic and mafic rocks, bounded by granite on both sides, with important mineral ore deposits, particularly chrome and nickel. The pyroxenite or norite hills support savannah or woodland type vegetation and the serpentine hills or ledges are open with grassland or open wooded grassland. About 70% of the dyke has serpentine soils. This distinctive serpentine vegetation is thought to be due to a very high exchangeable magnesium/calcium ratio and also to nickel toxicity, whilst the pyroxenite and norite are not toxic to plants.

The interesting feature of the serpentine are the herbs, geophytes and succulents; there are 6 endemics only found in the northern section of the dyke. These were all new plants for me.

Despite this being a bird survey, a bit of botanising was inescapable! However, I overlooked a lot, noticing some familiar plants in passing, so there is much still to document. I noticed a Dierama-like herb, for example, but it was dry and hopefully a revisit in the wet season will reveal its identity (Dierama doesn’t occur here).

Thanks are given to Bart Wursten, Mark Hyde and others, who identified or confirmed species on iNaturalist, where I uploaded my records.

Day 1: 10th July

The team arrived on the early morning flight from Johannesburg but delays in getting the equipment through customs, and then some shopping, meant we only got to our lodge at Mvurwi much later than hoped. The recce we intended didn’t happen but I squeezed in a short birding walk through fallow farmland and degraded miombo while the others caught up on some sleep.

Day 2: 11th July

We two birders set out in the dark and chilled pre-dawn for the Pass and onto the dusty dirt road passed Mupingi Smelter, a name I’d only seen on maps.

This took us through the soil-mining areas and the mill and slimes dam of the old Mpinge eluvial chromite operation dating from the 1970s. I take it that mining this area has restarted, leading us into devastated serpentine where the surface was scraped up for chrome extraction. Finding the way through this wasteland was a bit tricky – or rather, finding the track for the way out!

Eluvium or eluvial deposits are those geological deposits and soils that are derived by in situ weathering or weathering plus gravitational movement or accumulation. The process of removal of materials from geological or soil horizons is called eluviation or leaching (Wikipedia) and it is in this shallow layer that the chrome is found. I have to wonder if land rehabilitation is written into any lease or contract? The future sheet erosion and siltation of streams is depressing to contemplate!

A view to the west flank of the dyke. The bare red areas in the middle ground are surface-stripped serpentine.

We eventually relocated the track and followed it passed the skirts of Chikonyora, arriving at a convenient spot to start our first transect. This was a combined recce/survey so we were feeling our way and didn’t know where the tracks went or the lay of the land.

Stepping out of the truck at just before 7 a.m. was a rude shock; the strong and freezing wind was immediately felt in stinging and burning hands! My fleece couldn’t cope so I was relieved when my confrère produced a windbreaker he had brought from Jo’burg. That set the pattern for the rest of the trip – windcheater on all day, gloves for most of the time and a beanie all day; too cold for a hat, which meant a slightly sunburnt face.

Right by the truck was Dyschoriste trichocalyx subsp. verticillaris, a glandular herb with light blue-purple flowers. We were probably on the serpentine ecotone and we headed over a small ridge with light miombo to the steep western edge of dyke, negotiating the debris from cut trees. This was our first introduction to the rampant tree cutting that is going on in the area and, it later became apparent, explained all the tracks!

The miombo was thicker here with a lot of Brachystegia boehmii so we were off the serpentine. Amongst the rocks were Aloe cryptopoda, Dr Kirk’s Aloe and a Striped Pipit. Heading southwest along the edge we searched for a way down. Finding what looked like the least hazardous route near some scolding Lazy Cisticolas we earned our klipspringer badge on a very rocky precipitous descent, a Familiar Chat awarding the prize at the bottom. Less welcome was a large ring-barked msasa (African Grey Hornbills and Yellow-throated Petronias confirmed we were in miombo woodland) and further down the slope a patch of chopped Brachystegia boehmii, but we were now in farmland.

Ozoroa longipetiolata

It was much warmer and sheltered off the dyke on the leeward side. Just before we crossed a small dry stream was an endemic Great dyke raisin-berry Ozoroa longipetiolata. At the powerline after the stream we turned northeast, following the base of the dyke for some 800m.

At a Woodland Dogplum Ekebergia benguelensis we veered off the powerline to a gorge that led us back up the dyke. This was a beautiful riverine fringed stream that was running strongly but I didn’t list all the species though there was Phoenix reclinata and, if I recall correctly, Englerophytum magalismontanum and Syzygium.

Coniodictyum chevalieri on Ziziphus mucronata

Cliffs formed on our left and right as we climbed higher but there was some sort of path or game trail to use on the right side of the stream. A small Buffalo thorn Ziziphus mucronata had Coniodictyum chevalieri, a fungus previously believed to be very rare, forming galls. However, I have seen this previously at Crowborough and Mukuvisi Woodlands. It is an endemic disease of Ziziphus mucronata.

Around this time, I suddenly realised that my sunglasses were gone. They hadn’t been very securely perched on my beanie. After a few steps back down the path I decided a hunt would take too much time – who knew where they had been snagged whilst ducking and diving under bushes. If anyone should chance across a baboon wearing sunglasses on the dyke, tell him I want them back!

Cyrtorchis praetermissa

Heading further up the narrowing stream looked increasingly difficult but the steep face on the south side looked doable. Along the ascent were Aloe cryptopoda, Euphorbia griseola subsp. mashonica and some Sansevieria. Brachystegia glaucescens grew on the slopes. Coniodictyum chevalieri on Ziziphus mucronata.

Back on the dyke we headed to the vehicle. What was interesting was that the track crosses two small streams through the wooded grassland above the gorge. The first one is just on the edge of the drop-off and both were quite dry. An exploration would no doubt reveal a strong spring in the top of the gorge feeding the stream. We headed back to Chikonyora, hoping to find the rest of our party.

Below the south face of the hill we saw their vehicle and espied them higher up a spur, carting equipment to the meteorological mast. So up we went, entering miombo woodland on the ridge. This is described as the wooded ferruginous silicified zone of a well-developed silica cap on the broad Upper African mesa extending 3 km to the north (whence you come to the Suoguru gap). The soils are very shallow and rocky and the miombo is consequently short – quite reminiscent of the dwarf miombo of Nyanga.

I don’t recall seeing such an orchid load in miombo as appeared here, testament to the eastern side of the dyke catching moisture-laden prevailing winds through orographic effects. The Hidden Bird Orchid Cyrtorchis praetermissa was widespread on Brachystegia spiciformis, clumps fallen to the ground in many places.

Lichen on rocks – who can name the rock?

On the way back down I diverged off the path to investigate the big glaringly white patches on the rocks. These were lichens but I would really like to know if anyone can identify the fascinating rock they were on.

Convolvulus randii in flower

Globimetula mweroensis mistletoe was on Velvet-leaf Vangueria vestita (Tapiphyllum velutinum) and Protea sp. was a dominant genus on these slopes. The Neddicky was a common bird in the serpentine hills and also by the vehicles was Convolvulus randii. Bart commented that ‘This used to be Convolvulus ocellatus var. plicinervis, which is a Great Dyke endemic in Zimbabwe. It has now rightfully been given full species status under the name C. randii. A Neddicky was nesting high up (for this species) in the lowest branches of a Violet Tree Securidaca longepedunculata. The trees growing on serpentine looked a bit odd and I couldn’t quite place them at first but small ones were quite common along the track to the west of the hill.

https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:266845-1’)

Kalanchoe possibly luciae.

We had our ‘pad kos’ and retraced our route, passing our morning stop and explored wood-cutter tracks looking for a fixed viewpoint for bird observations. Walking up from chopped miombo on the eastern edge we passed through serpentine and climbed 90 m up to miombo on a hilltop. In the grassland a Kalanchoe growing in rocks might have been luciae.

Our afternoon O.P. was unproductive, bird-wise, so I sought out some plants. I misidentified some orchids on a very dwarf msasa but Bart corrected them to a Tridactyle sp. and Polystachya sp. I shall remember that Polystachya has pseudo-bulbs and hope to catch it flowering on another visit. The Ivory carpet Leptactina benguelensis subsp. pubescens grew in patches in the rocky soil.

We were on a spur that was separated by a 700 m wide valley, over 100 m deep, with a view onto the dwarf miombo on the main ridge. Two prominent trees stuck up over twice the height of the canopy and these intriguing anomalies will be dealt with later. 1.6 km to the south we watched the progress of one of our teammates, slowly climbing the met mast, dragging up a cable and microphones, an arduous task. Like a tiny spider in the wind, this took hours!

In the late afternoon we headed down and by chance noticed a rough track that climbed the hill so we followed it back to the junction of the track we had come in on. Another wood-cutters’ track but it proved easier to drive on (in 4×4) than walking up to the ridge in the days to come.

To be continued.

References

Barclay-Smith, R.W. (1964). Report on the ecology and vegetation of the Great Dyke within the Horseshoe Intensive Conservation Area. Kirkia 4: 25‒33.

Proctor, J. & Craig, G.C. (1978). The occurrence of woodland and riverine forest on the serpentine of the Great Dyke. Kirkia 11: 129‒132.

Wild, H. (1965). The flora of the Great Dyke of Southern Rhodesia with special reference to the serpentine soils. Kirkia 5: 49‒86.

https://www.geologicalsociety.org.zw/atlas/mpinge–section–%E2%80%93–exposures–upper–african–surface–chikonyora–hill

Tree Society Committee and Contacts

Chairman Tony Alegria tonyalegria47@gmail.com 0772 438 697

Honorary Treasurer Bill Clarke wrc@mweb.co.zw 0772 252 720

Projects Jan van Bel jan_vanbel@yahoo.com 0772 440 287

Venue Organiser Ann Sinclair jimandannsincs@zol.co.zw 0772 433 125

Tree of the Month Ryan Truscott ryan.kerr.truscott@gmail.com 0772 354 144

Secretary Teig Howson teig.howson@gmail.com 0772 256 364

Tree Society Website https://treesociety.org.zw/

Tree Society Facebook https://www.facebook.com/groups/ztreesociety/

Flora of Zimbabwe: https://www.zimbabweflora.co.zw/

Flora of Tropical Africa: https://plants.jstor.org/collection/FLOTA