TREE LIFE

JULY 2023

Hi Everyone,

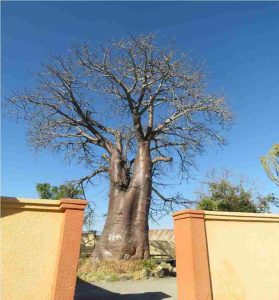

Herewith another Tree Life with some interesting articles to pique your interest. Above is a magnificent baobab growing literally a stone’s throw from a mountain that peaks at 2 100 metres above sea level. We recently visited an area along the lower Gairezi River in north-eastern Zimbabwe that can be approached either by driving up through Rusape, Troutbeck and thence down through the Nyamaropa Valley until you find the last range that the Gairezi breaks through in its quest to reach the sea. Or you can go via Mutoko, turn right at Nyamapanda, cross the Rwenya River on the new bridge and after about 100 bone-rattling kilometres you will be there. The baobabs are magnificent and a few are featured in this newsletter.

Cheers, Rob Jarvis, Editor

MAFUNGAUTSI PLATEAU THIRD DAY:

The quest for the fossil trees: by Jan van Bel

After the very exciting and endless recording of trees yesterday, which had people retiring to bed early, it was a wonder that everyone was already up at 6 am to start another excursion. By 7 am we were all queuing in front of the breakfast room and waiting for our names to be called out to go and receive our plate. Staff had improved their system so that the process went a whole lot faster than the day before. We had our English breakfast and by 8 am we were on the road.

Today we hoped to see some tree species which should grow around here but had eluded us yesterday. To begin with, our gurus were still looking for the Acacia (Vachellia) luederitzii, which is at home in the Kalahari sands. So we drove in convoy back through Gokwe centre to the national parks office to pick up some park wardens. One of them was going to show us a spot where we could possibly find our elusive luederitzii. We went deeper into the Mafungautsi National Park and parked at a large building from the Parks officials. The weather was perfect again, not too hot nor cold . It was very dry so that the park’s name didn’t do itself justice (Mafungautsi : a misty place). We parked under an old Baphia massaiensis, jasmine pea, with a very contorted and prostrate stem. We were now getting quite familiar with this tree species after seeing plenty of them yesterday.

We followed our warden over a well-maintained path through a forest with an interesting variety of trees of which the oldest and highest ones were msasa. Arriving at the tree that the warden pointed out we saw Meg, who was dropped there by car, negotiating her way with her ambulator to station herself under it. We were now at the border of a dry vlei where 4 or 5 of the same acacia species were growing. Not many other species were seen there. Counting pinnae and leaflets and looking at the thorns and the pods that did not look like any in the books, no conclusive identification could be arrived at. Most features pointed in the direction of sieberiana species. Being quite familiar with Vachellia sieberiana, maybe the most common acacia tree around Harare, the pods of these acacias in this spot were curled to very curled, while we know the sieberiana to have straight pods. Thickness and size, colour and weight were all as expected of a sieberiana pod. We found some hooked spines besides the mainly long straight spines. The presence of these 2 types of spines could point in the direction of luederitzii species, but our tree here had more pinnae than the books mention. So after a small hour, we still couldn’t conclusively name it. Maybe Mark and Meg will expound on this.

Next on the program was the quest for the fossil forest. Named for the petrified logs from the Triassic age (some 220 million years old) that can be seen lying there. So we went back to the cars and started driving through tight paths with trees and shrubs brushing the sides of the cars. The slow pace for negotiating these paths allowed us to do some drive-through botanising, picking leaves through the windows. We were still hoping to find the Grewia retinervis with its reticulate veining, which has its home here in the Kalahari sands. We also wanted to see more Strychnos pungens and here there were many. Yesterday we only saw one. This Strychnos pungens, spine-leaved monkey orange, has remarkable bluish-green fruits and a spine at the leaf apex. We now were very familiar with Paropsia brazzeana, after our initial discovery yesterday. These bushes now appeared everywhere. An Acacia, (Vachellia) gerrardii, grey-haired acacia here was also not recorded yesterday.

We then stopped at the side of a vlei where Mark spotted some interesting shrubs next to a patch of Senna didymobotrya, peanut butter cassia, with its ostentatious display of yellow flowers. After some more driving, we stopped again on the side of a big forest. Our guard wanted to show us a huge mukwa tree which proved to be an impressive Burkea africana, wild syringa . It was now lunch time and people started putting out camping tables and chairs. After our lunch, everyone started ambling around without much direction.

Fossilised, hollow log and friendly butterflies at lunchtime. Photos: Rob Jarvis

Cathy, our mushroom specialist, came back with a few dry mushrooms. Even Meg with her ambulator was negotiating her way through the brush. Peter meanwhile was still studying the map to find the best way to get us to the fossil forest.

On the road again over sandy paths between Mopani, Acacia, Parinari and Lantana, we still had to go a long way. The road was now wider and we were driving over undulating sandheaps reminiscent of the dunes along the coast. The fine sand was now making the driving slippery. At one time having to go back and forward several times to be able to pass a broken-down vehicle.

It was late and we were wondering if this long trip with all that bumping up and down was going to get us anywhere at all.

Arriving at a small growth point, with a few shops, we went off the main road and were directed by some locals to follow a path a little further. Getting stuck after a few meters and seeing no paths, we had to turn back. A second inquiry directed us to go back to the main road and proceed a little further before turning off.

It was now getting critically late, considering the bad roads we still had to negotiate to get to our lodgings where they were preparing dinner. Not trusting the directions we were given by the locals, we decided to abandon our quest. We waited for Rob and Sheila who had been in front to turn back. After 15 min. still no sign of them. It was now 17.35h and we had to turn back. Luckily there was a shorter road to get back and we arrived at our lodge at 19.30h.

Braai meat was waiting on the grill and proved to be already too dry. But with a big bottle of beer and being very hungry, no one complained. Rob and Sheila (they also had Ryan in their car) had arrived 15 min later and told us they had found the fossil logs. They showed us the pictures they took. Their absence had everyone worried, so we were happy to see them, but now being tired we also felt jealous of their success and a bit stupid also for having abandoned the quest only half a km too early.

Our local guide who showed us the fossilised forest. Photo Rob Jarvis

The Tree Society took advantage of a visit to Prince Edward School’s Arboretum to witness the planting of a tree by Dorothy Wakeling. Dorothy used to work at the school for many years. Present at the function were a number of members of the Tree Society, including Kevin Atkinson, former pupil and Headmaster of Prince Edward. Now retired, he went on to head St George’s, probably the absolute arch-rival school to Prince Edward.

Dorothy Wakeling looking queenly

The late Queen Elizabeth planted a tree nearby when she visited in 1991. We thought Dorothy looked quite Queenly for the occasion.

Kevin Atkinson with the memorial plate dated 11 October 1991

Trees in the Arboretum

Rothmannia manganjae

Tree with Hamerkop’s nest

The Arboretum had some absolutely beautiful trees, soaring to the heavens themselves. The fact that they were planted on Class 1 red-clay loams with plenty of run-off from adjacent school buildings and a leaky faucet, ensures that moisture is not a limiting factor. In the main area where we concentrated our tree identification, the trees were a good 20 meters tall, full canopy over the grassed area underneath and in the fork of one, a pair of hamerkops have made their nest for several years.

However miscreant schoolboys had either removed or mixed up some tree labels and the Society intends to return with a dedicated team to map and record the exact positioning of all the trees in the Arboretum.

INSECTS FOUND ON THE LEAVES OF A RAIN TREE AND A FIG,

ARBORETUM, PRINCE EDWARD SCHOOL, HARARE, ZIMBABWE

by Mary Toet

The Arboretum at Prince Edward School was very interesting because it had been neglected and the trees were left to grow undisturbed, these trees were spectacular giants. An arboretum is a plot of land where trees and shrubs are grown for study or display The trees had grown to unexpected heights in competition for the sunlight. The girth of the trunks was over a metre in diameter. There was dead wood that had not fallen from the trees. It was apparent that pesticides had not been used. It was an ecological paradise for insects.

The area was enclosed and preserved against browsers. There was a copious supply of underground water. The soil was red and clay-like and could hold micronutrients.

The visit was in June close to the Solstice and cold. Some night time temperatures were in the single digits. The tree leaves were covered in dust because they were situated next to a busy road. The leaves were old and leathery. Insects require warmth to live and breed, and soft new leaf tissue for feeding.

Clay soils are rich in minerals and these are held by the clay and not leached, Clay soil provides a foundation to anchor the roots. The roots can withstand extreme temperatures and moisture.

Ptyelus grossus or spittle bug: – photo from Kloof Conservancy, The Leopard’s Leap

There were no live insects but evidence of their existence was found in their remains of hard exoskeletons in frass of webs and excreta produced by the insect larvae. An exoskeleton contains chitin and broken pieces of chitin stimulate the plant’s immune system so that they produce calcium for strengthening cell walls and are not so prone to insect attack. The frass contains micro-organisms that help aerate the soil and break down organic matter to release micro-nutrients.

All these conditions were excellent for tree growth. We examined a rain tree, Philenoptera violacea and a fig tree. Philenoptera violacea has a little bug Ptyelus grossus that appears two weeks before the rains. The tree is special and revered as a forebringer of rain. Ptyelus sucks sap and exudes quantities of water.

The Spittlebug nymphs are protected by bubbles blown with their excretions.

The soggy existence of spittle-bug nymphs: photo from Kloof Conservancy, The Leopard’s Leap

There are insufficient nutrients and sugar in the sap so it has to process quantities of water, leaving puddles on the ground. The spittle bug causes it because it has an opening above the anus that can take in air and when the abdomen is squeezed, the air is pumped into the escaping water forming a frothy mix which gives protection to the developing larvae. The mouth parts are piercing stylets that go through the bark and into nutrients in the foam. Information from Moira FitzPatrick and Coates Palgrave.

A tiny caterpillars found feeding in one of the windows transparent areas or windows which were light brown in colour

Interesting were the leaves of the rain tree. The leaves were three lobed and it appeared that every leaf on the tree had been attacked. The action of tiny caterpillars feeding on both layers of the leaf produced a transparent area or window light brown in colour. A very small caterpillar was found in one of the windows. It was still alive but confirmation of its identity would depend on seeing the adult. All these lesions went no further than the midrib. Meg Coates Palgrave suggested the thin skin was probably a leaf cuticle that made a strong cover and protection for the developing larvae.

Diplorhynchus condylocarpon is commonly called the Horn Pod Tree because of the two horn-like spines on the pod. It is a small tree sometimes reaching 20 metres with a trunk 2 metres in diameter. The tree in the Prince Edward Arboretum was much larger. The tree produces abundant inflorescences of flowers that are attractive to butterflies, bees, birds and spider mites. It is a browse plant and it is a favourite browse plant of the black rhino.

The tree is important to man and is said to cure indigestion, diarrhoea, fever, snake bites, infertility and venereal disease. The wood is used for sanitation against certain species of maize pests. Maize is a staple diet and economically important. The wood can be burnt, and the smoke is used to fumigate the maize crop in the field. The Lepidopteron caterpillars are eaten and would be a source of protein in the diet.

Ecologically insect pests will find a niche on the tree. Some of the pests recorded include spider mites, Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) and sometimes termites. There are difficulties for tree colonizers because of the rough fissured bark and latex.

Insect pests are found at the start of the wet season when growth is new, soft and contains nutrients. The insect pests, mites, and termites have stages in their life cycle called instars some have four phases e.g. adult (imago) egg, caterpillar or nymph which is the feeding stage and a pupa or chrysalis. Adaptations for surviving the dry or cold weather include the adult finding a safe warm place, the nymphs can go underground on the roots or branches of trees. Referred to by Meg Coates Palgrave as the underground forests of Africa. The cicada can spend 17-19 years underground. Once the adult emerges it has to find a mate. For this purpose, it has a large tympanum that it vibrates to produce a characteristic high-pitched loud sound.

On one of the leaves there was frass trapping a pale adult butterfly or moth. It had a characteristic spine protruding from then last abdominal segment. There was no camouflage colouring suggesting it was nocturnal and a moth. On the underside of midrib of the leaf there were long lesions that were brown and hard but had not closed. Towards the apex of the leaf where the midrib was narrow there were no lesions The midrib was raised and would be big enough to support a moving larval form, Numerous lesions showed that more than one caterpillar had used this route. A supply of sugar and nutrients in the phloem would be available to sustain the migrating larvae. The underside of the leaf is a protection from rain, sun and predators.

The potato tuber moth Phthorimaea operculella is of economic importance in Zimbabwe. It is a major pest attacking underground tubers It will also attack other solanaceous plants like tobacco. Once it finds an area to mine on the midrib it builds a silken web around the area. The moth is nocturnal but does have camouflage markings of black and brown patches.

The moth found on the leaf of Diplorhynchus has a similar life cycle and made the lesions on the midrib.

A pale adult butterfly or moth

An adult or imago was found trapped in the frass. It was a moth or butterfly. Probably a moth because it would be protected from birds. The pale whitish colour had no markings to disguise it on the bark of a tree. It had the characteristic long spike from the last abdominal segment.

An egg was found attached to the underside by a fine piece of web. This was on the underside of the web of the leaf where the cuticle was not so thick. The developing larvae would not get washed off by rain or dried out by the sun,

Moths are a pest of many economically important trees in America.

A baobab thriving 30 years after it fell

THE BAOBABS AND FRIENDS OF THE LOWER GAIREZI VALLEY

Photos and text by Rob Jarvis,

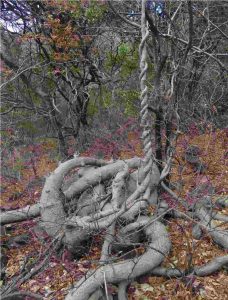

A highly twisted Fockea

Tree Society members would be well advised to stay in their cars when approaching the area from the Nyamapanda side. Demining is taking place 40-plus years on! The baobab above is thriving more than 30 years after it fell. And Fockea, left, just defies logic.

The MAQ Zimbabwe company, removing the landmines from this area

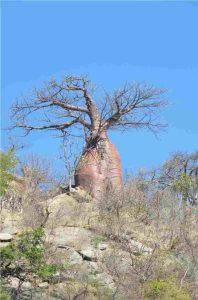

A baobab, pink with the exertion of trying to extract non-existent moisture from the granite.

Baobabs of every shape, colour and description were in evidence in the lowveld environment on the approach from the Nyamapanda side. A bottle left growing on solid rock and pink with the exertion of trying to extract non-existent moisture from the granite.

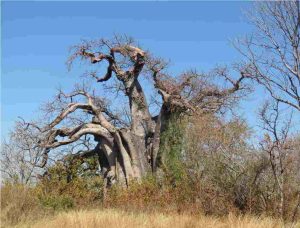

A truly “upside down tree”

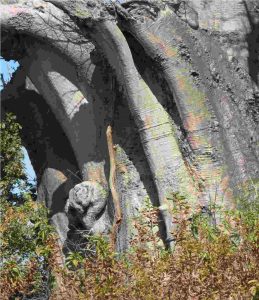

The giant flutes of the baobab

Above right and below, left, this tree was undoubtedly what Mr Adansonia himself would have called an upside-down tree, with roots up-ended and clawing in the fresh blue air, looking for soil! This particular specimen had just the most magnificent trunk rising in giant flutes from the hot dry scrabbly soil. Many is the tale it could tell of life on the edge!

And below right, on the way to Nyamapanda, is this gateway to fine dining at the Mutoko Hotel, which is itself perched upon a once-bare granite dwala. I remember this tree from the 1970’s when we used to frequent the bar in Mutoko when passing through that part of the World!

The gateway to fine dining at the Mutoko Hotel

TREE SOCIETY COMMITTEE AND CONTACTS

Chairman Tony Alegria tonyalegria47@gmail.com 0772 438 697

Vice Chairman Rob Jarvis bo.hoom52@yahoo.com 0783 383 214

Honorary Treasurer Bill Clarke wrc@mweb.co.zw 0772 252 720

Projects Jan van Bel jan_vanbel@yahoo.com 0772 440 287

Venue Organiser Ann Sinclair jimandannsincs@zol.co.zw 0772 433 125

Tree of the Month Ryan Truscott ryan.kerr.truscott@gmail.com 0772 354 144

Secretary Teig Howson teig.howson@gmail.com 0772 256 364

Tree Society Website https://treesociety.org.zw/

Tree Society Facebook https://www.facebook.com/groups/ztreesociety/

Flora of Zimbabwe: https://www.zimbabweflora.co.zw/

Flora of Tropical Africa: https://plants.jstor.org/collection/FLOTA

A totally biodegradable bark boat

And we leave you this month with a picture of a totally biodegradable bark boat, plying its trade between Mozambique and Zimbabwe, across the Gairezi, absolutely unfettered by officialdom. No licences, no border post, no taxes for fuel, no cost in extracting metal or other ores, no exorbitant cost for passports, just one tree every decade or so being stripped of bark and bound together with folds and natural ropes. Purpose-built and they only charge for crossing if you are very fat or if the river is raging! Cheers!