TREE LIFE

October 2002

AS BEFORE PLEASE CONFIRM WITH ANY OF THE COMMITTEE MEMBERS THAT THE SCHEDULED OUTINGS AND WALKS WILL ACTUALLY TAKE PLACE. SEE THE BACK PAGE FOR PHONE NUMBERS.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday 8th October: Botanic Garden Walk one week later because of the Honde Valley trip. Meet Tom in the car park at 4.45 p.m. for 5 p.m. For the continuation of the family Leguminosae.

Sunday 20th October: To Mutoroshanga. Mrs Barbera Scheitler of Maringambizi Nature Area is our hostess.

We will meet at 9.30 a.m. Total distance from Harare is 105 km. Bring your lunch and a chair for an all-day outing.

Saturday 26th October: Mark’s walk is at. Lake Harava (Henry Hallam Dam), which used to be one of the Tree Society’s popular venues. It will be interesting to see how it has fared over the years. As usual we meet at 2.30 p.m.

Tuesday 5th November: Botanic Garden Walk.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Nothing has been arranged for October.

Shirley Dodds

It is with sadness that we report the death of Shirley on 5th August.

Shirley will be remembered by many; having taught at Goromonzi, Evelyn, Kwekwe and Roosevelt High Schools. She was a member of so many natural history societies besides the Tree Society, actively participating in the Wildlife Society, the Ornithological Society, the Mountain Club as well as the Harare Garden Club. Her knowledge was extensive and she shared it willingly with any interested party. Her scientific approach made her a great asset on the school camps at Rifa in Chirundu.

Another of Shirley’s talents was poetry and this is one of them.

‘Gold is the grass in the light of the morning,

Great granite boulders lie warm in the sun;

Tints of the trees when the leaves are unfolding

Splendid the skies when daylight is done.’

Most of us will remember Shirley with her cloth hat pulled well over her head, ambling along with her inevitable plastic shopping bag into which specimens were placed for later identification.

We admired Shirley for her guts and sense of humour and will miss her on our walks and outings.

CRAZY SEASON III

Today is the 27th of August 2002, and the msasa tree (Brachystegia spiciformis) that was reported to be flowering in mid-May (see TREE LIFE No 268) was re-visited to check on its present status. No new leaves and no flowers. So this tree, and many others that flushed and flowered unseasonally this year, may have to go through to August 2003 before they do so again. I saw no new pods from the May flowering, but perhaps a more critical examination might have revealed some. My experience of unseasonal flowering in eucalypts and pines is that nothing comes from it, and it would seem that this could be a general rule.

-Lyn Mullin

SANGANAYI CREEK, 21st July 2002

It is some years since we first visited Sanganayi Creek on Mazvikadei Dam, and it was great to find that the Scripture Union is continuing its policy of fostering an interest in the environment. Some trees were labelled and most in the campsite area were flourishing. We hardly needed to go far to find interesting contrasts, and a few specials.

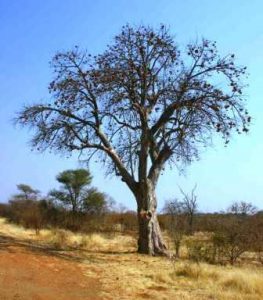

Acacia gerrardii. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

First to catch our attention were Acacia gerrardii, straight thorned, full of grey, almost velvety, dehisced earring-like pods with dangling seed charms, its leaves clustered on small knobs; and Acacia goetzei with small hooked prickles – which can cause horrid lacerations on unwary arms and legs – the leaflets, larger and less numerous, so probably Acacia goetzei goetzei. We then found Combretum collinum and Combretum zeyheri almost entwined, but the large 4-winged pale fruit of the latter were an obvious clue, whilst fruit of Combretum collinum were smaller and a dark pinkish brown. They may have a satiny bloom when fresh, and the narrower leaves did have a blue-grey tint. Later, we saw Combretum adenogonium still holding green leaves in whorls of three – usually by July they would be changing to orange or maroon before falling. The seed of this tree set and dry quickly after flowering, ready for the first heavy rains, whereas Combretum molle seed take months for the wings to dry and even old year’s seed may grow. We did not see game browse marks on the trees, or butterflies – Combretum molle is a noted butterfly host tree – but our bee-man reminded us that bees utilise Combretum and the honey is often bitter or strongly flavoured.

Boscia salicifolia. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

On a low termite mound nearby we found Boscia salicifolia drooping its longish, leathery leaves, the habitat, the sharp tip and markedly white midrib underneath the leaves making it easier to identify. Ormocarpum kirkii, with leaves growing from stubby branchlets, was full of dried flower heads with tiny, still green, segmented pods inside. The flowers, which the bees find useful, can range from a dull grey-maroon in colour in this area, to almost blue – Kadoma.

Pterocarpus rotundifolius subsp. polyanthus var. martinii – what a mouthful, but necessary to know as this has leaves with 7 – 8 pairs of leaflets which may be less rounded, where the Pterocarpus rotundifolius rotundifolius that we know from the highveld areas has fewer, broader leaflets. Both are a joy in mid-summer with their brilliant yellow, fragrant blossoming. Commiphora mollis, leafless, showed a milky pink slash in its bark, whilst Commiphora mossambicensis had smoother grey outer bark and was wrinkled where the branches grow from the main trunk.

Then back to feathery leaves, this time Acacia nilotica and Dichrostachys cinerea. Acacia nilotica was laden with popper-bead seed pods – scented yes, but apple-scented? Strange apples! – but undoubtedly a favourite game and stock browse. Dichrostachys cinerea, a valuable fodder tree – more for its contorted jumbles of seed pods – was another tree with leaves growing in clusters, but the branchlets ending in a single hard spine, a puncture maker par excellence. As we could see from the road entering the camp, this is one of the thicket-forming invader trees, (indicative of overgrazing in the past) and not popular with farmers. Perhaps in the Zimbabwe that is coming we shall say “any tree is better than no trees!”

Also on the termite mound and all around the area, Bauhinia petersiana with a few butterfly-winged leaves and curled and crooked branches that offer safe havens for bower-seeking birds, the large beans a famine stand-by for animals and man, and in summer a joyful starring of the bush with its delicate white flowers.

Across the road, Brachystegia boehmii, still in last season’s dress, balanced Brachystegia spiciformis a few metres away in new spring foliage, a bit early this year due to the rather warm winter perhaps? If the flowering is also early that will benefit the bees. Diplorhynchus condylocarpon, another species that copes with harsh conditions, drooped graceful branches, its leaves not yet gold, due to the lawn watering all round it. Next to the path Rhus tenuinervis was also fresh and green its softly hairy leaves, lightly scalloped and slightly bubbled from its tight margins – this had a few shiny brown seed, darker that those of Rhus leptodictya, which we were to see after lunch – both 3 foliolate, but the latter with longer, narrower, hairless leaves.

Further up on a large termite mound we found a Grewia that had smaller leaves, white-felted underneath but blue green velvety on top, smoother to the touch than we usually find in Grewia monticola, so a query; could it be Grewia bicolor? A large Ziziphus mucronata, baring its Wag’n bietjie thorns, lead us up to the top, and there the chopped side-stump of Cordia sinensis had some accessible new shoots with hairy, shallowly toothed leaves, in a fresh shade of green showing no hint of the grey in its common name. It was good to see it still existed where we had seen it on the first visit – not listed in Meg C-P’s key to the Trees of Zimbabwe, so is it fairly rare, or rarely a tree? Anyway, a special for us. At the bottom of the termite mound Ehretia amoena var. caerulea, with old harsh leaves; in October its pretty star flowers will be followed quickly by berries which birds will gobble up as soon as they turn orange. And then Balanites aegyptiaca, which we are more accustomed to seeing in Mopani woodland, held enough of its paired leaflets, and greeny-yellow spines to demonstrate the name Simple-spined Torchwood, but not the answer to the request for an elephant-proof hedging, as the seeds can be found in elephant dung!

All around the camp, typical clusters of Diospyros kirkii, many in fruit, proved the popularity of this food supply for birds, monkeys, etc., but unless fully ripe, not pleasant to eat. On a smaller termite mound Ximenia americana entangled with Dalbergia melanoxylon, another spiny puncture maker, and Grewia flavescens, the square-stemmed, shrubby Donkey Berry, offered birds food and nesting sanctuary, whilst a Rain Tree provided an attractive bench. Recently re-named Philenoptera violacea, this still had foliage at eye level so that we could note the swollen pulvinus and bend below the terminal leaflet that is its hallmark. When it blooms in November, a lavender mist from a distance, the tiny flowers are indeed a lovely blue-violet, and are heavily visited by bees. As is Vernonia colorata, which is especially valuable for its winter-flowering regime.

Then on another termite mound at the receding water’s edge, in a thicket of Flueggea virosa and Capparis tomentosa (more food for birds in season, especially Louries), a great favourite of mine from Chegutu, large Lannea schweinfurthii var. stuhlmannii, where, except for the leaves (usually a pair of leaflets and a larger, rounded terminal one, lightly hairy and a yellow-green), the tree could be mistaken for a Marula. And on our way to lunch the other Lannea, Lannea discolor, leafless but the thickened wrinkled growing tips and rubbery bark were unmistakable. Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia with scattered autumnal leaves, and a number of Gardenia ternifolia caught our eyes. The fruit of both are eaten by animals, whereas the sharp-tipped, dried flower fruit of Monotes glaber seem to lie around for insect attacks. Our first and only fig of the day, a small Ficus thonningii, was just starting its life in the ‘‘shoe’’ of a Monotes, and not far away the dwarf Ochna macrocalyx had somehow survived mowing, horses and feet – so pretty when in flower or fruit.

Chionanthus battiscombei. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

And so to lunch, passing trees planted by the management of the camp: – a Podocarpus, Mimusops zeyheri, Rhamnus prinoides, Chionanthus battiscombei, Celtis africana, Olea europaea africana and an exotic Pachira nut, all of which will need watering. Lunch on the lawn had hungry horses hovering in hope of handouts – yeah, this is Zimbabwe! And the doom and gloom was somewhat dispelled by the stream of nonsense which we can always expect from Miles – thank you for that, friend! Afterwards, a few of us went uphill to the burned area, passing Albizia amara, Peltophorum africanum and Securidaca longipedunculata, all laden with seed, awaiting the rains; until finally a last special, Zanthoxylum chalybeum, shooting at ground level from a chopped out stump, its shiny compound leaves with serrated leaflets and prickled petiole giving off the diagnostic lemony scent when crushed.

All in all, a pretty good selection of trees when one remembers the really difficult shallow soils of the area, and its lower rainfall, proving the value of trees in such countryside. Let us hope that Sanganayi Creek will continue to act as a seed reservoir when all around trees are cut out and horrendous fires compound the damage. Since I first started these notes more and more farms have been given Section 8 notices, and more and more fires are being lit, more trees cut out, and it is not easy to keep a smile at hand – but we have many good memories of Tree Society outings in such wonderful company, and this no-one can take away. A warmly felt thank you to all who have shared in this love not only of trees, but of the environment!

A.B

BINOCULAR BOTANY (the fun and the frustration of it)

A very recent long weekend (31 August to 3 September) at Kariba, aboard the small houseboat Stormvogel, took me back to territory that I had worked and camped in during two 6-month tours of duty for the Forestry Commission in 1956 and 1957. We were tied up for most of the weekend in various parts of the Gache Gache inlet, where the fishing was fairly good. But as I no longer have the tolerance of the sun that is so essential for fishing from an open boat, my own time was largely spent under the upper-deck canopy of the houseboat, armed with a pair of 1957-vintage, 8 x 30, German-made, Sperber binoculars. I also had access to a pair of 2002-vintage, 10 x 50, Japanese-made glasses.

The game viewing was pretty good, and we saw most of what was on offer on land and in the water, including many, hideously large crocs. The bird life was magnificent, and gave us endless pleasure, including the interesting spectacle of a fish-eagle taking a long and leisurely bath – it must have been at it for all of 20 minutes, and then hung out its wings to dry in the way a cormorant does. At least two fish-eagles indulged in “trophy hunting”; they caught and killed large fish, but consumed only the heads, leaving the bodies to rot in the sun.

The trees and woody shrubs fell into four categories – those just coming into new leaf; those that had not yet completely shed their leaves; those that were completely leafless; and those that are normally evergreen – and trying to identify them through binoculars made for a lot of problems. I longed to get off the boat and wander around the more interesting patches, but the boat crew warned us that this was strictly forbidden; the whole shoreline is controlled by National Parks, and the boat crew would find themselves in trouble if they allowed passengers to disembark ad lib. So, there was no other course but binocular botany.

Terminalia prunioides. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Basically the area was mopane country, but among the more conspicuous species was Terminalia prunioides (Purple-pod Terminalia) with its purple-red fruits. Some specimens were in flower, which, according to the books, is a bit unseasonal. There was another largish tree, some distance from the boat, with unmistakable Terminalia fruits, but not identifiable beyond that since it lacked the typical, layered branch habit one associates with the genus. Albizia anthelmintica (Worm-cure Albizia) was common-leafless, but identifiable by its flowers. Triplochiton zambesiacus, also common, still had plenty of its lobed leaves to make identification easy, and tall Kirkia acuminata (White Syringa), with last year’s capsules conspicuous on the uppermost branchlets, could be picked out here and there. One very tall specimen of Entandrophragma caudatum (Wooden-banana tree), standing some 200 metres away, was easily identified without the aid of binoculars, as it was covered in its typical capsules, which look for all the world like peeled bananas. One of the crew members said that the Korekore people call it mukonde, but I am hesitant about that, for mukonde is the name, in all Central Shona dialects, for Euphorbia ingens. Can any readers of TREE LIFE in the Kariba area confirm that mukonde is a valid Korekore name for Entandrophragma caudatum? No checklist published so far has any Shona name for the species.

There is a striking difference in the dominant vegetation between the two sides of the Gache Gache inlet. The north-eastern bank is dominated by baobabs and what I took to be Euphorbia fortissima (the main stem was short and the branches appeared through the binoculars to be mainly 3-winged, but I could not be certain about that). The opposite bank had hardly any baobabs or euphorbias. Was this difference due to aspect or to a change of soil?

Acacia karroo was common and easily identifiable, Acacia tortilis less common, and a little more difficult to identify except when there were a few pods remaining on the trees. Trying to pick out straight and hooked thorns through the binoculars was impossible. There was also one specimen of what appeared to be Acacia ataxacantha (Flame-pod), but too far away for a good look. Acacia nigrescens (Knob thorn) was nearly, but not quite, absent, a feature I have noted frequently in mopane country; although the two species occur in the same area, they don’t seem to occupy the same sites. The few Knob thorn specimens that were present were all in flower. Faidherbia albida (Apple-ring acacia, or simply albida) was present in modest numbers near the water’s edge, and was easily identifiable by its grey-green foliage.

Sterculia africana. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Both Sterculia africana (Tick tree) and Sterculia quinqueloba (Large-leaved Sterculia) were present in the area, but more of the former than of the latter. Neither had any leaves, and identification had to rest on differences of form and habit. There was also the odd leafless Combretum imberbe (Leadwood), not difficult to identify because no other species looks quite like it. There was also one specimen of a Bauhinia with some leaves and fruit; I could not get a good look at the leaves, so it could have been either Bauhinia petersiana (White Bauhinia) or Bauhinia tomentosa (Yellow Bauhinia).

Leafless unidentifiables were common, including one or more species of Commiphora, and leafy unidentifiables were also plentiful, their glaucous foliage suggesting members of the family Capparaceae. There was also a specimen of what appeared to me to be Ipomoea shirambensis (Zambezi morning-glory) in full flower, and guess what? One specimen of the ubiquitous Ricinus communis (Castor-oil plant) to let you know that you can’t get away from it!

One of the most interesting things to me was to see a live and healthy specimen of Kigelia africana (Sausage tree) on a spit of land subject to inundation when the lake is full. Every other tree on this site was long dead, so how did the Sausage tree get away with it?

On the open water there was very little Kariba weed (Salvinia molesta), but in the sheltered inlets it was quite matted. In between these two extremes there were plenty of small clumps of the weed, each seemingly with its own resident dragonfly doing whatever dragonflies do on Kariba weed. I began to get the impression that each clump of weed was a complete ecosystem-supporting other plants and insects, with a whole colour-range of dragonflies distributed between the clumps.

-Lyn Mullin

THE ANNATTO TREE

The Annatto tree, Bixa orellana, (Family Bixaceae) may be a large shrub, or a small tree 2-5 m tall. It is native to tropical America, but is grown in many countries for the vegetable pigment, annatto, that is used for colouring dairy products, bakery products, edible oils, and other foodstuffs. Annatto is incorporated in pottery in Brazil, and has a wide range of other uses, such as an insect repellent applied directly to the skin, and as an ingredient in floor-wax, furniture and shoe polishes, nail gloss, brass lacquer, hair oil, and wood stains. The pigment was formerly used in cosmetic, leather, and textile dyeing.

The plant is very variable, from trees with green stems, white flowers, and green fruits to those with red stems, pink flowers, and dark red fruits. The fruit is a burr-like capsule or pod covered with fleshy spines, varying in size and appearance from round to elongated with pointed ends. The fruit is usually divided into two valves containing 10-50 small seeds coated with a thin, pulpy, resinous layer of bright orange to yellow or red arils from which the commercial dye is obtained.

The main commercial producers of annatto are located mainly in South America and the Caribbean region, and the crop is produced on a smaller scale in Africa, in Angola, Kenya, and Tanzania. The species grows best in the hot, humid tropics, but healthy specimens are seen in gardens in Harare and elsewhere in Zimbabwe (for example, we saw a specimen on Mark’s walk at Ewanrigg on 27 July).

The main constituent of the colouring matter surrounding each seed is bixin, an oil-soluble carotenoid that is a monomethyl ester of a dicarboxylic acid. The alkali hydroxide salts are water soluble, and the potassium salt is used as a dye in foods such as cheese. Two processes are used in the extraction of the commercial product. In the first the seeds are steeped in hot water for some hours to produce crude pigment, which is then dried, milled, and powdered. The second process involves direct extraction with a vegetable oil or other suitable solvent. Whatever method of production is used, care has to be taken to avoid unnecessary or prolonged exposure to heat, acid, alkali, and light all of which cause the degradation of bixin.

(Condensed from: J.S. Ingram and B.J. Francis (1969), The Annatto Tree (Bixa orellana L.), Tropical Science Vol XI, No. 2.)

-Lyn Mullin

In Retrospect: Lyn Mullin. Continued

BIBLICAL ACACIAS

TREE LIFE No.127 (September 1990) carried the second of two articles by Kim Damstra, titled “Trees of the Bible”. By inference, not by direct assertion, Kim identified Acacia seyal and Acacia tortilis as the acacia trees referred to in the Bible, since they are both present in the Negev and Sinai areas. However, different viewpoints have been expressed, as we shall see below.

There are at least 31 references to acacia in the Old Testament, and no less than 27 of them are connected with the specifications for the Ark of the Covenant, the table of the offertory bread, the framework for the tabernacle, the supports for the veil, the altar of sacrifice, the altar of incense, the collection of materials for these works, the actual construction of these items (all in Exodus 25: 5-38: 6), and a summing up of what had been accomplished (Deuteronomy 10: 3). Throughout all these references the Authorized (King James) Version (AV) uses the term shittim wood, clearly borrowed from the Hebrew shittiym (modern Hebrew sittim), derived from shotet, to pierce or scourge, referring to the thorns of the acacia.

Some commentators believe the species in question to be Acacia seyal, described as “the scented acacia of Palestine which furnished the shittim wood so much esteemed by the ancient Jews” (E Cobham Brewer, 1906, Dictionary of Phrase and Fable). It was also said to be the only tree of any size in the Sinai Desert, where much of the Exodus story was enacted; it has been a minor source of gum arabic for untold years, its bark is astringent and has been used in tanning, and its wood is still widely used in the Sinai region (Werner Keller, 1956, The Bible as History).

The fragrance of Acacia seyal is alluded to in Ecclesiasticus (or Sirach) 24: 15, where the Jerusalem Bible has “I have exhaled a perfume like cinnamon and acacia”, and Isaiah refers to it symbolically in his vision of a restored and faithful Israel (Isaiah 41: 19, where AV has shittah tree, and most other versions have acacia).

More recent opinion on the identity of the acacia wood of Exodus and Deuteronomy is quite different from what had been expressed earlier (Nogah Hareuveni, 1984, Tree and Shrub in Our Biblical Heritage). The text of Exodus 25: 5 and 35: 24 indicates that the Israelites already had acacia wood in their possession, implying that it had been brought with them from Egypt, rather than collected from any species in Sinai. In addition, the length of the central bar of the Tabernacle (Exodus 35: 33) must have been about 15 metres, which is inconsistent with the growth habit of Acacia seyal or Acacia tortilis; but it is consistent with the growth habit of Faidherbia albida (Acacia albida), which is indigenous in the Nile Delta region, the traditional location of the period of Israelite enslavement in Egypt. Faidherbia albida does not grow in Sinai, and according to botanists it never has (Hareuveni, 1984).

The thickets of the Jordan (Jeremiah 4: 7, 12: 5, 49: 19, 50: 44) are home to two other acacias besides Faidherbia albida; these are Acacia tortilis and Acacia iraqensis, which have also been proposed as the acacias of the Bible (The New Bible Dictionary, 1982, and The Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 1994), but without any convincing arguments.

To sum up, Faidherbia albida can probably be identified as the acacia of Exodus and Deuteronomy, and Acacia seyal as the acacia of Ecclesiastiacus (Sirach), possible also of Isaiah 41: 19.

And a footnote for the purist – Acacia tortilis is represented in the Sinai Peninsula by two of its four subspecies, tortilis and raddiana.]

DYLAN THOMAS’S MILKWOOD

In the contribution from the Nyarupinda Catchment in TREE LIFE No. 128 (October 1990), I.M.B.G asked for suggestions on the identity of the trees in the Welsh village in Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood, which was written in 1954. No one seems to have replied, or, if they did, the replies did not find their way into TREE LIFE. Is the question still open? And are there any suggestions?

SACRED TREES

In TREE LIFE No. 132 (February 1991) the Nyarupinda Catchment series made reference to Kirkia acuminata (White Syringa) as a sacred tree.

Kirkia acuminata has not received much attention in these pages, so here goes. The tree is sacred to some African tribes. Thanks to Stephen Mavi for those notes that were made many decades ago. Mubvumira and umvumila are Shona words meaning `to agree with’, and refer to a legend about this tree. The spirit of Chaminuka looked for a place to dwell and, eventually, probably a particular specimen of Kirkia allowed the spirit to enter it. The name umvumila (variously spelt) was applied to all specimens of this tree, which then became holy among the Mashona people.

[Comment 2000: Mubvumira is the Shona name for Kirkia acuminata, but umvumila is the Ndebele name – there is no “um” prefix in Shona, and no “mu” prefix in siNdebele. The closeness of the two names suggests that the Ndebele people became aware of the sacredness of the species, and adopted the Shona name – but pronounced it their own way. The Shangaan name for the species is vumaila – also close to the others.In his A Political History of Munhumutapa c.1400-1902, by Dr. S.I.G. Mudenge, published in 1988, the author mentions the Mitimichena shrine in the foothills of the Mavuradonha Range. This shrine was an important site in the Mutapa period – and possibly it still is – but it is not clear whether its location is within the present-day borders of Zimbabwe, or of Mozambique. The author records that the Mutapas often contacted the officiating priest at the Mitimichena shrine, and quoted old Portuguese documents as evidence of this. It is quite clear from the Portuguese writings that the Mutapas stood in awe of the officiating priest, and did not dare to ride roughshod over him.

Mitimichena means white trees, and the author identified these as mituwa, the Korekore name for Kirkia acuminata. From this distance in time it is interesting to speculate: did the shrine confer its sacredness on the tree species, or did the shrine receive its sacredness from a tree species that was already held as sacred? Any ideas from the Tree Society?

SWYNNERTON’S JACARANDAS

The familiar jacaranda, Jacaranda mimosifolia, a native of Brazil and Argentina, is probably Zimbabwe’s favourite ornamental and street tree, and the straw-coloured wood can be used very satisfactorily for carving and even for cabinet making. The tree has become naturalized in Zimbabwe, and it was even tried for plantation use by the great naturalist C.F.M. Swynnerton (1877-1938), who established a stand on one-third of a hectare on the edge of Chirinda Forest in about 1913. Jacaranda has a spreading crown, and is therefore not a good plantation species, but Swynnerton’s stand has, nevertheless, grown surprisingly well.

It was measured in 1963 when the mean height was found to be 21.3 metres and the mean diameter 35.0 cm. Practically all the trees had several stems arising from ground level, and the total number of stems in the measured sample was the equivalent of 1 186-ha – severe overcrowding for a tree of this kind. By 1975, the number of stems per ha had decreased slightly to 1 088, the mean height had increased to 24.1 metres, and the mean diameter to 39.7 cm. The species continued to show a surprising capacity for tolerating crowding and for making use of the site, but the short average bole length of only 6.1 metres kept the total volume of stem wood down to a very modest 410 cubic metres-ha. In July 1987, individual stems had breast-height diameters up to 70 cm, with whole-tree diameters at ground level up to 1.3 metres. Heights were difficult to measure accurately, but the tallest trees were up to 30 metres or more. For comparison the largest jacaranda known in Harare, at No. 32 Ridge Road in Avondale, had a stem diameter (at 80 cm above ground level) of 1.4 metres, a height of 24.5 metres, and a crown spread of 38.5 metres when it was measured in October 1987.

There is often justifiable concern about the uncontrolled spread of jacarandas in certain parts of the country, e.g. around Marondera, but there is no evidence of them spreading naturally into Chirinda Forest from Swynnerton’s plantings.

THE LUPANE UMTSHIBI

Guibourtia coleosperma. Photo: Vivien Williams. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Not many large Umtshibi trees managed to escape the woodcutter’s axe during the heyday of timber exploitation in the dry, deciduous forests of Zimbabwe’s Kalahari sands, so we don’t know today just how big these trees could become. Umtshibi, Guibourtia coleosperma, is one of the three major commercial components of the Kalahari-sand forests of north-western Matabeleland, and along with Zambezi teak, Baikiaea plurijuga, has supplied most of the wooden railway sleepers and parquet flooring produced in Zimbabwe over more than 80 years.

The largest Umtshibi known in Zimbabwe today stands at kilometre 70 on the road from Bulawayo to Victoria Falls. The second largest, and a finer-looking tree than the first, stands exactly halfway along the 5-kilometre stretch of tarred road linking Lupane administrative centre with the main highway to Victoria Falls. It is on the south side of the link road, and just off the tar. In June 1987 it was 22 metres tall, with a diameter at breast height of 1.19 metres, a crown spread of 21 metres, and an unbranched bole length of about 4 metres. The wood of this species is of the same weight and colour as that of Zambezi teak, but it lacks the black flecks and streaks that are characteristic of the latter. Umtshibi seeds can be roasted and ground into an edible meal, and the oily red arils have been a famine food in times past.

-Lyn Mullin

MARK HYDE, CHAIRMAN