TREE LIFE

DECEMBER 2001

A WISH FOR ALL OUR MEMBERS HAVE A VERY HAPPY CHRISTMAS

AND MAY THE NEW YEAR BRING PEACE.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday 4 December Botanic Garden Walk Meet in the car park of the Botanic Garden at 4.45 for 5 pm where we will meet Tom and start on that challenging family – Rubiaceae..

Sunday 9 December. We are very grateful indeed to Bill Clarke who has once again agreed to host our Christmas social at his beautiful property Val d’Or in the Arcturas area.

There is a special treat this year. After tea, which will be served at 9.30, we will set off for another session of Tree Bingo with Tom Muller in the lead.

December 22. Mark’s walk is moved to January 5th.

Saturday 5 January (Moved from December 22). Mark’s walk will be at the home of Dr Peter Iliff at 7, Ernie’s Lane, Monavale, which we last visited in June 2001.

Tuesday 8 January 2002 N.B. Change of date. Botanic Garden walk

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

No arrangements have been made for December. Contact Jonathan Timberlake if you would like to organize a future outing.

A YELLOW-FLOWERING FLAMBOYANT

If you want to see something out of the ordinary take a quick trip to the Old Hospital in the Paririrenyatwa complex to see a yellow-flowering flamboyant (Delonix regia). I was put onto this tree by Derek Henderson, and I found it on the west side of the main building, more or less in front of what was the main entrance in former times. To get to the tree go into the Pari complex by the main entrance on Mazowe Street, and drive straight down towards the bottom of the road. Roughly opposite the Pari Hospital there is a car park on your left as you drive down. Immediately beyond this, take the road to your left and drive up to the Old Hospital building; as you get into the grounds bear right, then left, and you will see the tree just beyond a small car park.

Apart from the yellow flowers, there is nothing peculiar about this tree and it would pass for a conventional Delonix regia. If you really want to check that out, there is a red-flowering specimen just beyond the yellow one, which can be used for comparison – but don’t wait too long because the flamboyant flowering season will be over soon.

-Lyn Mullin

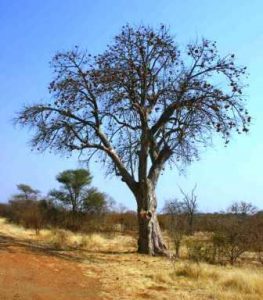

MSASAS FOUND IN SOUTH AFRICA -AN EXCITING DISCOVERY

Brachystegia spiciformis. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

The December 2000 edition of Sabonet News contains an article by Erich van Wyk and Johan Hurter announcing the first record of Brachystegia spiciformis in South Africa. The following is a précis of their article.

During August 2000, the two authors were investigating new seed sources for the Millennium Seed Bank (a collaborative project between Kew and the National Botanical Institute in Pretoria). They were in a remote part of Venda in the Northern Province.

On the second day of the expedition they were investigating a population of an endemic Combretum, C. vendae and while venturing deeper into the Soutpansberg they noticed a “new turn-off” leading off into unexplored territory. They had no time to explore it that day and it was not until late on the third day they decided to investigate it.

The discovery is reported as follows: “Suddenly, after about 5 km, the vegetation started changing, becoming more mesic in nature. As we came over a slight rise, the most magnificent sight in Africa greeted us: there in front of us and in full spring colours was a valley of thousands of B. spiciformis. As the sun was setting, we hastily decided to collect fertile herbarium vouchers and left the scene only after the last rays had disappeared. Overjoyed by the find, we reached base camp at about 20:00″.

The discovery, the authors continue, is a most significant find, extending the distribution range of B. spiciformis southwards across the arid Limpopo valley. Palaeopalynological evidence suggests the presence of this vegetation type as far south as Naboomspruit dating back to 19 000 BP. It is believed that during geological times, Miombo woodlands had expanded and contracted in response to climatic change.

The ecology of the population is being studied and the authors hope to present more detailed technical information in a formal publication.

-Mark Hyde

TAMBOTI – SPIROSTACHYS AFRICANA.

Spirostachys africana. Photo: Rob Burrett. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Many incidents in Sir Percy Fitzpatric’s book “Jock of the Bushveld” made lasting impressions on me as a young boy, not least of which was his account of the practical joke he and his group of ox waggon transport riders played on an unwelcome guest who had joined up with their trek. They presented him with a plateful of Tamboti jumping beans for his grub! He got the message and promptly departed.

It was many years later that my interest in the Tamboti tree became real when I came into contact with it in the Lowveld and was able to witness the wood with its wonderful attributes and aroma and the jumping bean phenomenon.

Spirostachys africana is not an uncommon tree in the S.E.Lowveld. It occurs mostly on heavy soils along water courses. Deciduous and of medium height, the bark is characterisically rough and black. The milky latex can cause severe irritation to the skin and eyes. Furthermore, it is not used as a cooking fuel because it imparts unpleasant taints to the food. The species enjoys a degree of built-in protection against overuse by humans. Kudu browse it, but hunters are careful when dressing a carcass in Tamboti country not to allow the rumenal contents to spoil the edible cuts.

Tamboti wood is highly prized for furniture and ornaments but large workable trees are rare. The wood is very distinctive, the sapwood being a creamy white which contrasts sharply with the heartwood which is fine grained, a rich brown colour as well as extremely hard and durable. It also has a sweet scent, the sandalwood scent, which it retains for years and years. It is a difficult timber to work, the sawdust causing severe irritation to the eyes and nose, but worse is the fact that most trunks have internal cavities usually contaminated with termite workings, the resultant grit wrecking sawing and planing tools.

During severe droughts, I have seen evidence of porcupines gnawing the bark often to the extent of ringbarking the tree. However, I could never find older wounds which points to this habit as being very occasional or to the bark being able to regrow over the damage fairly quickly.

But to the amateur bundu lover it is the jumping bean phenomenon which endears the tree in the main. Tamboti flowers in September and the pea sized seeds develop in three-lobed capsules which fall, when mature in November, to the leaf litter below. If you stand by a copse of Tamboti trees on a hot November day you may hear a distinctive rustling in the litter and if you look more closely you will see some flicking in the litter due to some seeds jumping intermittently. Collect some of these jumpers and place them on a plate in the hot sun and the jumping becomes more invigorated. Open one carefully and you will find a small larva whose body suddenly contorts causing the bean to jump. Evidently, a small moth lays its eggs on the developing fruits and on hatching, the larvae penetrate the fruit capsule where they consume the kernel material and finally pupate in the leaf litter. The moth emerges a year later and the cycle is repeated.

So why the jumping? I think this enables the insect within the seed capsule to work its way down through the litter where it can enjoy better protection for the duration of its lifecycle.

All in all the Tamboti tree has a lot of interest going for it.

-JHWilson

BOTANIC GARDEN WALK: 6 NOVEMBER 2001

Today’s subject was not a particular family or genus but the trees of rocky places. I would have thought that these had little in common but Tom pointed out that many of them have smooth bark. Perhaps this is because of the absence of fire which means that there is no need for a thick ridged and fissured bark.

The first pair of species has smooth bark which is also strikingly peeling. These are Albizia tanganyicensis (Paperbark albizia) and Commiphora marlothii (Paperbark commiphora). These are of course quite unrelated: the Albizia is a legume with 2-pinnate leaves and typical legume pods while the Commiphora belongs to the Burseraceae, has 1-pinnate leaves and fleshy, spherical fruit. Both occur in rocky places and I am ashamed to admit that on occasions when the tree is leafless I have mixed the two up – suddenly realising that my so-called Commiphora had pods!

The Albizia is fairly common in rocky places but only at low and medium altitudes (Tom mentioned that it just reaches up to near Harare at Christon Bank) and is often associated with Erythrina livingstoniana. Lyn Mullin mentioned that it also occurs in Kalahari sand at Gwaai Forest Hill. The bark is often pale to almost white in colour.

The Paperbark commiphora is also a tree of rocky places. Its bark is more green than the albizia. It too is common in the right habitat and again prefers medium and low altitudes although I see from my records it has reached 1460 m in the Central Division.

Another natural pair of species is the two sterculias. Sterculia quinqueloba reaches the edge of the African plain, just north of Harare and can be found from there all the way down to Kariba. This is the one with big leaves and small fruits (S. africana is the other way round). The bark is smooth and pale grey or sometimes brown.

Sterculia africana. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Sterculia africana has bark which is more liver-coloured, but which is also strikingly smooth. This species is quite general in the lowveld and is not confined to rocky places but sometimes occurs there. The trunk may occasionally be somewhat swollen and the whole effect makes the tree look like a baobab.

[Incidentally, on a similar subject, in G. Silundika Avenue, near the Fourth Street carpark is a row of planted trees: Brachychiton discolor. These look very similar to sterculias, in the flowers, the fruitsand the leaves and indeed they do belong to the same family, the Sterculiaceae. They also possess slightly swollen stems and like Sterculia africana have a hint of the baobab about them].

Other species of rocky places with smooth bark we noted included:

Gyrocarpus americanus (the Propeller tree). This is fairly common in the lowveld; it has lobed leaves and fruits with a marked lateral wing which sends them twirling round as they fall. This is a very widespread tree occurring not only in Africa, but also in S America and Australasia. The African plants obviously differ slightly from the rest and have been rewarded taxonomically by calling them subspecies africanus.

Afzelia quanzensis (Pod mahogany). Another species with smooth, greyish bark, although this is not confined to rocky places.

Kirkia acuminata. Tom described this as occurring on every hill in the middle and lowveld. The bark, although often smooth, can actually be quite rough. The wood is hard and blunts saws with its high silica content.

Lannea discolor (the Livelong). Common at a wide range of altitudes and also a wide range of habitats and by no means confined to rocky places.

Entandophragma caudatum (Wooden banana). This well-known species often occurs in rocky places but is not confined to them.

Schebera trichoclada (Wooden pear). Another grey-barked species occurring frequently in rocky places. In the example at the Gardens the bark was actually not particularly smooth.

Brachystegia glaucescens (Mountain acacia). This is the tree of rocky places par excellence. As we know the bark is fairly smooth and grey although not perfectly so.

What exceptions are there?

The rule of smooth bark in rocky places is by no means foolproof. Apart from the Kirkia and Schrebera mentioned above, species of Erythrina occur in rocky habitats and may have thick, corky bark which may further be adorned by prickles on stout bosses.

Other counter-examples are species of Terminalia, e.g. Terminalia stenostachya, which have very dark bark which is strongly vertically ridged.

All in all a very interesting walk exploring an aspect of trees which was a new concept to me. As usual, our thanks go to Tom for providing us with a stimulating walk.

-Mark Hyde

INTERESTING ALIENS AT ST GEORGE’S COLLEGE 27 OCTOBER 2001

My Saturday afternoon walk which had been planned for a farm near Lilfordia School was unfortunately cancelled at the last minute because of two incidents nearby, one of which was at the particular area we were due to visit.

At very short notice therefore, Fr. Hugh Ross was contacted and an alternative venue of St George’s College arranged.

A surprise and welcome visitor was Hugh Glen from the National Botanical Institute in Pretoria who is visiting Zimbabwe as part of a Sabonet initiative.

The main aim of the walk was to re-visit the extraordinary crop of E Districts trees on the top of Hartmann Hill near a small water tower. This corner of the school grounds abuts the grounds of the National Botanic Gardens and is mainly ordinary msasa woodland.

At the top of the hill below the water tower, water cascades out and runs a short way down the hill before disappearing underground. A moister-than-usual environment is thereby created and around the tower grow a number of interesting species, some of which are more reminiscent of the E Highlands than the Harare area. When I was first shown these species a few years ago, I thought that someone had tried to create an E Districts garden, but both Father Ross and Rob Burrett have assured me that these trees have not been planted.

The “E Districts species” together with some comments on their Zimbabwean distribution are as follows:

Macaranga capensis. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Macaranga capensis. A fine specimen occurs near the water tower but we also found a small one at the base of the slope in dry woodland. I understand that this is planted in the Botanic Gardens and I suspect that this is the source of this species. Tom later confirmed that this does behave as a weed in the Gardens.

Phyllanthus ovalifolius. The native distribution of this species is again the eastern and southern divisions of Zimbabwe. It is a semi-scrambling, woody species which forms large bushes several metres high and has fine pinnate-looking leaves. Although there is one up by the tower, it is quite common in the grounds of St George’s College and there are many fine specimens on the other side of the fence in the Botanic Gardens. Again, I suspect the Botanic Gardens are the source of this species.

Polyscias fulva. This is an E Districts forest pioneer. There is a fine tree by the water tower. It is again planted in the Botanic Gardens and behaves as a weed there (again, per Tom).

Sapium ellipticum. Another E Districts forest species. Again, this is planted in the Gardens and escapes freely there. This might be the source or alternatively it might have a nearer source. It is planted at the base of the hill near the school buildings and in the woodland between the two places we saw a number of small specimens of Sapium ellipticum which looked self-sown.

Toddalia asiatica. Another common E Districts species but this is not confined to there but also occurs on some outliers, for example Hwedza Mountain which would probably be the nearest point. This species was also seen at the bottom of the hill. Like Sapium this could have originated from the Botanic Gardens or possibly the College itself.

Another species by the water tower is Maesa lanceolata. This is a high rainfall species which is very common in the E Districts but is certainly not confined to there. We come across it from time to time around Harare so its presence on the hill is not particularly surprising. Possibly the perennial water supply helps it.

Also nearby was the rhus with small, shiny leaves which we call Rhus natalensis. Tom mentioned that this also freely seeds itself around the Gardens.

In addition to these, there are three exotics

Homalanthus populifolius (Queensland poplar). This is commonly planted in Harare gardens and is occasionally naturalised around Harare but in a rather scattered way. I suspect that the size of this specimen is supported by the perennial water flow.

Ligustrum lucidum (a species of privet). Again, commonly planted in gardens and occasionally escaping, usually in my experience by rivers and streams.

Solanum mauritianum (Bug tree). A common weed around Harare; its presence here is I suspect not particularly significant.

In conclusion, it seems that the Botanic Gardens are acting as a source of species of alien origin (alien to this part of Zimbabwe even though they are native in other parts) which are spreading into the grounds of the adjacent College, assisted in some cases by the perennial water provided by the overflowing water tower.

-Mark Hyde

ELEPHANT OVER-POPULATION – QUESTIONS.

I am sure there will be readers of Tree Life who can help me understand the issue of elephant population growth rates and the factors that might cause them to vary.

What confuses me is this. When we limit a population of elephants to a game park like Gona re Zhou, they appear to breed relatively quickly to numbers which greatly exceed the carrying capacity of the land and its vegetation and this results in the almost total destruction of the woodland, certainly that within reach of water.

I quite understand that, if the elephant had free access to migrate seasonally away from the lowveld to the better watered areas, this would relieve the pressure and allow the vegetation to repair towards some sort of balance. Given that the breeding capacity of elephants is so great as we appear to have seen in the Gona re Zhou, why did they not overpopulate the whole land in generations past when they had the run of the whole African continent and before Man was anything of a significant predator on them? Is it possible that they did in fact overpopulate and destroy large stretches of Africa which have since been able to regenerate once their numbers were reduced by starvation or Man’s attention as the ivory trade developed?

Or was it some physiological factor associated with the better watered areas that actually diminished their breeding capacity more in harmony with the land capability? Are we saying that the Lowveld woodland is just not robust enough to withstand the browsing pressure of elephant if contained and left there to breed naturally? On the other hand it may be that the problem has been aggravated by surplus elephant squeezing into our National Parks following human pressure in neighbouring regions and that it is not entirely a problem of local breeding rates. Who knows?

In Hwange National Park there is also significant damage to woodland caused by elephant but the rainfall there is greater and the vegetation is different from that of Gona re Zhou, and perhaps more resilient to elephant damage. The problem never appears quite so bad there. On the other hand, the damage upstream of the Falls on the Zambezi is shocking and I have seen similar devastation in parts of Botswana.

Fundamental to such questions is reliable statistical data on elephant population growth rates and the degree to which they might be related to broad vegetation class.

It is clear that over the past thirty years much of the woodland in the Gona re Zhou has been devastated on account of excessive elephant browsing pressure. For those who appreciate trees it might have been better had there been no elephant there at all if there can be no effective control of numbers.

Clearly I need help in understanding the population dynamics involved and I sincerely hope readers will put pen to paper to shed light on this ecological phenomenon. Can it be that elephants are too successful physiologically at breeding and that they need Man to take off the excess since they appear to have no other predators? Or are we keeping them in the wrong places – places which physiologically promote breeding but ecologically cannot sustain them?

Lyn Mullin’s observations with regard to the flowering happenings amongst the Jacaranda trees this year attracted comments from two of our members, Alan Foot writes from Trianda Farm – “On a recent visit to Harare my eyes spent more time on the trees than on the road – very fortunately, without mishap!

It seemed to me that there were Jacarandas with plenty of leaf and fewer flowers but there were even more trees with a full flush of really glorious flowers. I am not good enough at colour to know whether you would describe the Jacaranda bloom as mauve or lavender but I fancy that the leafier trees were also paler in colour (an optical illusion?)

For some years now I have thought that there are two shades of Jacaranda and there is an excellent example of this on the 9th hole at Jumbo Golf Club where there are two trees on either side of the green and if one is fortunate enough to be on the fairway there is time to observe the difference in colour of the blooms on these two trees. As with the msasas, I assumed it was to do with trace elements that they tap but could they in fact be sub-species or just have a different genetic make-up?”

***

And from Bulawayo Norma Hughes writes –

“Here the Jacarandas all put forth their leaves first, and I too thought they were strange. However, it transpired that they were the best for many years. The Chronicle actually noticed and commented and published a photograph.

The Schizolobium parahybus was the same. I only know of one of these trees (there must be more) which is in Marimba Road, in Bulawayo. Its leaves were fully out before the blossoms came, and it too was spectacular.

Maybe the shock of having two good rainy seasons in succession was too great for everything?

The Acacia galpinii did not flower at all this year. They are still heavy with seeds from last year’s really exceptional flowering. But the Albizia are excellent. The Acacia karroo have also not put forth any blossoms as yet, in spite of two good rains.”

WITHOUT TREES

No place is complete without trees.

A home without trees is charmless

A road without trees is shadeless

A park without trees is purposeless

A COUNTRY WITHOUT TREES IS HOPELESS!

In retrospect cont. Lyn Mullin

DEATH BY UFO?

In the Mukuvisi Woodland Notes of TREE LIFE No.126 (August 1990), George Hall recorded an interesting, and puzzling, discovery:

One November I found a dead tree – nothing unusual in that, except in the manner of its demise. In full flush of spring growth, it had been struck dead with such a release of energy that the trunk had burst into flames. The furthermost leaves and twigs, whilst not consumed by the flames, had blackened and died, as in an instant of time. There was a definite point of impact at about eye level, and damaged twigs on nearby trees indicated a kind of trajectory, showing from which direction this had come.

I telephoned the Met Department. Without embellishment, I explained the death of this tree. At first the official to whom I spoke believed I was making some kind of complaint. When I convinced him that I was seeking knowledge he carefully noted my remarks, but declined an invitation to be guided to the scene. Seven days later I received a very pleasant telephone call, and it told me that they had thought about what I had reported, and considered that the cause was lightning.

Now, come an average rainy season, we get a lot of trees struck by lightning, and know what it looks like. Also, the seven days prior to my observation had been clear anticyclone, not a trace of thunder activity.

In my own mind I am satisfied that this tree was killed by a speck of meteoric dust. Unfortunately, I had not got a geiger counter in my back pocket to check radiation levels.

INDIGENOUS TIMBERS

Reference was made in TREE LIFE No.126 (August 1990) to the wood properties of Pericopsis angolensis (muwanga) and Kirkia acuminata (white syringa). The first is extremely hard and heavy – 930 kg/cubic metre compared with mukwa (Pterocarpus angolensis), which has a density of 640 kg/cubic metre. Because of its great strength and durability muwanga was a favourite mining timber in this country in the early part of the 20th century, and a great quantity of it was cut and used in the mines, which probably explains the observation in TREE LIFE No.126 that large trees are now rare. It has been used for furniture, but it is really too heavy for that purpose. White syringa timber is very attractive, and at 590 kg/cubic metre it is a bit lighter than mukwa. The main difficulty with this wood – still plentiful enough in Zimbabwe – is that it takes up silica from the soil, and this has a serious dulling effect on all cutting tools. One of the main uses for white syringa today, seems to be wood carvings, which are seen commonly at the various roadside stalls around the country.

MARK HYDE CHAIRMAN