TREE LIFE

FEBRUARY and MARCH 2002

AS BEFORE PLEASE CONFIRM WITH ANY OF THE COMMITTEE MEMBERS THAT THE SCHEDULED OUTINGS AND WALKS WILL ACTUALLY TAKE PLACE. SEE THE BACK PAGE FOR PHONE NUMBERS.

THE ANNUAL SUBS ARE DUE ON 1ST APRIL AND UNFORTUNATLY WITH ALL OUR COSTS SPIRALING UPWARDS SO RAPIDLY AN INCREASE TO $400 IS UNAVOIDABLE

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday 12 February. Botanic Garden Walk. Please note the change of date owing to the Nyanga trip.

Meet in the car park of the Botanic Garden at 4.45 for 5 p.m. where we will meet Tom and continue with the Rubiaceae family.

Sunday 17th February. Cleveland Dam is the venue for this month’s outing. Lyn Mullin has found a delightful area in which to walk and a lovely spot for our picnic lunch which is quite secluded.

Saturday 23rd February. Mark’s walk is a return visit to a well treed area in the Ruwa area, the home of Rick and Sally Passaportis, which was a very popular venue for the outing in June last year. Meet at the house at 2.30 p.m.

Tuesday 5th March. Botanic Garden walk.

Sunday 17th March. Perhaps in the Banket area.

Saturday 23rd March. Mark’s walk.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

There will be a trip organised by the Matobo Conservation Society to Tshangula cave in the southern Matopos on Sunday 17 February 2002. We will all meet at 9.00 at the Churchill Arms car park, where lifts can be arranged if required. All members of the Tree Society are invited. Please bring your own chairs, food and drinks. Check with Jonathan Timberlake closer to the time about road conditions, but it should be accessible by normal vehicles.

No other arrangements have been made for February. Contact Jonathan Timberlake if you would like to organize a future outing.

TREE FLOWERING By Peter Taylor

The sparse flowering of jacaranda has been commented upon recently in Tree Life, and Tree Life 262, December 2001, gives a Bulawayo record of Acacia galpinii and A. karroo not flowering at all.

In and around my apiary site in Banket, I have several Albizia versicolor which flowered prolifically in 2000 and set a mass of fruit, no doubt due to pollination from my bees. But this year they haven’t flowered at all. Is it possible that a heavy seed set inhibits floral initiation, the seed set perhaps being due, in part, to optimum moisture levels caused by several good rainy seasons in a row?

Suggestions and comments please!

NEW CONIFER FOUND IN VIETNAM

The following appeared on the BBC’s web site on November 25th, 2001.

An international team of scientists has found a new conifer in the forests of northern Vietnam. The tree, a new species in a new genus, has been named the Golden Vietnamese cypress.

Its discoverers say it is a missing link between true and false cypresses. But although it is new to science, the tree is already critically endangered, and only a few individuals exist.

The team that discovered the tree included scientists from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK; the Vietnamese Institute of Terrestrial Ecology in Hanoi; the Komarov Botanical Institute in St Petersburg, Russia; and the Missouri Botanical Garden, US. They were in the area to study the orchids of the karst mountains of northern Vietnam.

The new cypress is a small tree with unusual foliage – the mature trees carry both needle leaves and a scale-like form, which are usually found only in juvenile individuals. The scientists made their discovery in October 1999, but waited till now to confirm it.

Kew’s conifer specialist, Aljos Farjon, told BBC News Online: “I was shown some slides of what they’d found, and I have to admit that at first I dismissed the possibility that it could be anything new. Then I saw a specimen. But I decided I needed to see another before I could make up my mind”.

The team went back to the area in February 2001 and brought back another specimen.

“I was excited to realize what it was, both for the sake of the new species and because it starts answering a few funny questions. The nearest relative of the new tree is the Nootka cypress of North America, itself a parent of Leyland’s cypress, known to gardeners and loathed by many of them. Now we may be able to find out why the Leyland, although a hybrid, is sterile.

Because we now know the Nootka cypress is not exactly what we’d thought, we’re having to give both it and the Leyland new scientific names. The Leyland’s new name is a bit shorter. Perhaps that will mean it stops growing so fast.”

The Golden Vietnamese cypress, Xanthocyparis vietnamensis, is the first new conifer found since the Wollemi pine’s discovery in Australia seven years ago. Before that, there had been no new conifers described since 1948. But Xanthocyparis is in trouble. It is naturally rare, found only on limestone ridges in a small area close to the Chinese border.

And the local people like to use its fragrant wood for building shrines and making coffins. Only a few semi-mature and coppiced trees exist. The golden cypress is the latest in a line of newly-discovered species in south-east Asia.

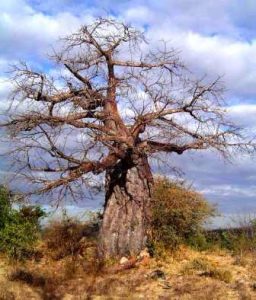

This month is the start of a fascinating story about our Baobabs compiled by Lyn Mullin. It will be spread over several months. The first part deals with the scientific information and some folklore and subsequent parts with folklore and other interesting stories and facts.

BAOBABS IN MY SOUP

Introduction

Adansonia digitata. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Very recently I received on loan a small book titled The Baobab in Fact & Fable, written by Rowan Cashel, a retired District Commissioner who died in July 1995. The book was produced and printed privately, and runs to 192 A5 pages, of which 32 are taken up by illustrations. I had had some correspondence with Rowan Cashel while he was preparing the book, and he was going to show me a copy, but he died before I could meet him. It was only the chance visit to an elderly friend in South Africa, the widow of another retired District Commissioner, that finally put the book into my hands.

There is much in Rowan Cashel’s book that might be of interest to readers of TREE LIFE, and summarized extracts from it, together with material from my own files and from other sources, will be combined into a single article on baobabs generally, but more particularly on our familiar African baobab.

It was noted Arab traveller, Ibn Batuta (1304-1369), who first brought outside attention to the African baobab. In his Rihlah, the account of his travels, he commented on a weaver in Mali whom he had seen weaving his cloth in the shelter of a hollow baobab.

The name baobab was probably derived from bu hobab or bu hibab – ‘the fruit with many seeds’ – the name the fruit was sold under in Cairo markets in the late 16th century.

Systematics

The genus Adansonia comprises eight species, six endemic to Madagascar, one to north-western Australia, and one originally from continental Africa that has been dispersed widely by man within the tropics, including Madagascar where it has become naturalized.

Adansonia was named for French botanist Michel Adanson (1727-1806), who first came across baobabs in Senegal, West Africa. The genus is divided into three sections:

Section Brevitubae (2 Madagascan species) with erect, ovoid flower buds, and short, staminal tubes. A. grandidieri and A. suarezensis.

Section Adansonia (1 African species), with pendent, globose, flower buds, and long staminal tubes. A. digitata.

Section Longitubae (1 Australian and 4 Madagascan species), with erect, very elongated flower buds, and long staminal tubes. A. gregorii (Australia), A. rubrostipa, A. madagascariensis, A. za, A. perrieri.

There is some evidence to suggest that West African populations of A. digitata may be taxonomically separable from those of eastern and southern Africa.

Two of the Madagascan species have been divided into varieties. These are – A. rubrostipa (var. rubrostipa and var. fony), and A. za (var. za, var. boinensis, and var. bozy).

Flower Colours and Flowering Period

Adansonia digitata. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Adansonia digitata (white, Adansonia grandidieri (white), Adansonia suarezensis (white), Adansonia gregorii (white), Adansonia rubrostipa (yellow), Adansonia madagascariensis (yellow or red), Adansonia za (yellow), Adansonia perrieri (pale yellow).

The flowering period of the two species in Brevitubae, Adansonia grandidieri and Adansonia suarezensis is in the dry winter months (May-September), and all the others flower in the wet summer months (November-March); Adansonia digitata at the start of the wet season (which varies across its range); Adansonia za, Adansonia perrieri, and Adansonia gregorii in the early part of the wet season (November-January); Adansonia rubrostipa in the middle of the wet season (February-March); and Adansonia madagascariensis flowers at the end of the wet season (March-April). The flowers open around dusk, and produce nectar for the one night only, although they may remain on the tree for 1-4 days.

Pollinators

There are two main pollinating systems in Adansonia, one carried out by nocturnal mammals, and the other by long-tongued hawkmoths, and these two systems are correlated closely with differences in floral morphology, phenology, and nectar production.

Proven pollinators of Adansonia digitata are three fruit bats, Eidolon helvum (Straw-coloured Fruit Bat), Epomophorus gambianus (Gambian Epauletted Fruit Bat), and Rousettus aegyptiacus (Egyptian Fruit Bat). Zimbabwe is in the migratory (but not main) range of the first of these bats; the Victoria Falls region as far as the upper limit of Lake Kariba lies within the main range of the second species; and the range of the third species covers all of Zimbabwe except the extreme west. The distribution of the three fruit bats coincides precisely with the distribution of Adansonia digitata. In Madagascar there are also three fruit bats, Eidolon dupraenum, Pteropus rufus, and Rousettus madagascariensis. Fruit bats are believed to seek the nectar that is secreted by a ring of calyx tissue around the base of the ovary in all species; in sections Brevitubae and Adansonia the nectar is easily accessible, but there is restricted access to it in section Longitubae.

In Africa the Thick-tailed Bushbaby, Otolemur crassicaudatus, is also thought to be a pollinating agent since it feeds on the flowers of Adansonia digitata, but some observers believe that this bushbaby is too destructive of the flowers to be an effective pollinator. In any case, the bushbaby’s distribution in Africa covers only a very small part of the baobab’s range.

Observations in Madagascar indicate that the two species of Brevitubae are primarily pollinated by nocturnal mammals, Adansonia suarezensis by fruit bats, and Adansonia grandidieri by the Forked-marked Lemur, Phaner furcifer, but bat pollination of this latter baobab could not be ruled out. Four of the five species of Longitubae, Adansonia rubrostipa, Adansonia za, Adansonia perrieri, and the Australian Adansonia gregorii are pollinated by long-tongued hawkmoths of the family Sphingidae. The fifth species of section Longitubae, Adansonia madagascariensis, has not been sufficiently studied to provide reliable information on pollinating agents, but there is some evidence of minor pollination by honeybees.

Suggestions that sunbirds and ants also play a part in baobab pollination have not been supported by any positive evidence, although they are known to be regular visitors to the flowers in search of nectar. Other visitors to baobab flowers are bluebottles, at least three species of bollworm moths, flies, butterflies, and settling moths, but none of these is a known pollinator.

Normal Habitat

The African baobab is a component of the drier regions of Africa, with rainfall ranging from 200 mm to 800 mm annually, but there is no doubt that its currently mapped range in Africa includes areas that have been extended by man. Its importance as a source of food, water, and raw material for various products would have ensured its dispersal by man and animals throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa.

In Zimbabwe the baobab is an inseparable part of the Zambezi Valley and the Save-Limpopo lowveld at altitudes up to 600 m, but it does also occur in other, less likely, areas, e.g. the single specimen just outside Kadoma on the road to Gweru, the occasional specimens in the Kalahari-sand regions of north-western Matabeleland, and the population in the Nyanga North region growing naturally at an altitude of more than 1200 m. The highest altitude that has been recorded for a naturally growing baobab in Zimbabwe is 1330 m in the Nyanga North area; the observation was made in 1951, but the tree has long-since died and disintegrated.

Baobabs have been planted well outside their natural range both in Zimbabwe and elsewhere. The National Botanic Garden and Greenwood Park in Harare contain some thriving specimens, and there are two trees at No 14 Arcturus Road in Highlands at an altitude of 1520 m. Baobabs were successfully grown in England as long ago as 1720, reaching heights of more than 5 m before the severe frost of 1740 killed them all.

In Australia the baobab (or boab as it is called) is confined to open woodlands of the Kimberley region of the north of Western Australia and the northwest of Northern Territory. The latitudinal range is 14-18°S, and the altitudinal range is from near sea level to 400 m. The mean annual rainfall is 500-1500 mm, with a long dry-season.

Baobabs in Madagascar extend from the extreme north to the extreme south of the island, in the dry region west of the central mountain chain. They are usually canopy or emergent forest trees of the lowlands, but Adansonia perrieri grows in rainforest at altitudes of up to 650 m. At the other extreme, Adansonia madagascariensis, Adansonia suarezensis, and Adansonia rubrostipa can all be found in coastal scrub that may occasionally be inundated by sea water.

Adansonia perrieri and Adansonia suarezensis face extinction in the foreseeable future due to degradation of habitat by human activity.

Size Attained by the African Baobab

The African baobab is probably the largest of the eight species of Adansonia. It is certainly very much larger than the Australian species, which reaches heights of 12-25 metres and diameters of up to 6 m. No data have been seen for the Madagascan baobabs (except for Adansonia perrieri, which may exceed 25 m in height), but photographs suggest heights and diameters comparable with those of the Australian species. Reliable reports of African baobabs with diameters of 10.82 m and 10.64 m have come from Sudan and South Africa, respectively, but unconfirmed reports of diameters of 17.7 m and 17.35 m have appeared in the Guinness Book of Records. Attempts to verify these records have met with no response. In Zimbabwe the largest known diameter for any baobab is 8.79 m for a tree on Devuli Ranch in the Save Valley, and the tallest height is 27 m for another tree in the same area. The pre-storm-damage height of 47.5 m recorded by Rowan Cashel for the ‘Big Tree’ at Victoria Falls is clearly erroneous. This tree was said to have been truncated by a violent storm in 1960, but there is no way that a claimed height of over 47 m could be accurate. Such heights belong to rainforest trees, not to trees of dry-country woodland. In 1985 the ‘Big Tree’ at Victoria Falls had a diameter of 7.02 m, and the height of 24 m was very much in proportion to the diameter.

Age

Here we enter the realm of speculation, but it might not be wildly inaccurate to suggest an age of 3000 years for a really big African baobab. Carbon dating of a tree of 4.5 m in diameter from the Kariba Basin was carried out by Dr ER Swart at the (then) University of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and he came up with an age of 1010 years ±100. If this is used as a yardstick, a tree of twice that diameter could well be three times the age, because diameter growth cannot possibly be maintained at the same rate throughout the life of a tree – even if the same volume of wood is produced each year (see also the contribution by GL Guy in Rowan Cashel’s book).

The first attempt to calculate the age of a baobab was made by Michel Adanson when he examined two trees in Senegal in 1749, and concluded that they were 5150 years old. Some 100 years later this infuriated David Livingstone, who belonged to the school of thought that had calculated the Year of Creation as 4004 BC. Adanson’s calculations put these trees on earth before the Great Flood, and what annoyed Livingstone was the inference of no Flood! But when Livingstone himself set about dating a large old baobab, he arrived at a figure of over 4000 years!

The Tree of Plenty

Practically all parts of the African baobab are used by man. The roots provide a red dye, and can even be eaten; the bark fibre is used for making mats, baskets, clothing, and medicine; the leaves make a good substitute for spinach, and they can also be used medicinally; the pith surrounding the seeds may be mixed with water to make a refreshing drink, or it can be used as a substitute for cream of tartar; and the hard pods have many domestic uses.

The story is much the same for the Madagascan baobabs. Adansonia rubrostipa provides mushrooms from the fallen trunks; the hollow trunks of Adansonia grandidieri and Adansonia za are used as water cisterns; the bark of the latter two species is used for rope; the sap of Adansonia grandidieri is drunk fresh; the wood of Adansonia grandidieri and Adansonia rubrostipa is used for thatching huts, that of Adansonia grandidieri is burnt as fuel, and that of Adansonia grandidieri and Adansonia za is fed to cattle; seedling roots of Adansonia grandidieri, Adansonia madagascariensis, Adansonia rubrostipa, and Adansonia za are eaten; the fruit pulp of all species is eaten fresh, and is also thought to be used medicinally; and the seeds of Adansonia grandidieri eaten fresh, and an oil is extracted from them.

In Australia the boab is important to the Aboriginal people. The pulp is eaten dry, or mixed with water as a beverage; the trees are sources of water, just as they are in Africa and Madagascar; the bark is rolled to form twine; a gum was traditionally made from the pollen, and was said to be used for fixing heads to spears; and the fruits are carved as ornaments. An early observation from Australia was that the Aborigines used to carve marks on boab stems, apparently to record the number of fruit taken.

Hollow trees in Africa have provided water-storage reservoirs from time immemorial, and a large tree can hold up to 900 litres. No wonder, then, that old slaving and trading routes followed a path from one hollow baobab to another across vast arid tracts. In more modern times hollow baobabs have been put to a great variety of innovative uses – bus shelters, cold rooms, dairies, dwellings, flush toilets, jails, storerooms, tombs, and probably many more.

DR LIVINGSTONE’S MONOGRAM, I PRESUME

Or

A SECOND PIECE OF VANITY

I could hardly believe my eyes when I first spotted it hidden away in the dark interior of an enormous hollow Baobab tree standing on the southern bank of the lower Zambesi, deep in Portuguese East Africa. It seemed too incredible that no one had ever spotted it before.

QUENTIN KEYNES –

DR LIVINGSTONE’S MONOGRAM, I PRESUME

In a chapter contributed to Rowan Cashel’s book by Quentin Keynes, the author describes finding David Livingstone’s monogram carved into the bark of the inside of a hollow baobab. The authenticity of the find was verified by David Livingstone’s grandson, Dr Hubert Wilson, who was shown a flashlight photograph of the monogram, the characteristically looped ‘D’ and ‘L’ of the missionary-explorer’s signature.

It all started with Keynes’s chance acquisition in an auction of a four-page letter written by Livingstone on 25 May 1859, and deposited ‘in a bottle ten feet Magnetic North from a mark + cut on the beacon.’ This acquisition started Keynes on a decision to retrace the explorer’s six-year Zambezi Expedition of 1858-1864, and in this he was accompanied by two friends.

The search eventually led to a Senhor Ferrao, whose grandfather had known Livingstone well. Ferrao mentioned a hollow baobab where Livingstone had camped near Shiramba, and Keynes narrates:

It was about three miles above Shiramba, and an immensely wide baobab, easily distinguished from others along the way by a narrow slit in its trunk. The slit provided a doorway taller than a man, and all three of us were able to walk upright through it into the tree’s dark interior. Here we found a perfect natural shelter, which I estimated to be over 30 feet high and perhaps 30 feet around.

Excitedly I peered around for initials. There were several newly made ones, and some indistinct – rather older – marks. But nothing that looked remotely like ‘D.L.’ Then I turned to face the entrance way – and there, a foot or so from the edge of the slit, was the mark that I immediately deciphered as the work of David Livingstone from the characteristically looped ‘D’ and ‘L’ of his signature that I had long since noted on my bottle letter. I could see it had been cut a long time ago from the blackness of the indentations.

“Dr Livingstone’s monogram, I presume?” I said to my astonished companions.

In camp that night I searched through a printed copy of the explorer’s Zambezi diaries, and found an entry that clearly and indisputably confirmed my discovery. Under the date September 16th, 1858 – it was now August 1958 – I read:

“We wooded at Shiramba, about four miles above the spot pointed out as the great house… I walked a little way to the southwest and found a baobab which Mr Rae and I, measuring about three feet from the ground, found to be 72 feet in circumference. It was hollow and had a good wide high doorway to it. The space inside was 9 feet in diameter and about 25 feet high. A lot of bats clustered about the top of the roof and I noticed for the first time that this tree had bark inside as well as out.”

It seems evident from the last sentence that Livingstone had been playing around with his penknife on the inner surface of this strange hollow tree, and that he had, probably without thinking much about it, soon manufactured his perfect monogram.

This contribution by Quentin Keynes raises the question: Did Livingstone further indulge his vanity by carving his initials or monogram on any other trees? It would certainly seem that when he ‘indulged in this piece of vanity’ on Livingstone Island in 1855 it was not to be the last time that he did so!

SORORO’S TREE

The following story from Rowan Cashel’s book was contributed by NJ (Jack) Brendon, a retired District Commissioner.

Many baobabs provide shelter to the tribesman, like the one known as ‘Sororo’s Tree’. This giant stands alone beside a path in the Mutoko District of Zimbabwe’s northeast, and the people of that area would spend a night in its roomy interior when they were travelling. It is big enough to accommodate 20 or more, and the trunk has a natural doorway plus several holes that serve as ventilators. One evening a man named Sororo was travelling through the country with his wife and three children. They reached the tree at about sundown, and as it was too late to travel on to the safety of the next village, they decided to spend the night in this recognized resting place. They made a small fire, and the woman roasted some monkey-nuts, then, having finished their meagre meal, the family lay down to sleep.

They were tired after their long journey, and did not stir when the fire grew cold. It was then that the lion arrived. He was old, and was worried by the quills he had received in his foreleg a month or so before when he had tried to kill a porcupine. He had tried to bite these quills from his leg, but had only succeeded in making matters worse, and now he was painfully lame. Often during the past year he had gone hungry, and now his recent injury had prevented him from killing for several days. As he passed the baobab a slight scent of humans wafted towards him. Hunger drove out any natural fear that he might have had. He prowled slowly round the tree, then saw the opening, and went inside.

It was some days before the fate of the travellers was discovered, and then the engorged animal was tracked down and shot. Since then the tree has been shunned as a place of refuge. Charms and an ornamental axe were found in the tree some months later, and this gave rise to the rumour that a witch had taken up residence in the dark interior.

To be continued.

In Retrospect by Lyn Mullin (Cont.)

SYSTEMATIC ARRANGEMENTS

A ROOTNOTE from Kim Damstra in TREE LIFE No.118 (December 1989):

Everyone seems to understand basic zoology. If asked to arrange a frog in the progression jellyfish, shark, lizard, bird, they will put the frog between the shark and the lizard. But if asked to put the Bignoniaceae (jacaranda family) into the sequence Strelitziaceae (strelitzia family), Caesalpinioideae (cassia family), Rubiaceae (gardenia family), they fall apart, as if they were being asked to translate ancient Arabic. And yet it is not very difficult, certainly not beyond any of us, if we know three easy rules:

(1) All parallel-veined leaves (e.g. Strelitzia) are conventionally placed before net-veined leaves (cassia, gardenia, and jacaranda).

(2) Net-veined leaves with separate petals (think of a cassia flower) are placed before fused petals (visualize a tube-like gardenia and jacaranda).

(3) Fruit that sits below the flower (remember a gardenia, where the remains of the flower remain on the end of the ripening fruit) is considered a more advanced feature than fruit that develops within the petals (as in a jacaranda).

So, on this basis, the Bignoniaceae (jacaranda family) falls between the Caesalpinioideae (cassia) and the Rubiaceae (gardenia).

One eventually gets to know where to find the biblical books by their “almost” chronological sequence, yet, as we are always consulting books like Trees of Southern Africa (Coates Palgrave), it will help us a lot to get a basic idea of how things are arranged – it will also open up the arrangements in most of our southern African herbaria, which follow the arrangement of the botanists Engler and Prantl. This is not a real classification, and does have a couple of flaws.

Mail a cheque for $400, made out to the “Tree Society” to PO Box 2128, Harare giving full details of your name, postal address and email address and you will be including in the mailing list pending confirmation of acceptance of membership.

MARK HYDE CHAIRMAN

MARCH 2002, No. 265

As before please confirm with any of the committee members that the scheduled outings and walks will actually take place. See the back page for phone numbers.

The annual subs are due on 1st April and unfortunately with all our costs spiralling upwards so rapidly, an increase to $400 is unavoidable.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday 6th March. Botanic garden Walk

Meet in the car park of the Botanic Garden at 4.45 for 5 p.m. where we will meet Tom and continue with the Rubiaceae family.

Sunday 17th March. The Ruwa Scout Park should be a quiet and peaceful spot for our March outing. There is no entrance fee but a donation would be appreciated, so please bring something with you. Directions: Take the Mutare Road out of Harare. The entrance to the Scout Park is on the left opposite the 20.5 km peg. Bring your lunch and meet at 9.30 a.m.

Saturday 23rd March. Hosts for Mark’s walk this Saturday are Rob and Gillian Smith who have planted over 300 indigenous trees on their property in Greystone Park, – a private arboretum – which will be very interesting. Directions: From the Borrowdale Road turn right into Harare Drive, then left into Winchcombe Road, and the first road to the right is Farnborough Close. Rob and Gillian live at No. 3; meet at the house at 2.30 p.m. There may not be room for all the vehicles inside but there will be a guard on duty outside on the road.

Easter March 28th to April 2nd. If you are interested in taking part in the trip to the Matopos please phone Maureen Silva-Jones (phone numbers on back page). We have very little time to arrange this trip so please phone now if you wish to come along. Details will be available when you phone.

Tuesday 9th April. Botanic Garden walk

N.B. Date to be confirmed depending on the possible trip to Matopos.

Sunday 21st April. To Sonya O’Donnell in Marondera.

Saturday 27th April. Mark’s Walk

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Phone Jonathan if you are interested in the possible trip to the eastern Matobo area over Easter.

No arrangements have been made for March. Contact Jonathan Timberlake if you would like to organize a future outing. His telephone numbers are 09-286529 or 285761 (tel. fax) or email timber@telconet.co.zw

Members of the Bulawayo Branch recently bade farewell to Eric and Ursula McNair who were shortly due to leave for Portland in UK. In his farewell speech Jonathan thanked Eric for all he had done for the Tree Society. His quiet and wise council will be missed.

BOTANIC GARDEN WALK: 12 FEBRUARY 2002

THE FAMILY HAMAMELIDACEAE

With Tom away on business, the assembled members decided to do their own thing and we are very grateful to Meg Coates Palgrave for suggesting an interesting topic, which got us started. She suggested looking at Trichocladus ellipticus subsp. malosanus, also known as the White Witch-hazel, in order to establish whether it has spiral or alternate leaves.

The family to which this taxon belongs, the Hamamelidaceae, is known as the witch-hazel family. It is not a family we have to think about often in Zimbabwe. Trichocladus ellipticus is the only species in the family which occurs with us and it is confined to the Eastern districts where it is to be found as a forest understorey shrub or tree or along streams and rivers or in swampy places (I have never seen it and have simply taken the details from Coates Palgrave – the book).

The Hamamelidaceae is a woody family of about 80 species; the species are mainly tropical but some occur in intemperate regions. In Cronquist’s classification, the family occurs in the order Hamamelidales with such families as the Platanaceae (i.e. Plane trees) and Myrothamnaceae (this contains the Resurrection bush, Myrothamnus, which is so common on our granite kopjies).

This species has spherical clusters of flowers borne on a peduncle and bears yellow petals. Other features of this tree are the brownish, stellate hairs on the young branches and leaves.

Meg’s particular question was – are the leaves alternate or spiral? This is not a distinction which we always make as we tend to lump both categories together under “alternate”. Alternate, in the broad sense, simply means that the leaves arise singly from the stem – as opposed to opposite or whorled where two or more arise from the same point or node.

In the narrow sense of alternate, the leaves lie in one plane (an example of this might be Celtis africana), whereas in a spiral arrangement, the leaves are borne all round the stem (an example of that is Pittosporum viridiflorum).

Why is the family known as the witch hazel family? According to the web, (discussing a N American species Hamamelis virginiana) witch-hazel obtains its name from the dowsers, or “water witches” who used forked witch-hazel sticks to detect groundwater. Commercial witch-hazel, an astringent liniment, is an alcohol extract of witch hazel bark.

Interestingly, on my recent trip to the UK, a species of Hamamelis (some planted species) was actually flowering in gardens – this in mid-January. It has a somewhat similar appearance to Trichocladus with dusters of dull yellow flowers and at that stage of the year, no leaves.

Mark Hyde

RYDAL COURT, RUWA 20th January 2002

Our first Sunday outing of the New Year was to the home of Tony and Jo Alexander, a smallholding tucked between the main road and the railway line not far beyond the Ruwa Club. It was astonishing to see the wealth of tree species that less than 25 ha accommodated, thanks to a diversity of soil and habitat types and nearly 50 years of conservation of the indigenous flora. It was also disturbing to see the invasion by exotics that had occurred, and to realise the amount of effort and expense that would be entailed in eradicating them. Ageratina formed thick clusters along the watercourse, together with a large species of Agave, Guava saplings were everywhere in the drier woodland, while Lantana scrambled in the undergrowth in riverine forest and woodland alike.

Rob Burrett led us in his unique schoolmasterly style. “Pick a leaf! Do nothing with it until I tell you! Now crush it and sniff! If you do not recognise the species you will be punished by listening to a five hour tape of a Nutty Professor!” He also taught us a slightly different approach to tree taxonomy. Never mind leaf characteristics. Can you eat it? What does it smell like?

As to the edible qualities of trees, we all sampled and some of us enjoyed the fruit of Syzygium species that dominate the property, mainly Syzygium guineense, with occasional Syzygium cordatum. They lived up to their common name of Waterberry; they formed a dense forest on the banks of a small stream, and also grew in groves in the adjoining woodland, and they bore large numbers of purple berries with a sweet, white flesh but a rather astringent skin and a large stone. We learned that the berries make a pleasant jam and a good red wine, and had the opportunity to sample Rob’s’ jam made from the related species, Syzygium paniculatum, the Australian Brush Cherry, at lunch time. It was much nicer than some of the concoctions he has inflicted on us in the past.

Two of the most palatable wild fruits of the Zimbabwe highveld are those of Vangueria infausta, the Wild Medlar, and Vangueriopsis lanciflora, the False Wild Medlar. So popular is the fruit that we hardly ever see it on our walks. As the names imply, the two species are very similar, but conventional wisdom in the Tree Society is that they can be distinguished because “Vangueria is hairier”. Hairier than what? Nobody ever seems to agree. Rob propounded a novel differentiating characteristic and illustrated it by reference to adjoining specimens of the two species. The midrib of the leaf of Vangueriopsis is raised above the upper surface, and the leaf will not fold readily along its midline. In Vangueria, the midrib lies in a shallow groove and the leaf folds easily. “Vanguesia folds easier”?

An unusual species seen was Olinia vanguerioides. There was a very large tree growing on an embankment above the watercourse, and a few smaller specimens nearby. It had no fruit visible, and it is unlikely that the fruit would be edible anyway as the tree rejoices in the name of the Rock Hard Pear. It is an Eastern Highlands species that is sometimes found along the main watershed. The species occurs only in Zimbabwe. To the south and the north, it is replaced by Olinia rocketiana and the two names may be synonymous.

As to smells, we sampled the delicious scent of Heteropyxis dehniae, the Lavender Tree. The scent is produced by secretory cavities that can be seen clearly in the leaf blades, in the interstices of the network of veins. The leaves also have domatia, which appear as small rounded nodules, up to 2mm long, on the upper surface of the leaf where the lateral veins join the midrib. The nodules act as shelters for friendly mites that clean the leaf surface and defend it against damage from plant-eating mites; we saw one minute red mite that emerged from a pit on the under surface of the leaf to see what we were doing to its home.

We also tested the aromatic characteristics of the leaves of Pittosporum viridiflorum, of Heteromorpha trifoliata, the Parsnip Tree (Parsley Tree in South Africa, do both plants smell the same?), and of Pavetta gardeniifolia, which is the smooth-leafed, non-poisonous Pavetta. The last-named species was quite common, and some trees sported delicate clusters of cream coloured flowers that were very sweetly scented. One of the diagnostic characteristics of the Pavetta species is the presence of pinhead black nodules that harbour bacteria scattered through the leaf blades. We were told that experiments have shown that the plant will not grow without the bacteria, but we wondered how the bacteria are transferred from the leaves of the parent plant to the seedlings that it generates. Do they also colonise the flowers and seeds? Does anyone out there know?

Of course, we all recognised the strong scent of crushed Lantana leaves. This invader was everywhere, but there were a surprising number of different colour varieties; the common red, a bright orange, occasionally a delicate pink, and white, all equally vigorous. What a pity it is such a pest, because it does make a lovely show. It can be distinguished from the indigenous and innocuous Lippia by its more pungent scent and its thorny stems.

For the unpleasant scents, Clerodendrum glabrum certainly took the prize, but Maytenus undata was not too far behind. The latter, known as the Koko Tree (why?), is apparently well known for its small fruit by the boys of Peterhouse, who call it Bush Muesli. And as we walked through the woodland, we had to remind ourselves that the occasional whiff of lavatories was not the result of flatulence afflicting our walking companions but indicated the presence of otherwise unnoticeable Parinari curatellifolia.

Without Mark Hyde to encourage us, we paid little attention to the small flowering plants that abounded in the woodland, some indigenous, some escapees. However, we did find a group of Hypoxis in flower, a lily-like plant that is becoming very scarce around Harare because the bulbs are reputed to be of value in the treatment of AIDS.

One of the showpieces of the property is an enormous, spreading Erythrina abyssinica of great but uncertain age. The stragglers relaxed in its shade and on its exposed roots while the enthusiasts filed off through the long grass (watch out for snakes) to look at an area of Acacia woodland; Acacia sieberiana, recognisable by straight thorns, very small leaflets and a peeling, papery bark, the Paper bark Acacia. Except that one beautiful, large, flat-topped specimen had plain grey rough bark. As Lyn Mullin pointed out last month, bark characteristics may be a pointer to the identity of a tree but are not reliable. And finally, we visited a small patch of miombo with an unseasonable red flush of leaves on the tops of the trees.

We rounded off the day with an unusually late lunch under the trees at the entrance to the Alexanders’ house, and a last foray through the woodland by the die-hards, which yielded even more species but nothing too exciting.

J.A.L.

WOOD CHARCOAL ANALYSIS

My attention was drawn to the subject by several articles in the S.A. Archaeological Bulletin where in studies mainly to do with past climatic changes, historic charcoal fragments, 10,000 years old and even older, were being identified to tree species level.

Having an interest in trees and quoting Meg Coates Palgrave “All trees have labels on them telling us what their names are, all we have to do is to learn to read the labels.” I determined to discover what a piece of charcoal could offer in a way of a label, but first some basics of plant anatomy.

Broadly, in the woody tissue of a plant – the mature xylem – there is the development of specified cells, namely rays, vessels, tracheids, parenchyma and fibres, each with different roles to play, but all with lignified walls which retain their shape, and after being charcoaled, able to endure to passage of time. In addition, there other features such as vestured vessel pits and sieve plate that can be seen with the aid of a Scanning Electron Microscope to give, according to some authors, up to 163 anatomical features to be considered. It is however, the arrangement and relationship of these cells to each other that distinguish one species from another.

The rays, as the name implies, radiate ribbon-like outwards from the centre, the cells resembling bricks in a wall and can be one brick wide – uniseriate – or three or four – multiseriate – and can vary in depth. These brick like cells can be laid with the long axis horizontal – homogeneous – or on end – heterogeneous.

The vessels are longitudinal tubes and vary in density of numbers, in diameter size, and distribution. They can be solitary or paired in multiples.

Tracheids are conducting tubes in the xylem, and are an important constituent in the gymnosperm plant division. The parenchyma cells, like the rays, are brick-like but run longitudinally one brick on top of another. Their arrangement in relation to the vessels and rays are an important diagnostic feature. Fibres are generally small celled and play a supportive role. These features can be viewed in three dimensions, the transverse section across the length being the most important. The longitudinal radial section is at right angle to the direction of the rays and thirdly, there is the longitudinal tangential section at right angle to the radial section.

When wood is reduced to charcoal the volatile resins and tars are driven off leaving a porous skeleton of the lignified walls and as the scale of the cell size is sub-microscopic, various techniques have been used in the examination.

The simplest effective method is using a microscope with reflective light on a dark field. (Light shines down onto the specimen and is reflected up to the eye). The sample of charcoal is fractured by hand into the three different dimensions and a description given under the headings of rays vessels and parenchyma. Ideally, for comparative purposes, a photographic record should be obtained.

A collection was started of woodland species that could be used at some time to identify, by comparison, different species in various historic charcoal collections. Samples were usually taken on Tree Society outings so as to be authenticated by the fundis and were confined to dead branches of about 10 to 25 mm diameter: the sort of material that local fuel wood harvesters gather today where woodlots are available. Carefully labelled, the samples were stored and when dry small pieces were wrapped in tin foil and heated on a hot plate (out of doors) until smoke ceased being given off.

The results have produced a bewildering diversity of cell arrangements and different species certainly do have different labels. Some historic species have been matched with their present day counterparts, others not, it is an ongoing experience. I am very grateful to Rob Burrett for providing me with a list of trees associated with a number of archaeological sites, and in particular, giving me access to his charcoal collection from Gosho Park for what is a fairly destructive process. Thanks as well to Lorraine Swan and Carolyn Thorp of the National Museum for their interest and providing further more material for examination. I am certain some Interesting finds will be forthcoming.

Derek Henderson.

BAOBABS IN MY SOUP continued

By Lyn Mullin

CHIDZERE’S TREE

(From Rowan Cashel, with input from John White and Robin Hughes)

Long, long ago, when Chidzere was Chief of the Urungwe region of the Zambezi Valley, another Chief, Dandawa, arrived with his followers in search of salt. They came from a country to the north called Guruuswa, or its variant, Gunuuswa, meaning ‘long grass’. Some believe this country to be Tanganyika. Dandawa claimed Chidzere’s land, and a pitched battle ensued. With vastly superior forces, Dandawa got the better of his rival, and Chidzere’s people were forced to flee to the north, across the Zambezi. Chidzere refused to accompany them, asserting that he was the lawful chief. “My children”, he said, “I, am about to die of suffocation, but my flesh will not rot and become infested with worms, nor will it become of the soil”. Thereupon he threw himself to the ground, raised both legs in the air, and beating the earth with both palms, turned himself into a baobab.

Chief Dandawa, now in sole control, remained in the area, but the land was soon devastated by famine, and the people decimated by hordes of lions and hyaenas. Such was their plight that their midzimu (ancestral spirits) were assiduously consulted and propitiated, and reasons sought for their dire misfortunes. The reply was direct and clear. Dandawa had gone to war with Chidzere, the legal chief, taken his country, and driven his followers away. Dandawa lost no time in sending an envoy across the river with the plea that Chidzere’s people return. This they did after consulting and appeasing Chidzere’s ancestral spirits, which made it possible for both factions to live in harmony.

After the construction of Lake Kariba, a grand scheme was proposed for growing sugar on a large scale in the Zambezi Valley below the Chirundu Bridge. This was to be irrigated by water from the lake, but in the event the scheme proved a failure because of unsuitable soil. But before the scheme could be undertaken it was necessary to move Chief Dandawa and his followers to the escarpment above the new lake, a considerable distance from the famous baobab.

From the time that Chidzere had turned himself into a baobab, and before Dandawa was moved, propitiation ceremonies were held regularly at the famous tree. It was customary at these functions to pour specially brewed beer and thin gruel into small pots at the base of the tree. Such occasions included drought, ‘misbehaviour’ by lions and hyaenas, outbreaks of plague, and so on. At harvest time the people again assembled when the ‘Tree Priest’ gave thanks and praise to the spirit for his beneficence.

Up to the time that Dandawa’s people were moved from the valley in 1958, Lazarus Chidoma was responsible for sacrificing to the spirit; he claimed to be the eighth incumbent since Chidzere had turned himself into a baobab. He had in his possession two long, well crafted spearheads without hafts that he kept wrapped up in a length of black cloth. These, he said, had belonged to Chidzere, and were of Vambara workmanship.

There is an interesting story relating to Chidzere’s tree in recent times. It used to have a large opening about the size of a door in its hollow trunk, and inside was a large and productive beehive. Once a year a man named Kanhema, a descendant of Chidzere, used to gather all the people at the baobab, and they would sit quietly while he went inside, and, without the use of smoke, would take honey without being attacked by the bees. He would then divide the honey among the people. However, in December 1923 a man named William Kamkure decided to go into the tree and take all the honey for himself. As soon as he entered the tree he dropped down dead. A passer-by noticed his feet protruding from the hole, and, on investigation, discovered the body of Kamkure. Although he had not been attacked by the bees, it was found that his skin had virtually all peeled from his body. The death was taken by the people as a sign that the spirits were angry that anyone other than Kanhema should try to rob the hive.

NOTES ON SOME HISTORIC BAOBABS

These notes appeared in Rowan Cashel’s book as a contribution by GL Guy, who served with the Forestry Commission for many years before joining the Department of National Museums & Monuments. Guy’s contribution is reproduced with some editing, mainly to give tree measurements in metric units, and to update place names.

Ever since the early explorers in southern Africa first saw baobabs, their size and probable age have excited comment and speculation. Adanson, for whom the genus was named, was the first to speculate: he worked on the basis of annual growth, and decided that a tree in Senegal must have been some 5150 years old. Andersson, late in the 18th century, tried to calculate the rate of growth from the time taken to cover some initials carved on a tree, and he, too, arrived at an age of 5000 years. David Livingstone also entered the controversy; in 1853 he counted the growth rings in a tree in Botswana, and arrived at a figure of 83 rings per foot of radius.

Livingstone did more than speculate about their age; he measured some, two of which we have been able to locate. The first, in 1853, is on the north side of Ntwetwe Pan in Botswana, and he described it in these words: “About two miles beyond the northern bank of the pan we unyoked under a fine specimen of the baobab, here called in the language of the Bechuanas, mowana. It consisted of six branches united into one trunk, and at three feet [0.91 m] from the ground it was 85 feet [25.91 m] in circumference.” Livingstone’s calculations were not very accurate, though: he gave the diameter of this tree as 36 feet 5 inches [11.10 m], the actual figure being 27 feet 0.7 inches [8.25 m], and in his Journal he quoted 20 rings per inch, and gave the age as 4360 years. The tree was fairly easy to find, for Livingstone went on to say that they outspanned at Gootsa Pan, which was still known by that name when we visited it in September 1966. At “three feet” from the ground the tree now measures 80 feet 3 inches in circumference [24.46 m], an anomaly that I will attempt to explain later. For the present it will suffice to say that the last 100 years have seen a gradual drying up of the country. Livingstone estimated the circumference of Lake Ngami as 39 miles [±63km]: it has been completely dry on occasion in recent years, and the Botletle River (Dzouga of Livingstone) is no longer the populous river highway of 1853.

James Chapman, a year or so later, followed Livingstone’s spoor, and said of this same tree near Gootsa: “The dimensions, which we took with a measuring tape, proved its circumference at the base to be 29 yards [26.52 m]. This confirms Livingstone’s measurements, assuming that Chapman ran his tape round the tree a few inches lower. The base is heavily buttressed, and could not easily be circled.

On the tree are carved “J. Jolley” “1875” “O.B.”, and I wrote to EC Tabler in West Virginia about these. His comments were that he was interested to know how Jolley spelt his name, that the “1875” must have been carved in the year of Jolley’s death, for he died of fever at Pandamatenga in August that year. “0. B.” was most likely Oswald Bagger, a somewhat flamboyant Swede, who was near the Victoria Palls in 1878. Jolley is still commemorated by Jolley’s Pan on the old

Pandamatenga Road, which is now the Zimbabwean border with Botswana. Had this tree been nearer a source of water it would have had far more records of early travellers carved on it: about three miles due north of it is Gootsa Pan, where Livingstone, and many after him, camped, as the surviving baobab shows. Unfortunately, for our purposes, no one seems to have left a record of the size of this tree; in 1966 it was 50 feet 10 inches in girth [15.49 m] at breast height (1.3 m above ground level), and the condition of the letters shows that it has grown very slowly, if at all, since “H.V.Z. 1851”. I have been unable to find out very much about Harry van Zyl, other than that he was a hunter. The ‘Green Expedition’ was one of several made by the Green brothers, Frederick and Charles. They were Canadians by birth, and travelled with such famous naturalists as Wahlberg, who was killed while hunting elephant in 1855 with Frederick Green, Chapman, and CJ Andersson, whose books are well known to naturalists and historians. The Greens were among the first white men to reach Ghanzi, and went as far north as the Chobe River in 1852. “F.W.D.” is obviously Fred Drake, a hunter and trader from Pinetown, who hunted as far north as Dete from 1873 to 1879.

We failed to find another, very much larger, tree, under which Baines and Chapman camped for several days while Chapman was ill in May 1862. We were within a few miles of it when we found a group of baobabs painted by Baines on 21 May, because he said, “a long circuit brought me, with empty pouch, to the clump of baobabs we had seen yesterday from the wagon. Five full-sized trees and two or three younger ones were standing, so that when in leaf their foliage must form one magnificent shade. One gigantic trunk had fallen and lay prostrate, but still losing none of its vitality, sent forth branches and young leaves like the rest.”

The trees are still standing, and look very much as they did in Baines’s day, except that the right-hand one, or eastern, had lost two branches; one hollow was inhabited by Barn Owls when we saw it. When searching for the tree of 101 feet girth [30.78 m] we did not know of the existence of the clump, or of Baines’s sketch, so we tried to retrace Baines and Chapman’s route from their maps and the names of the pans. With the clump as starting point we should be able to find it if it still exists.

Baines and Chapman earlier in their trip used another baobab as a campsite, and their diaries refer to it as “the big tree”. It must have the biggest they had yet seen, but its girth at 50 feet was small in comparison with some they encountered later. This tree is just off the Ngami-Ghanzi track, and is situated on the edge of a pan, and its position on modern maps agrees very closely with the latitude calculated by Baines.

He remarked that they had “found the little puddle of filthy water quite insufficient for our cattle, and as for drinking it ourselves when the wagon came up and coffee was made, nearly two thirds of the depth was thick mud.”

We measured the [diameter of the] tree at 15 inches (38 cm) from the ground, 59 feet 4 inches [18.08 m], and at breast height, 56 feet 0 inches [17.07 m]. It is hard to guess where Baines made his measurements, but it must have been above ground level because of buttress roots, and the mere fact of having to stoop low to measure. We think he must have measured it at about breast height, which is the most convenient height. This tree has obviously grown in girth, probably almost entirely because of the reserve of water afforded by the pan, which, when about full, is 100 by 90 paces in size.

To be continued.