TREE LIFE

March 2020

Your committee is reconsidering the Subscription rate. In last month’s Tree Life it was stated that the subscription for 2020/21 would be RTGS100. To a lot of our members this amount is unattainable on top of all the other daily increases we are facing. Our biggest expense is our social duty of paying for the fumigation of the absolutely priceless collection of plants in the National Herbarium. As we all know funds are unavailable for this type of essential maintenance from the source where it should come from and so, for some years now, the Tree Society members, because of our vested interests in this collection and because we know the scientific value of this collection have paid for the twice yearly fumigation at the National Herbarium. This has been able to be paid from member’s subscriptions with, sometimes, some help from member’s donations towards this cost. However, the quotation for the fumigation of the National Herbarium plant collection is now beyond Tree Society’s old budget and so at the last Committee Meeting it was decided to put up the subscription to RTGS100. Discussions with various members revealed that they thought this was an excessive increase. We are now reconsidering the matter; we are negotiating with the fumigators and also considering setting the Subscription Rate at RTGS50 for all members, together with an appeal to those members who feel so inclined, to give an additional amount towards the fumigation costs.

As mentioned above, the plants stored at the National Herbarium are beyond valuation, they are well maintained by the dedicated staff working at the Herbarium and it would be really good if we, as members of the Tree Society, could continue to do our bit towards preserving this priceless collection.

Please let us know your feelings on the above, by the next issue of Tree Life a decision on the subscription rate will have to have been made.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tree Society Outings

At a recent Committee meeting there was much discussion about the Tree Society outings every month, and it was decided, for a number of reasons, that from March 2020 onwards there would be only two organized outings a month.

There would continue to be the Botanical Garden walk on the 1st Saturday of each month, this is a venue which will always be of interest, every month there is something new and exciting to see.

We would then organize a 4th Saturday of the month afternoon outing every other month.

The 3rd Sunday of the month outing would then happen every alternate month also, i.e. one month there would be a 4th Saturday afternoon outing and the following there would be a 3rd Sunday of the month outing. These would continue to be advertised in Tree Life, on the Facebook page and on the Website and members would be sent a reminder a few days before each outing, as is being done at present.

The fuel situation, the declining attendance at our outings and the difficulties of finding suitable destinations for these outings are the reasons for this decision and we sincerely hope that members will continue to support and enjoy these happy, informative jaunts to places of interest.

Please remember that non members are always welcome, so bring a friend, or two, to enjoy a time of escape from the everyday hassles in some lovely garden or bit of bush. We will continue to try to organize the outings to venues as close to town as possible because of the fuel situation.

We look forward to seeing you soon.

07 March 2020, 08:30-10:00. National Botanic Garden, Harare outing. We will look at whatever may be in flower and whatever else looks interesting. Join us for a 1.5 hour walk, we will start at 08:30 a.m. from the usual place – the car park. Non members are very welcome to join this pleasant and informative walk, so bring a friend, or two, but not your dog.

15 March 2020, 10:00-12:30. Bushman’s Rock outing. We will meet at the gate and proceed to the Polo Pavilion to begin the walk. You are very welcome to bring your picnic lunch and cooler bag and enjoy a picnic at this delightful venue. This should be a most interesting outing and guests are very welcome to join us, but please no dogs.

For those wanting to share transport, meet at Mukuvisi at 09:00 a.m. to leave at 09:15 a.m.

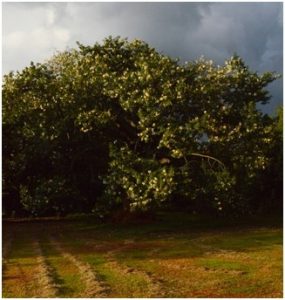

TREE OF THE MONTH — ‘BIG BANG’ TREE OF THE BOTANIC GARDEN Ceiba insignis,

Ceibia insignis in full flower. Photo: Ryan Truscott

Finding inspiration to write Tree of the Month in February is daunting. Everything seems uniformly green, apart from the African Flame Trees, Spathodea campanulata and I’ve already written about them.

To overcome my writer’s block, I decided to visit the National Botanic Garden. But apart from a few sparse flowers on a Silver Raisin, Grewia monticola, there was nothing that caught my eye.

As my daughter clambered up into the branches of the Giant Forest Fig, Ficus rokko, I examined a nearby Fringe-leaved terminalia (Terminalia gazensis) and did marvel at the silver lining around each of its leaves.

But could it qualify to be Tree of the Month? I had hoped to find something more in the line of charismatic megaflora, the botanical equivalent of an elephant or a rhino. The Ficus rokko, perhaps?

Ceiba insignis flower. Photo: Ryan Truscott

My daughter clambered down the tree and once more took up the dog’s leash. As luck would have it, Tango tugged her towards the herbarium.

I followed them and just as we emerged from the garden’s Euphorbia section, I saw it: a tree that stood in awesome splendour in the mid-afternoon sun, with a dazzling crown of white and yellow flowers flecked with pink.

This, I thought, must surely be our Tree of the Month. I went over to look at the label on its trunk. “Chorisia insignis, Tropical South America.”

Ceiba insignis spines. Photo: Ryan Truscott

I felt momentarily unsure about allowing an exotic tree to trump our indigenous ones for the title and also about giving recognition to yet another tree from the genus Ceiba. Chorisia insignis is now known as Ceiba insignis. A year ago, I wrote a story about its close cousin, Ceiba speciosa, the Brazil Kapok.

But this individual tree really did deserve the accolade for lighting up the gardens in an otherwise drab month. Indeed, the tree’s specific name is apt: ‘insignis’ is Latin for conspicuous or remarkable.

Ceiba insignis bark. Photo: Ryan Truscott

From a distance one might even be excused for mistaking it for a Baobab, Adansonia digitata. It has a thick bulbous trunk and what botanists call digitately foliolate leaves (like fingers on a hand). And like the Baobab, its profusion of showy flowers is meant to attract bats.

Bats pollinate C. insignis, also known as the Yachan, in its native Peru and other regions of western South America.

The flowers are huge, with stamens protruding from the petals ready to daub the bats with pollen grains when they come in search of nectar.

Ceiba insignis, leaves. Photo: Ryan Truscott

Scientists studying bat pollination refer to trees like this as “big bang plants” because they produce flowers in such great quantities over short periods.

A 2017 study in the journal Annals of Botany noted that in two big bang species monitored (including our tree’s Central American cousin Ceiba pentandra) pollen was broadly distributed on the bats’ bodies. “Old World bat pollinators rarely hover and probably crawl across clusters of flowers during foraging,” it said.

The flowers aren’t the only remarkable feature of C. insignis. Its trunk and branches bristle with large cone-shaped spines that look big enough to defend it against a foraging dinosaur.

Alas, the spines aren’t able to ward off the ravages of time, and the specimen in the botanical garden appears to be nearing the end of its life. The great trunk is hollowing out, and at its base I noticed large mounds of termites — those vultures of the insect world that perform the essential task of devouring dead and decaying plant matter.

But if this month’s spectacular show of flowers is anything to go by, this grand old citizen of the garden will go out with a bang, and not a whimper.

Ryan Truscott

National Botanical Garden walk, Saturday 1st February 2020

A group of 14 gathered in the car park of the Harare Botanical Gardens on a beautiful clear sunny day.

The absence of rain is of concern and we would rather have seen some meaningful clouds. With Tony leading and Mark and Meg providing much depth of knowledge it proved to be a very interesting morning.

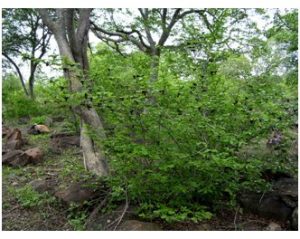

Combretum celastroides a dense straggling shrub grows by the car park. It grows in dry woodland on rocky slopes, the leaves are thin and leathery. They have small dots visible with a 10 x lens on the upper surface, the under surface has scales which give the appearance of skin dotted with a white ball point pen.

Many trees planted in the Garden that were listed in 1970 are no longer to be seen as they have died. There are also trees which have been difficult to identify as planting records are long since unavailable, for instance, along the path is a Millettia species which has not been identified.

Further along the path, a wet patch indicated the presence of spittle bugs in a Spathodea campanulata, the Flame Tree from Kenya.

Ficus cyathistipula is not indigenous and has large brown stipules wrapped round the base of the leaves.

The substance anthocyanin is present in young red leaves and protects the leaves from the hot sun.

Burttdavya nyasica, belonging to the Rubiaceae is a handsome tree and has flowers in spherical balls.

By the tearoom is a tall Albizia versicolor, the poison pod Albizia. The leaves are twice pinnate and very large, and there is a gland on the petiole.

Cordyla africana the Wild mango was heavily in fruit with ripe fruit on the ground. The fruit is a large yellow ovoid drupe. It turns yellow after falling to the ground and is rich in vitamin C. It is edible but leaves leave an unpleasant after taste.

We then looked at Cordia ovalis, Sandpaper Cordia which has very rough leaves which are almost circular in shape. There was a parasite, Loranthus sp. in the tree.

Commiphora merkeri bark. Photo: Mark Hyde

Commiphora merkeri has a ringed bark and is known as the Zebra-bark Commiphora. The Commiphora family has trees with simple leaves some with pinnate leaves and others that are trifoliate.

Trees which lose their leaves for a long time have green bark which can photosynthesize when the tree is bare. Commiphora caerulea is an example of this, with a smooth succulent looking greenish blue bark with brownish papery peel.

We then wandered into the commercial section to see the Tung oil tree from China, Vernicia fordii. The oil extract is used in paint to preserve wood. It dries quickly and is used as a water resistant finish for boats.

The extract, dihydromyricetin, from the Japanese raisin tree (Hovenia dulcis), is used to make herbal infusions. The species Jatropha curcas grows in poor soil and has a deep tap root and lives for 50 years and has potential for producing biodiesel.

The forest Ordeal tree, Erythrophleum suaveolens has twice pinnate leaves, the leaflets are alternate and end in a single leaf. There is no gland on the petiole.

Hexalobus monopetalus has fine glands with citrus oil which give it a nice fresh smell.

Grewia flavescens has yellow flowers and the leaves are symmetrical, other Grewias are often asymmetrical.

Monodora junodii. Photo: Colin Wenham. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Monodora junodii is a small tree from hot dry woodland areas. The flowers are very striking, reddish brown to wine red and pendulous. We collected a fruiting branch with a round mottled grey green fruit about 5 cms in diameter. Under this tree was a sea of wild Zinnia, Tithonia rotundifolia.

Manilkara mochisia, the Lowveld milkberry. The wood provides termite proof fencing poles.

Galpinia transvaalica has shiny opposite leaves, grows up to 6m in height and is a multi-stemmed shrub or small tree. The stems are often crooked and the branches lie low.

In the shade was a dainty Senegalia (Acacia) erubescens with drooping leaves. This can grow tall in sunny areas.

Acacia schweinfurthiana has white balls of flowers and hooked thorns, just to confuse the pattern of straight thorns and flowers in balls and hooked thorns and flowers in spikes!

Thank you to Mark, Meg and Tony for a fascinating morning.

Ann Sinclair

Saturday afternoon outing to Greenwood Park

Only four of us went to Greenwood Park for the afternoon outing on Saturday 25th, January. Present were Jan, Mark, Ryan and myself. With Mark’s help, Jan and I had spent some time in 2017 identifying and labeling the trees on behalf of JCI (Junior Chamber International). In total we labeled 79 trees using the same numbers as seen at Mukuvisi Woodlands and the National Botanical Garden. Once these trees had been identified, JCI had rectangular plastic labels made and quite a lot of information put on them and then attached them to the trees. Greenwood Park is quite a busy place not only for relaxation but also as a thoroughfare for many people. Unfortunately the majority of numbers and rectangular labels have been removed. Also disappointing to see was the burning of leaves right against two trees, one Ficus microphylla had a badly charred trunk and an Olea europaea. African olive had almost been killed.

Cordia myxa leaves and young fruit. Photo: Mark Hyde

Of interest was a Bauhinia tomentosa with many flowers and non-hairy pods. All the pods were hairless! Apparently this sometimes happens and sometimes there is no dark spot on the inside of the flower either.

Unlike the Quercus robur. English oak which doesn’t do very well around Harare – too warm, the Quercus palustris. Pin oak or swamp Spanish oak we encountered looked healthy. The fruit consists of flattened acorns.

However, the best sighting of the day was a tree new to us – Cordia myxa. Assyrian plum or sebesten. This tree couldn’t have had any leaves or fruit when we first labelled the other trees as it was in July 2017.

Tony Alegria

The following very interesting article is taken from Tree Life 150, August 1992. Rob Burrett contributed much to the interest of the outings of the Society, Ed

VEGETATION TYPES AND ARCHAEOLOGY IN ZIMBABWE

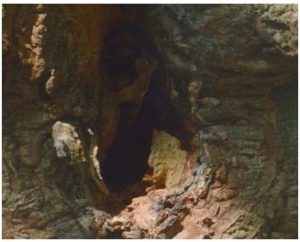

During recent visits to locate archaeological sites in the Matopos and northern Mashonaland I began to see a possible correlation between old occupation sites and certain floral types. This is just an‘ intuitive feeling at this stage, but one worthy of pursuit. Such a correlation could certainly prove a useful means of remote sensing, that is the discovery of new sites by both professionals and interested amateurs. The following are just a few ideas and I would appreciate any further observations and suggestions.

Why these correlations occur I think can be divided into two categories. There are those resulting from directly purposeful human activity such as the rooting of “cuttings” (poles in construction), or growing of seeds included in the deposit due to human activity (as food, medicine and spiritual use). In all these cases it is human activity which has directly led to the concentration of such plants on the site. On the other hand there are floral changes which are indirectly due to human activity. Here humans have influenced other elements which in turn have influenced the vegetation, eg changing soil conditions, run-off, incidental protection from fire and grazing, etc. It is this reasoning that needs the greatest attention right now.

The most obvious correlation is the dense concentration of thatching grass (Hyparrhenia spp.) on old sites, especially more recent Iron Age sites of the Refuge period. This is not my observation however, rather it was pointed out to me some time ago by Peggy Izzett. This is a good indication of occupation especially during the dry season when it stands out, often on hill-tops as distinct patches of yellow against the otherwise beige sea of grasses. So look out for this. I might add it is a useful indicator for locating sites on aerial photographs. As to why this relationship occurs, it seems that this is an example of inadvertent change. This grass occurs individually almost everywhere, but after human activity it becomes concentrated on such sites. It would seem that the occupants have unwittingly altered the local soil conditions, possibly through its compaction and the addition of ash thus altering the pH and chemistry of the soil. Only the Hyparrhenia seems able to tolerate this new regime and so it grows to the exclusion of all others. Another interesting plant is the Aloe, especially the larger shrubby or tree-like species, eg Aloe arborescens and Aloe cameronii (both common around the Nyanga Ruin sites and the well known Aloe excelsa such as in the Valley Complex at Great Zimbabwe. These plants although they do occur elsewhere are frequently associated with stone walling. Why they grow in these walls I have often asked myself. Certainly some of the smaller species are short term colonisers of degraded land but what of these larger types? I doubt they have grown from seeds or cuttings in the household debris. All too well one remembers the bitter aloe extract used to prevent pencil chewing at junior school, so I doubt they were eaten, but could they have been used as medicines or lotions? Suggestions much appreciated. One thing is certain, once established these plants thrive in the stone walls. Protected from grazing and fire damage they grow to enormous sizes, but in doing so it is true that they damage the walls by loosening the stones. Some of the wall problems at Great Zimbabwe are a direct result of the Aloe excelsa, hence their recent removal.

Aloe excelsea such as in the valley complex at Great Zimbabwe. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Down in the Zambezi Valley, especially on the old river terraces at Mana Pools and Chirundu, I have noted a correlation between Baobab (Adansonia digitata) and old Iron Age sites, which came first I cannot say; some of the trees are old and others comparatively young, but regardless of age of the tree it is rare to find a baobab without an adjacent site. Is it that the tree provided a focus for village life thus the village was built around it? Are such trees tied to the ancestors as is the case in Zambia where the swollen trunk is residence to the souls of the departed? The younger baobabs around the sites are also of interest. Were they planted with the ancestors in mind or have they just seeded from household debris?

In the Nyanga area there is a strong correlation between “pit structures” and at least one of each of the following: White Stinkwood (Celtis africana), Wild figs (Ficus species), Erythrina species, and Cabbage Trees (Cussonia species). These trees are relatively uncommon away from the pits and they form an excellent indication as they produce a dense evergreen canopy which can be picked out on aerial photographs and as you stand on neighbouring hills. Why the relationship?

Well the figs are obviously derived from the seed of consumed fruits, but the others are less obvious. The Celtis is an excellent hardwood and may have been used in construction, although I have found its truncheons don’t grow very easily. As for the soft wooded Erythrinas and Cussonias I cannot say. Any suggestions?

Various other trees are known to be good colonisers, taking root in newly disturbed conditions and growing there until matters revert to pristine conditions when they tend to die out. Unlike the softer tissue colonisers we call weeds, certain trees also grow and are useful indicators due to their long living period. Good examples of these being the various Euphorbia species. Tree Nettle (Urera tenax) and Acacia polyacantha . I doubt if any of these trees were directly planted or seeded from household debris, rather they are just part of the natural ecological succession after human disruption. The Euphorbias are of particular use because they stand out due to their large size and colouration. So keep a look out for them when looking for sites.

In the Matopos one frequently finds several trees associated with occupied shelters. That is not to say they don’t occur elsewhere but other wise their concentration is far less obvious. The trees being Milkwood, Mimusops zeyheri, various figs (Ficus species) and Grewia species. These plants I believe are probably derived from seed of consumed fruit, edible fruit being a distinctive feature of each.

An opposite case to the above is the Mahobohobo (Uapaca kirkiana). I have found that archaeological sites don’t occur in the vicinity of this species. The trees are obviously very intolerant of human interference. This is not to say they weren’t utilized for their excellent fruit, they just don’t seem to grow on sites unless it is particularly ancient. Thus don’t worry searching such places for you won’t miss much.

These are just a few of the relationships I have noted, there must be others. What I have tried to show here is that plants can be used to find new sites, they’re not all just randomly scattered. Human activity will lead to the concentration or dispersal of certain floral species, and it’s this we need to discover. However, matters should not stop there, for inferences on the social behaviour can also be made e.g. the economy, building techniques and even abstract religious beliefs. Should you know of further information on these or other species please let me know as I am working on it at present.

-Rob S. Burrett, Acknowledged with thanks Newsletter No. 85 of Prehistory Society of Zimbabwe.

ADDENDUM: After writing the above I came across a most interesting article in New Scientist of 25.1.92, entitled “Archaeology takes to the skies”, it discusses how variations in vegetative cover, as indicated in aerial photographs, can be used to discover archaeological sites. Work mostly seems to have been carried out in the America’s, but there are also references to classical Greece. Referring to it as phyto archaeology, the author, 0. Joyce, discusses how human activities have affected the moisture, chemical and temperature of soils. This in turn has led to changes in the types and densities of certain plants, as well as the chlorophyll content of these plants. He discusses how their technique has been used to trace lost roads of the Maya Civilization in the Central American forests, and how by noticing the spatial distribution of scrub oak (Kermes) in the limestone areas of Central Greece, lost Greek tombs have been relocated. So it is not just us amateurs that are looking at this subject of vegetation and archaeological sites. Any observations that we can make are not just academic, but will be of use to archaeologists in this Country.

-Rob Burrett .

ROOT NOTES :

And now my friends, a voice from the past, and what a pleasure it is to have another of Kim St. J. Damstra’s Root Notes. So many of us remember the Hay Days of the Tree Society when Kim and Phil and Cheryl and all the little Haxens added such spice on top of all the knowledge they shared with members. Let us welcome, with great pleasure, Kim’s contribution to this edition of Tree Life, and may it be the first of many. May it also inspire Phil and Cheryl to tell us a little of botanical, or other, happenings from “down under”.

Thank you Kim, may the dopamine continue to be released to help keep the life in the old lean and hungry dog to renew the tricks of contributing to Tree Life and so brighten our months.

Mary Lovemore, Editor

Note for Tree Life.

Kim Damstra

In my salad days in Zimbabwe when I was green in judgment, my friends felt I suffered from sublimation. In my defense Sigmund Freud believed sublimation was a sign of maturity and civilization. The threat (such are the friends one finds in the Tree Society) was to feed me on an infusion of root bark from Cassia petersiana (now called Senna petersiana).

This is not because the textbook (Coates Palgrave) states it is used to treat the spirochetes which they felt I had not given myself sufficient opportunities to catch, but rather because a few lines down it states “The root bark is given in soup or in milk … to make a lazy hunting dog lean and hungry and so more eager for the chase.” The term “lean and hungry” is so fixed in our language it was only this week while reading Shakespeare that I understood its origin in Julius Caesar’s speech on fat men:

“Let me have men about me that are fat;

Sleek-headed men, and such as sleep o’ night

Yon Cassius has a lean and hungry look;

He thinks too much: such men are dangerous.”

The “lean and hungry” quote from Shakespeare sounds like one of Keith’s jokes playing on the link between Cassius and Cassia, what a pity Linnaeus’s definition of Cassia sensu lato has been abandoned. Such is the state of my sublimated brain that links like this release a powerful fix of dopamine. It has been a while since my last submission to Tree Life, maybe it is time to sublimate once again: it may keep this old dog lean and hungry and ready for a new trick.

Kim Damstra

TONY ALEGRIA CHAIRMAN