TREE LIFE

September 2020

![]()

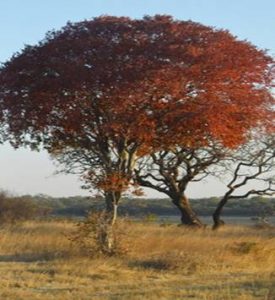

It is the time of year when we should be looking forward to going out and revelling in the beauty of the “spring” and enjoying, generally, the change of season. There can be few sights more breath taking and awe inspiring than a magnificently shaped msasa in all its spring finery.

We still have nothing to report and no exciting outings to look forward to!

This Tree Life contains an article relating how a de-forested piece of land in Costa Rica was restored to its former glory. A further article by Meg Coates Palgrave on Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration and another by Clare Griffiths on the work being done in Western Hurungwe. All these make for interesting and encouraging reading during these days of mass de-forestation here and world wide.

Our Tree of the Month, Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia, another favourite and so spectacular at this time of year, but what the emphasis is in this delightful story from Ryan is the importance of instilling the love of trees in the young.

It is encouraging to see the various Posts on our Tree Society Face book page of tree planting projects and other related articles creating an awareness of trees amongst our rural school children.

It would be good, if those members who happen to read Tree Life, and who know of, or hear of, encouraging tree planting or tree preservation projects being undertaken around the country to either Post these on our Face book page or make the Tree Society Committee aware of these projects so we can Post them.

Ian Riddell has again provided brilliant photographic evidence of what is happening deforestation wise right within our National Parks!

Keep Safe

-Mary, Editor

Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia

As I drive around Harare, I try to imagine what indigenous trees could replace some of the exotics growing in the city’s gardens. Like this month for instance, when the Lady Chancellor trees, Citharexylum spinosum, have turned a glowing and eye-catching orange.

What local species would be a worthy substitute? The answer must surely be the Kudu-berry, which is our tree of the month.

Winter-time and early spring is the Kudu-berry’s time to dazzle. Its leaves, which hang like small medallions, have turned a vivid amber.

The Kudu-berry, also known as the Duiker-berry, has a special place in my heart. Its scientific name — Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia — was the first one I memorized as a boy. It was June, 1987, and my brother and John, his swimming coach, had come to visit.

John was more than 40 years my senior, but we shared an interest in history, and he became a good friend. John had grown up in the very same house as me, near Mutare, in sight of the Mutarandanda Hills whose lower slopes are blanketed with indigenous trees, including Kudu-berries. It was during that visit that John gave me my first tree book: Common Trees of the Highveld, by RB Drummond and Keith Coates Palgrave. He also encouraged me to learn Latin names, starting with two of the most difficult.

One was Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia; the other was Bequaertiodendron magalismontanum, the Stem-fruit. These became our code names. He’d send me updates via the post on his latest historical research, addressed to ‘PM’, and signed ‘BM’.

All these memories came flooding back when I took my family on a visit to Harare’s Haka Park this month. From our picnic site we had spotted one particularly glorious Kudu-berry, and my eight-year-old and I walked across the park to get a good look at it.

“It looks like its leaves are on fire,” she remarked as we stood beneath it. She was right, and the fruit, said to be the food of antelope, are also beautiful: perfectly spherical and peppered with tiny white dots.

I remember John telling me that he picked up one of these berries on a walk in the bush and kept it for months inside a silver mug on his mantlepiece. One quiet evening, while he was reading in his sitting room in Harare, the fruit capsule exploded with a sound like a gunshot.

The bark is another distinctive feature, often cracking into almost perfect rectangular segments, and the trees are, as Drummond and Coates Palgrave mention, “shapely, with good crowns and straight boles.” All in all its attributes are equal to that of the lovely Lady Chancellor. But it has something more.

The Kudu-berry my daughter and I had looked at in Haka obviously made a deep impression on her. A few days later I looked inside her English composition book, and there was her sketch of the tree, with its fiery crown, and an account of our walk to see it.

Thirty-three years after John first introduced me to this strikingly beautiful species with its tongue-twisting Latin name, I marvel at how it is able to capture the hearts and minds of the next generation.

Ryan Truscott

THIS COUNTRY REGREW ITS LOST FOREST. CAN THE WORLD LEARN FROM IT?

Pedro Garcia nurses a plate of seeds on his lap. “This is my legacy,” he says, tenderly picking up the seed of a mountain almond — a tree which can grow up to 60 meters (200 feet) tall and is a favoured nesting spot for the endangered great green macaw..

Aged 57, Garcia has worked on his seven-hectare plot, El Jicaro, in northeast Costa Rica’s Sarapiqui region for 36 years. In his hands it has turned from bare cattle pasture to a densely forested haven for wildlife, where the scent of vanilla wafts through the air and hummingbirds buzz between tropical fruit trees.

Garcia has restored the forest — home to hundreds of species from sloths to strawberry poison-dart frogs — while also cultivating agricultural products from pepper vines to organic pineapple.

This makes him self-sufficient but it does not turn a profit. Instead, Garcia relies on ecotourism — he guides biologists and ecologists around the plot for a small fee — and payments for ecosystem services (PES), a scheme run by the Costa Rican government that rewards farmers who carry out sustainable forestry and environmental protection..

Garcia is one of many Costa Ricans who have powered a mass conservation movement across the tiny Central American country. While most of the world is only just waking up to the importance of trees in battling the climate emergency, Costa Rica is years ahead.

“It is remarkable,” Stewart Maginnis, global director of the nature-based solutions group at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), tells CNN. “In the 1970s and 1980s Costa Rica had one of the highest deforestation rates in Latin America, but it managed to turn that around in a relatively short period of time.”

Costa Rica is the first tropical country to have stopped — and subsequently reversed — deforestation. Can the rest of the world follow its lead?

When Costa Rica lost its trees

In the 1940s, 75% of Costa Rica was cloaked in lush rainforests. Then the loggers arrived, chainsaws in hand, and cleared the land to grow crops and raise livestock. While there is ongoing debate about the extent of reduction, it is thought that between a half and a third of forest cover had been destroyed by 1987.

Soon after this all-time low, the government took a series of radical actions to convert the country back into a natural paradise. In 1996 it made it illegal to chop down forest without approval from authorities and the following year it introduced PES.

Today almost 60% of the land is once again forest. Cloud forests envelop the country’s mountain peaks, thick rainforest lines the beaches of the south and dry forest sweeps the northeast. This rich landscape is home to around half a million plant and animal species.

But the country’s reversal is in stark contrast to the rest of the tropics, where deforestation rates are soaring. In 2019, tropical regions lost almost 12 million hectares of forest, according to data from the University of Maryland – equivalent to 30 football fields a minute. Nearly a third of that loss occurred within older, carbon-rich primary forests.

Other countries have made ambitious commitments but “if restoration is only replacing losses from ongoing deforestation, then it may be better than nothing, but it’s a bit of a Band-Aid,” cautions Maginnis.

The money motive

Costa Rica’s success is underscored by economics. It paired its ban on deforestation with the introduction of PES, which pays farmers to protect watersheds, conserve biodiversity or capture carbon dioxide.

“We have learned that the pocket is the quickest way to get to the heart,” says Carlos Manuel Rodríguez, Costa Rica’s minister for environment and energy, adding that people are more likely to take care of nature if it provides an income.

Elicinio Flores was 22 when a government scheme granted him a 10-hectare plot of land in Sarapiqui. When he arrived in 1976, it was “untouched,” he says.

“There were no paved roads, no access to drinking water. It was difficult because you couldn’t make a living from the forest then,” he tells CNN.

Working with neighbouring families, he cleared the trees and created open pastures divided by fences, where cattle now graze on dusty grass.

But in the middle of his farm, Flores decided to preserve a five-hectare pocket of original forest. Despite occupying a small area, it’s a dense and tangled jungle — walk into it and it’s hard to believe there’s agricultural land on all sides.

Flores has since expanded his forest, replanting two more hectares of trees with help from the PES scheme, which pays an average of $64 per hectare per year for basic forest protection, according to FONAFIFO, the nation’s forestry fund.

The scheme allows farmers to generate additional income by selectively harvesting timber from the reforested areas. Flores seeks guidance from Fundecor, a sustainable forestry NGO, to ensure he only fells trees that are not vital to the ecosystem.

Timber sales have helped pay for his eldest daughter’s university studies in sustainable tourism. “I feel proud when I walk through the forest, not only for me but for my whole family,” he says. “When I am no longer here, I know that my children will continue to look after it.”

The government scheme, which is financed predominantly by a tax on fossil fuels, has paid out a total of $500 million to landowners over the last 20 years, according to FONAFIFO. It has saved more than 1 million hectares of forest, which amounts to a fifth of the country’s total area, and planted over 7 million trees.

Eco-friendly culture, ecotourism hotspot

According to Maginnis, Costa Ricans’ deep respect for nature has played a vital role in the country’s reforestation success. Its culture is summed up by the national motto, “pura vida,” which is used as a greeting, a farewell and in many other social contexts.

While its direct translation is “pure life,” “pura vida” signifies much more than that — both a gratitude and a peace with oneself and the surrounding environment.

This respect is reinforced by the country’s booming ecotourism sector says Patricia Madrigal-Cordero, former vice-minister for the environment.

“People come to see the mountains, the nature, the forests, and when they are stunned by a monkey or a sloth in the tree, communities realize what they have here, and they realize they should care for it,” she tells CNN.

The nation of 5 million people welcomes around 3 million visitors a year. According to its tourism board, more than 60% choose Costa Rica for its nature, with many flocking to the country’s national parks – which, alongside other protected areas, cover more than a quarter of the country’s land mass.

Last year, tourism generated almost $4 billion in revenue for the country. The industry accounts, both directly and indirectly, for more than 8% of GDP and employs at least 200,000 people.

“People in Costa Rica receive a lot of money because of tourism and that changes the incentives of land use,” says Juan Robalino, an expert in environmental economics from the University of Costa Rica.

While neighbouring countries have similarly stunning landscapes, they attract far fewer tourists, he says. In 2018, Nicaragua, a country more than double the size of Costa Rica, welcomed less than half the number of tourists.

Without the tourists, communities put less effort into preserving the environment, says Robalino. This creates a downward spiral – with less revenue, funding for conservation drops, which leads to less ecotourism.

A model country?

Other countries do not necessarily lack environmental will. Guatemala, Mexico, Rwanda, Cameroon and India are among those that have committed to restoring at least a million hectares of forest through the Bonn Challenge, a global effort that aims to restore 350 million hectares of degraded ecosystems and deforested land by 2030.

But these countries lack Costa Rica’s long history of environmental policy coherence and consistency, says Maginnis.

It is this combination of political will, environmental passion and tourism that has enabled the country to become a pioneer in reforestation.

Rodríguez, the country’s environment minister, says that while Costa Rica’s basic strategy could be applied anywhere, “principles and values” need to be in place too. These include good governance, strong democracy, a respect for human rights and a solid education system, he says.

The secret to Costa Rica’s success is its people, adds Madrigal-Cordero. “We have created peace, pura vida” she says. “Nature is in our DNA.”

Nell Lewis, CNN

Drone footage courtesy of Danny Cordoba / Fundecor

THE “MY TREES” OR “MITI YANGU” PROJECT, HURUNGWE, part 2

Back again, here I am, a month later to complete the story that I started in the last newsletter, and it has been an extraordinary month. I do urge, if you have not read the last Tree Life, do so as my story leads directly on from where I left off and is intricately woven into the narrative of the other articles.

It must be asked, are we to be optimistic about the outcome of this endeavour, and in fact other reforestation endeavours worldwide? Absolutely, there are many tales of success and here are two well-known examples from which I will draw a few points and what they have in common that have contributed to their success, things that other reforestation drives could draw from and emulate.

- Large scale dreams are possible – South Korea embarked on a reforestation drive at the beginning of the 1960’s since when the total timber in the ground there has risen from 31 million cubic meters to 164 million cubic meters in 1984 and now more than 17 billion trees have been planted and South Korea is nearly 75% clothed in forest. This project was initiated by a government that asked the people what they wanted and asked how they could achieve it together. People were capacitated to achieve the task and given ownership of the challenge.

- More locally, the Green Belt Movement started in Nairobi in 1977, has seen the cooperative work of women in a band across Africa growing indigenous seedlings, and planting for reforestation, for woodlots to provide non-timber forest products in a tapestry that reflects their needs and desires for an environment that they wish to restore for their children. The green belt extends across the continent with the vision that it will ultimately join the west coast to the east coast in a green ribbon. Different areas have dealt with different degrees of success but see for yourself on google earth there is indeed impressive evidence of success in many areas. The areas that have been remarkable in the land rehabilitation are proudly stewarded and cared for by the peoples living there. Those that are less successful are well understood.

Successes, where they exist, in both of these camps are owed to a balance in the four components necessary for a project to succeed. Those components include financial capital, knowledge capital, physical capital and human capital. The first three are self-evident. Projects will absolutely fail if too much or too little money is thrown at it, the sweet spot of just enough must be sought. We need to gear ourselves up with the knowledge required for the actual task and not settle on a generic concept that does not deal with our lands diversity, our peoples diversity. We need to ensure that the physical space, water and soil components exist.

More important, however, than these three, I have found that investment in human capital is key. Indeed, more than 70% of failed reforestation projects are shown to be the result of insufficient time being invested in people, in understanding their needs, their dreams for that area and their challenges. Projects that leave residents thinking that they need you or me, and that communities don’t have the ability to effect change, will ultimately fail. We must acknowledge that we are a cog in the works and that we all have a part to play. Additionally, it is important to understand in a community how different relationships work. If I am to work in an area I need to know if the land tenure is malleable or fixed in a way that I understand so that I can align my input to that. Most important, I have come to understand that it is probably a universal truth that NO-ONE wants to lose trees in the area they live. If trees are being lost there what are the challenges facing people there and if I intend to be part of the solution how can I be part and not a prescriptive overlord of the situation.

Again, as before, I asked what people wanted and what they could do and where they wanted their tree nurseries to be and how could I help. We had settled on sites, trees and I had asked the community to gather 15 kg of seed to commence our work. On returning a week later to the lake to commence making the first nursery there, I was presented with over half a tonne of seed by the community who kept arriving with more and more seed and offers of land on which we could work together – in the community’s words “basa rakakura’ –the task is big.

This last month has been extraordinary. I had been asked to come and help establish nurseries in ward 24 of Hurungwe, much hotter, lower, drier than ward 8 and after the regular presentation of a goat to the Chief, meeting the community leaders, most of Deve community met by the dam and we talked.

Realising the enormity of what lies ahead is indeed critical, we are not running a 100m race, we are running a marathon. We need the endurance. Fortunately, we know it will take time, time that will allow is to build a relationship, acknowledge a common goal, pass on what I have learnt to the huge depth of rural understanding and endurance. Ultimately failure is not an option.

I end with this chaotic picture of two men whom I believe are on the edge of an epic narrative but with the first of 15000 chaotically filled bags of soil about to have my need for order about to be added and a communities’ dreams for shady groves. Watch this space-

Yes I am optimistic.

-Clare Griffiths

WOODLAND REGENERATION: PART TWO

FARMER MANAGED NATURAL REGENERATION – FMNR

I have been advocating managing regrowth in indigenous woodland for about 25 years, but it is much easier to enthuse people into planting trees. And then someone discovered FMNR on the internet. Now it is official, now it has a name! Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration and even an acronym FMNR.

“The first principle is that very often the woodland is already there, but it is under ground and we simply need to give it a chance to get established “.

That I can endorse. I visited a farm which 23 years previously had stopped growing tobacco. Some lands had been left fallow and were now woodland, albeit quite young, except along the edges which had regenerated more rapidly. When ploughing to cultivate crops the depth is probably not more than 30 or 40 cm and tree roots go well below that, just sitting waiting to shoot again. not even all the pesticides etc. used on tobacco, kills them all off.

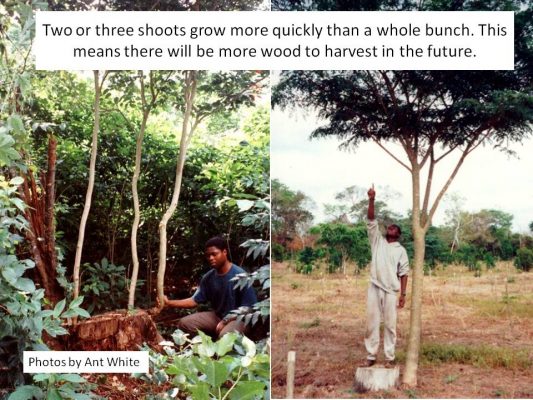

“The second principle is that selective pruning and thinning of this regrowth is very beneficial for the growth and the form (shape) of the trees.”

“The third principle is individual and community engagement. It requires agreement to a set of rules developed and agreed to by the stakeholders themselves; it is facilitated by enabling policies such as the right for individuals and communities to benefit from their work, through legal harvest of the trees and tree products (fruit, honey, medicine…).”

Without the active involvement and decision-making of the community it will not work.

By all means plant trees, but don’t remove any natural growth, that might appear.

A hole has to be dug, compost and water procured and brought to the site and added when the tree is planted and then there is the post-planting care. Despite all the care and attention, the tree might have, it does not always survive for various reasons including the lack of the root-fungus. And often the care and attention is inadequate.

Pruning is easier than planting and the root system is already present.

All but the three strongest stems are cut away and the twigs are cut away for half their height. The leaves are put at the base as a mulch to keep in any moisture, the rest of the leaves are set aside to go on the compost heap, and the twigs and sticks for fire kindling.

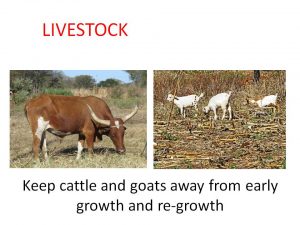

Two big threats to regenerating and mature forest and woodland. Protection is needed against both livestock and fires

FMNR started in Niger. FMNR is now practised in Uganda, Kenya, Sudan, Australia that I know of.

WHY NOT IN ZIMBABWE before the land looks like the picture on the left

-Meg Coates Palgrave

FYI – the losing battle to preserve miombo! Firewood at Chivero chalets, in Chivero National Park – some big trees. And on the north bank water development vehicle piled high with miombo, no doubt also cut in the so-called protected area.

-Ian Riddell

HOW TREES PROTECT THEIR LEAVES FROM BROWSING ANIMALS

Trees have various mechanisms to protect their leaves from being browsed. Trees communicate within a species to warn other trees that they are being eaten. An interesting book entitled “Do Trees Talk to Each Other” Wuhllebun describes what happens when a giraffe starts chewing on an Acacia. The tree notices its leaves are being chewed and emits a distress signal. The signal is a gas ethylene. The neighbouring trees detect the ethylene and react in the same manner.

There is a form of crowd protection. If this does not stop the browsing, there is enough tannin to kill a large herbivore.

Plants further protect the leaves by making them fold. This mechanism has been extensively researched. One is the sensitive plant Mimosa pudica, a prostrate or straggling annual or perennial herb up to about 1 m high, sometimes with woody stems near the base. Amongst many authors this is described by H.S, Panil et.al (2007) in the Journal of Bionic Engineering. When Mimosa pudica is touched the leaves fold up upon themselves and the stems droop. The folding is rapid and the leaves are reduce to as much as 15 to 25 per cent. It is hypothesized the herbivores and insects will not eat the plants because the leaves are smaller and look wilted. This also has the effect of exposing the sharp spines on the rachis. These leaves do not look appetizing and they have become loaded with tannins.

A description on how the folding mechanism works is in an article in Plant Ecology entitled “Leaf folding of sensitive plant shows context dependent plasticity” (Amalir-Verghs, 2009). Motor cells on the one side of the pulvinus (extensor cells) lose their turgor pressure upon stimulation. As a result, the flexor cells on the other side of the pulvinus thicken. Simply explained in terms of osmosis. It is reminiscent of mammalian muscles relaxing and contracting. Interesting is that leaves close at night because there is no photosynthesis and this is done to prevent water loss. There are no bees pollinating so pollen loss is prevented by the folding leaves (Bourget, 2019).

The mopane tree, Colophospermum mopane, sometimes known as the turpentine-tree, shows the same mechanism. This is the dominant tree over large tracts of comparatively clay-rich soil areas with a low rainfall and occasionally loosely associated with miombo. The turpentine is a complex cocktail of terpenoids, alkaloids, tannins, glycosides. The gas is a deterrent for browsing animals and alerts surrounding mopane trees.

To summarize, some plants, show an arsenal of anti-browsing adaptations. The folding and drooping of the leaves, exposure of spines and increase in tannins. Tannins in the bark protects the trees from bacteria and fungi.

Wohllebun says trees connect through underground fungal networks. Trees share water and nutrients through the networks and communicate to send distress signals about disease and drought. These fine like hair tips of trees join together to make up a microscopic network. Fungi consume about 30% of the sugar produced by the tree. The fungi in return release nitrogen, phosphorus and other nutrients that are taken up by the roots. Further supporting Wohllebun, there is an underground method where the fungus mycorrhiza transmits information along contacting roots (Smithsonian Magazine).

It is sometimes very necessary for game and livestock to be able to browse on plants in arid conditions. Cattle can tolerate up to 5% tannin in their fodder. There are chemicals that bind tannins. Polyethylene glycol, PEG contains sufficient oxygen molecules in a long chain to form hydrogen bonds with the phenolic and hydroxyl groups in the tannins. The tannins are bonded to the PEG and pass out with the faeces. In this manner greater amount of tannin can be consumed. The chemical ecology of tannins plays a critical role in controlling pathogens and worms in herbivores (Chemistry Epon (2017). The FAO reports that cattle can consume tree foliage with tannin. It is probably a matter of balancing the amount of tannins consumed using PEG and to leave sufficient in the diet to be beneficial.

(This or something like it, known as Browse-Plus, is probably what was put in the drinking water troughs in the Lowveld during the 1991/92 drought enabling the cattle and game to eat more browse)

Just a note: We humans consume tannins in our tea, red wine and beer. The consumption must be beneficial but not in excess.

-Mary Toet

Mimosa pudica is native to South America and an introduced weed in Africa. The indigenous sensitive plant is Biophytum umbraculum, an annual up to 40 cm high, which we have seen during visits to several venues around Harare.

Chairman – Tony Alegria