TREE LIFE

February 2000

SUBS ARE DUE ON 1ST APRIL AND THE CURRENT UNHAPPY STATE OF AFFAIRS MAKES IT NECESSARY TO INCREASE THEM TO $120 PER

ANNUM.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday 8 February. Please note that because of our trip to Mapor the walk will be on the second Tuesday in February. Botanic Garden Walk at 4.45 for 5 p.m. We will meet Tom in the car park and continue with the Euphorbiaceae family. There will be a guard for the cars.

Sunday 20 February. We last visited Caesar Pass on the Great Dyke in 1992, so a return visit will be interesting. This is a good venue with plants that are chemical tolerant, such as Ozoroa longipetiolata. Other trees of interest which we expect to see are Apodytes dimidiata, Rapanea melanophloeos, Phoenix reclinata, Catha edulis and Securidaca longipedunculata.

Saturday 26 February. Mark’s walk is cancelled this month as Mark will be away.

Tuesday 7 March. Botanic Garden Walk.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR.

Sunday 13 February. An all day visit to John and Jill Dudman’s farm Doornoch Estate, Figtree. Meet at Girls’ College at 8 for a prompt departure at 8.30 a.m. Bring lunch and your chair, etc.

Sunday 6 March. Either to Umgusa or the Randall’s on the Victoria Falls Road to look at acacias. Meet at Girls’ College.

The following is a comment on the observation made in the write-up on the trip to Galloway Farm in Norton that Euphorbia espinosa is not usually found in the Norton area and that it normally occurs on Kalahari sands on the edge of mopane country. In my experience Euphorbia espinosa is found in a very widespread area from Norton south-westwards to Bulawayo and northwards to the Zambezi Valley, growing on all types of soils. Whereas it may sometimes occur on Kalahari sand, it also occurs on granite cyanite, basalt, shists and various types of clay, for example it is quite common on mudstone in the Hwange area. Euphorbia espinosa has a fairly drooping habit.

Euphorbia matabelensis, a related species, can be very common on Kalahari sand but again is not confined to Kalahari sand, growing in a wide variety of soils, particularly granite sand. Euphorbia matabelensis usually has a fairly upright habit.

-Anthon Ellert

TSHABALALA, BULAWAYO, 5 December 1999

This encompassed 16 Sunday souls all agog to take acacias seriously. We set off on a rainless morning (having had around 16 mm of rain the previous day) to Tshabalala Game Reserve just over 10km from the city. That day mud prevailed so we were advised not to take our ordinary cars in and only Jonathan’s 4×4 could penetrate, carrying its load of decrepitude. The able-bodied proudly walked.

Can we, who are by no means all botanists, really be excited by boring old thorn trees – even if we call them mimosas (American for Buck’s Fizz)? Some of us experience a love/hate emotion with the genus, yet they are a challenge and a fascination. Perhaps, like medicine, a thorny but interesting pathway, especially when stimulated by enthusiasts such as Jonathan today and Ian McCausland some years ago.

Today Jonathan took us straight to a place where five species exhibited themselves within a few metres. And here he began his sermon….

There are four categories of Acacia as determined by arrangement of thorns: (a) straight paired thorns, (b) paired hooked thorns, (c) scattered hooked thorns, and (d) hooked thorns in threes. Independent of this, acacias can also be divided into those with dehiscent pods (the majority) and those with indehiscent pods.

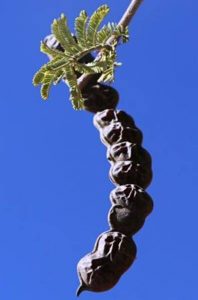

Acacia nilotica. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

The first species was Acacia nilotica (scented thorn), first described by Linnaeus from the Nile whence it spreads across Africa and into India. Its general habit or outline is V-shaped. The indehiscent pods are tough and resemble a string of beads. They rot on the ground where they fall and thus depend on animals and their faeces for propagation. Hence the distribution of Acacia nilotica tends to mirror that of livestock.

Dehiscent pods, on the other hand, simply fall from the pod while still on the tree. Flowers are in yellow balls, and the straight paired thorns come oft the nodes, being declined slightly backwards – a diagnostic trait. Young growth is pink/red and slightly pubescent, while older twigs are characterized by longitudinal splits of the epidermis.

The second species was the widely distributed Acacia karroo (sweet thorn) with a general outline like a U owing to its ascending branches. This tree gets up to about 15 m in height It has paired, straight thorns, glossy leaves with a furrow along the main rachis, and only loses its leaves for two months or so. The flowers form golden-yellow balls. There is a variant with whitish flowers (probably a separate species) found only on Bazuruto and nearby islands off the Mozambique coast, which can also tolerate occasional inundation of its roots by seawater. The pods are dehiscent, slender and sickle-shaped. This fast-growing pioneer species is very flexible in its requirements and is excellent for rehabilitating degraded land. Its life expectancy is up to 35 years – 45-50 year old specimens are exceptional. However, it has a high germination rate and can go from seed to flower within 2 to 3 years. It makes good firewood while the gum has anti-bacterial properties and is used in sweet manufacture.

The third species was Acacia rehmanniana (Silky acacia), a smaller tree that is almost endemic to Zimbabwe, growing principally on the watershed above 900 m altitude. It is characterized by its orangey bark and the feathery, soft, silky foliage. Thorns are paired and straight, the new ones being pubescent. There is a yellowish tinge to the new growth. It is closely related to, and may be confused with, Acacia sieberiana and Acacia abyssinica. The flowers form white balls while the pods are dehiscent, straight, hairless and rather like those of Acacia sieberiana, except not thick and woody. This species does not make particularly good firewood.

Acacia gerrardii. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

The fourth species was Acacia gerrardii (red thorn). This grey-haired acacia has very dense leaves all along the twigs. The young growth is thick; we think Jonathan said it had rolls of fat! The leaves sit on cushions and have a tufted appearance, but come straight out of the trunk in some places. The thorns are usually short, straight and stout but, if longer, they may have a slight curve. Height is up to 6 m. The flowers are white pompoms scattered along older growth, while the pods are sickle-shaped, narrow and dehiscent with fine grey hairs.

The last species we looked at was Acacia robusta (splendid acacia). Just to muddle you, this has some two or three subspecies so distinct they should be separate species. Here we were face to face with subsp. robusta. This is a higher altitude ROBUST species with large very deep green leaves of distinct shape and pointing upward. Branches grow out horizontally and the thorns are up to 8 cm in length; once out of the browse zone these are much shorter or lost. There are no hairs whatsoever and it looks as if it had been pumped up with hormones or fertilizer! Flowers are in white balls, while the dehiscent pods are straight or slightly curved. It reaches 8 m in height.

The rain held off so the main body of our troops unmurmuring marched for miles to the river for minimum reward – there were some splendid birds, a few warthogs and a fascinating cobra skin.

This writer couldn’t help wondering what the basic purpose of acacias is in the general bush ecology and why they are such efficient survivors. There are over 1300 species in the genus of which over 900 occur in Australia. As to its economic value you’d almost gather that gum Arabic is the principal factor. This comes from Acacia senegal, mostly found in the Sudan but spread right across Africa presumably to Senegal at the continent’s western point. The gum for sweets comes traditionally from Acacia senegal, but Jonathan says Acacia karroo forms a perfectly good substitute. Acacia bark is a source of tannin. Timber…well yes. Best is Australian Blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon). I have a beautiful desk in England made of Tasmanian Blackwood; I guess it’s closely related.

The day held a last puzzle for us. We found a fearsome bush whose thorns were in fact spines (please could someone define the difference) which was very late in coming into leaf. It almost had the pundits stumped and certainly was no Acacia. The final consensus was Rhus pyroides.

My thanks to Jean Whiley for lending me her estimable notes.

-Eric McNair

TSINDI RUINS, MARONDERA: 16 JANUARY 2000

Approximately 30 people gathered in the car park of the Tsindi (formerly known as the Lekkerwater Ruins) in the Marondera district. After a talk by Rob Burrett about the culture of the people who had built the ruins, we set off.

The hill has two peaks with the ruins on the northern one. The altitude is quite high (1660 m at the northern summit). I imagine that the rainfall is also relatively high and we saw many species typical of wetter, high altitude places. After a reasonable, if rather late, rainy season, the vegetation looked magnificent, especially the herbaceous vegetation.

The other main influence on the flora at Tsindi is of course that it is rocky and we were generally on rocky slopes, walking on thin soils over rocks or, especially near the summit, amongst large rocky boulders.

Hymenodictyon floribundum. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

A characteristic tree of rocky hills which we saw frequently was Hymenodictyon floribundum the Firebush. Although not in flower, we found some of the old flower spikes, with their pair of conspicuous long petiolate paddle-like bracts at the base.

Brachystegia glaucescens, the Mountain acacia, was very common and the typical grass of rocky places, Danthoniopsis pruinosa. Tetradenia riparia, the Ginger bush, although not always in rocky places, was common here.

We stopped at one point and compared Vangueria infausta and Vangueriopsis lanciflora. These two species are indeed closely related (both belong to tribe Vanguerieae in the family Rubiaceae). Separating them is an old Tree Society chestnut, and although generally not too difficult, I still find on occasions difficulty in deciding. The phrase “Vangueria is hairier”‘ gives the main character, namely that the upper surface of the leaves of Vangueriopsis tend to become less hairy with a shiny dark green appearance. Comparing the two here, another good character appeared to be the brownish powdery bark on the branchlets of Vangueriopsis which was not present in Vangueria infausta.

Another characteristic species of rocky places is Maytenus undata, the Koko tree. The usual slightly unpleasant smell of the leaves was discussed and a number of suggestions made; like Kim’s idea that it smells like old kitchen shelf paper. Seen frequently were the green rope-like stems of Adenia gummifera, a common and sometimes very large liana in the savannah woodland.

Other species which are not confined to rocky places but which often occur there include: Cussonia natalensis, Garcinia buchananii, and Vitex payos.

Two spectacular flowering plants caught our eye. One was a sprawling yellow-flowered herb with leaves in threes. This was Sphedamnocarpus angolensis. This belongs to the family Malpighiaceae, most of which have hairs which are attached to the leaf in the middle and therefore have two arms. These are known as medifixed or sometimes malpighiaceous hairs.

Nearby was a striking purple-flowered Ipomoea with greyish-white leaves. I am afraid that the name I gave at the time was wrong; it was actually Ipomoea verbascoidea. Like other Ipomoea, it was producing milky juice. This is a common species, which also catches the eye in fruit with its very long silky hairs on the seeds.

At the summit, we climbed amongst the large boulders with their humus-filled crevices and a distinctly different flora was found. The main target of the day was Solanecio mannii, the Canary-creeper tree. This is a composite and, as is rare in that family, is a shrub, sometimes becoming a small tree. Although not flowering on this occasion, it has dense panicles of yellow flowers. A distinctive feature is the leaves crowded at the ends of the branches and below these are prominent and persistent leaf scars. It is commonest in the eastern districts but occurs along the watershed in rocky places in high rainfall areas.

Nearby was the shrubby species Erythrococca trichogyne, the Twin red- has simple alternate leaves and can be rather anonymous in appearance. Here it was in fruit. It has 2-lobed fruit; each lobe contains 1 seed which is enclosed within an orange aril.

A considerable colony of Diospyros natalensis was seen; this is a rocky species par excellence. Also Celtis africana, Rhus leptodictya and another high rainfall species, Grewia stolzii, which has white flowers and 4-lobed bristly-hairy fruits.

In the shady humus-filled, crevices we came across a fruiting Scadoxus multiflorus (formerly Haemanthus multiflorus), the Fireball. This generally flowers before the leaves, but here the leaves were well developed. They have a false stem which was strongly purple-spotted. Also seen here was a stinging nettle, Girardinia diversifolia. Zimbabwe, fortunately, is poorly served with stinging nettles; this is an annual generally hiding away in shady crevices. Also among the rocks was the sprawling Phytolacca dodecandra; this has fleshy alternate leaves and white flowers; it is typical of rocky hills. A distinctive climber, often seen in rocky places, is Cryptolepis cryptolepioides. It is, for example, very common at Domboshawa. It belongs to the Asclepiadaceae and produces milk and has paired fruits. Its leaves show a remarkable variation from linear to almost circular.

Two other Interesting species seen at the top were Schrebera alata, which has opposite compound leaves with the distinctive winged rhachis. Plants with a winged rhachis are very few and this feature makes this species easy to name. In flower was Olinia vanguerioides. This, again, often occurs in high rainfall areas in rocky places (Domboshawa again springs to mind). It has opposite leaves and looks a bit like a Rubiaceae (this is implied by the specific name – like a Vangueria) but it lacks stipules and often has a red petiole and leaf base.

After lunch, we climbed up through rather thicker miombo woodland to the summit of the southern kopjie. At the top, Maureen spotted two epiphytic orchids on a small Parinari and these were promptly identified by Werner. One was a succulent species with “terete” (i.e. almost circular in section) leaves which used to be helpfully known as Tridactyle teretifolia but is now called Tridactyle tridentata. Growing with it was Polystachya greatrexii, which has small pseudo-bulbs. It is named after a Mr. Greatrex who collected extensively near Harare. The species is in fact described from a specimen from Domboshawa.

All in all, a very enjoyable day; the rain held off, the shortage of fuel did not deter people and both the plants and the habitat were excellent.

-Mark Hyde

CHRISTON BANK: 22 JANUARY 2000

It is not often that we write up the walk on the fourth Saturday of each month, but Saturday’s walk had some plants of exceptional Interest.

Our walk took us from the car park down through miombo woodland of various types to the Mazowe River at the bottom; this is actually at an altitude of c.1260 m. Our goal was to find the species of Teclea (Rutaceae) which grows there, mainly because I had not seen it before. The going was not easy in places, but the lush riverine vegetation was well worth the effort.

The Teclea was easy to find; there is quite a bit of it and it grows in the shady riverine forest at the top of the stream banks above the river. It has glabrous, ever¬green 3-foliolate leaves which have pellucid glands, pale greyish branchlets and bright red fruits. It is Teclea rogersii, which is what was expected and indeed, according to Bob Drummond, it is well known from there.

Acokanthera oppositifolia. Photo: Rob Burrett. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

In the riverine vegetation were enormous trees of the Wild olive, Olea europaea subsp. africana. The understorey had Acokanthera oppositifolia, with striking purplish berries, leaves of the orchid Eulophia streptopetala, the Stem-fruit, Englerophytum magalismontanum and a rather unusual climber Solanecio angulatus. The latter is of course in the same genus as the Canary creeper tree we saw at the top of the Tsindi ruins; it looks quite different however, as it has greyish leaves which have few deep lobes. Another somewhat unusual species seen is Osyridicarpos schimperianus; this is related to Osyris but is a weak climber. It is common in the eastern districts, for example forest edges in the Vumba, but it is quite unusual in the Harare area.

An interesting crop of aliens was also found. Apart from Passiflora subpeltata which is quite common in the northern parts of Harare, we also saw Passiflora edulis, which outside the eastern districts I think is not common. Climbing high into the trees and bearing its long fruits was the Cat’s-claw creeper, Macfadyena unguiscati; this is also well naturalised close to Harare but this site shows how it can spread. Another abundant species was Cardiospermum grandiflorum festooning the trees and bearing its inflated fruits. In the understorey was Senna septemtrionalis, bearing yellow flowers and black pods.

Walking back though the woodland we came across a plant of Thunbergia crispa. This is the plant with large deep purple flowers which we saw at the edge of the riverine vegetation at Calgary farm last year. In fact, the area is quite like Calgary and also the Holloways place in Welston Rd, neither of which are very far from Christon Bank.

Christon Bank is a very rich place botanically and as an indication of this, I covered 4 pages with plant names, probably more than at the Tsindi ruins.

-Mark Hyde

NOTES FROM THE LAY-BYS

Umsenya

I was very pleased to see an old friend still alive – but only just – at the Redwood Road signpost 52.5km out of Bulawayo on the road to Victoria Falls. Erythrophleum africanum, known in SiNdebele as umsenya or umbako, and in Shona as mushati, is sometimes called the ordeal tree because its bark contains the poisonous alkaloid, erythrophlein, which was used in times gone by for trials by ordeal. This particular specimen is the largest of its kind that I have seen – 23 m tall in June 1987, with a bole diameter a little more than 78 cm. In November 1987 it was struck by lightning, and in April 1988 it appeared to be completely dead. But when I saw it again at the end of August 1999 there were one or two live branches in full new leaf.

Joas dos Santos, a Dominican priest in Mozambique (1586-1595), described trials by ordeal in his ETHIOPIA ORIENTAL, which was published in 1609-They use three kinds of Oathes in Judgement most terrible, in accusations wanting just evidence. The third oath they call, Calano, which is a vessel of water made bitter with certaine herbs, which they put into it, whereof they give the accused to drinke, saying, that if he be innocent, he shall drinke it all off at one gulp without any stay, and cast it all up again at once without any harme: if guilty, he shall not be able to get downe one drop without gargling and choaking.

Umsenya is an associate of the dominant trees in the Kalahari-sand forests of north-western Zimbabwe, but I have also seen it on the deep sands of Gonarezhou National Park. Because of its mainly non-commercial sizes it has received little recognition as a timber tree, but Umsenya has a reddish brown wood that is hard, heavy, strong, and suitable for all the uses that have given the wood of Zambezi teak its great reputation.

-Lyn Mullin

A BRIEF VISIT TO JACANA LODGE 13 – 16 December 1999

Jacana Lodge is one of several in the Save Valley Conservancy, the largest wild life reserve in Africa, formerly a group of 21 ranches, now banded together to restore natural game such as elephant, rhino, buffalo, hippo, giraffe, kudu, etc, to be sustained by developing tourism in the area. Jacana Lodge has a scenic situation next to a wetland euphemistically termed a pan, said to be teeming with birds of all kinds – maybe, if only you could see through the welter of over¬grown reeds and grasses. The turn-off from the main (wide tar) road from Chiredzi to Sabi-Tanganda has a good gravel surface for about 40km through arid, open veld. The sight of 5 large fever trees Acacia xanthophloea told us we were near, but the next 5km along tracks through sugar fields, churned up by heavy vehicles was no joy. However, when we came to leave Jacana Lodge, we were guided along a new road through the mopane forest, so much better, and soon to be opened and signposted.

Our party of four, V, Do, M, and Du, was welcomed with a tray of cold drinks, much appreciated. During our 2+ day stay, we came to depend on the same smiling, competent and knowledgeable service from the manager and hostess, Albert and Georgina Paradzai, ably assisted by Stephen Midzi. Whatever we wanted, or asked about, whether game-viewing drives or queries about trees, animals or birds was quickly and courteously arranged or answered. Our accommodation was in spacious rondavels, comfortably furnished and well-screened, plus electric light and hot water. Wide stone paths avoided mud, as quite improbably it rained on the Monday of our arrival and on and off all day Tuesday. (We saw the Geminid meteorite showers under difficult conditions, amused at the counter-claims that these were only fireflies). The hanging pods of the Kigelia africana advised caution on taking a shortcut to the dining area – later we saw many more of these trees.

Colophospermum mopane filled the skyline across the wetland with its bright green foliage, yet around the Lodge itself, Acacia tortilis with its greyish-green leaves, whether as a thorny shrub or as a flat-top tree, dominated. Other acacias recognized were Acacia galpinii, Acacia nigrescens, Acacia nilotica, and the vivid Acacia karroo in full flower.

Our interests were not all exactly the same. Do hankered after seeing big game, and though we went on several rives he saw only impala and warthog. Both V and M were keen on their trees, and Albert was able to identify a wide variety for them, some found only in this area, such as the great Albizia glaberrima along the banks of the Save river Du was happy to be in the bush, and reveled in the larger trees, such as the Albizia, Khaya anthotheca, mopane at least 30 m high in one area, and of course the baobabs Adansonia digitata – one like a lady in overlapping pink crinoline skirts, and another with a thriving honey factory. We shared a common interest in birds, and frequently Albert would stop the truck, saying “I can hear such-and-such a bird” (which we never did) “let us see if we can spot, it in that tree over there”, and usually we then did. Around the lodge, the call of Burchell’s Coucal was heard frequently, a liquid du-du-du-du-du-; and one high for Du was to see two of them perched in a tortilis tree with their wings spread out fan-wise, drying them after rain.

We went down to the Save river on two occasions, once on a rainy morning and again for a cloudless sundown the next day The river was in flood, about 400m across and just as much sand banks. We saw many waders, but also a tawny eagle taking its time drinking at the water’s edge; and best of all, a flight of white-faced whistling ducks in V-formation low over the water, both when going downstream and then returning.

Besides the trees already mentioned, we saw many Dichrostachys cinerea, Combretum apiculatum and Combretum erythrophyllum growing alongside each other, unusually large Combretum imberbe or Leadwood trees. A large Lonchocarpus capassa or rain tree, Spirostachys africana (Tamboti) and Cleistanthus schlechteri (false Tamboti), Sclerocarya birrea, the Marula, and a tree with pear-shaped woody fruit, Schrebera trichoclada. Albert’s tree knowledge included knowing how the various leaves and bark were used medicinally by the local people, e.g. the Euclea divinorum, the diamond-leaved Euclea, edible fruit (not tasty) but used as a strong purgative. Many shrubs can be identified by the smell of their crushed leaves, the Zanthoxylum capense, or small knobwood, being an obvious example with a strong smell of citrus oil.

So much to be seen, learned, and enjoyed, but too short a time. Coming back to Harare, via Tanganda and Mutare, and seeing large areas of the Save Valley almost devoid of trees or bushes made us realise just how beautiful the Jacana Lodge portion of the Save Valley Conservancy is. Its lush vegetation, either exclusively mopane or else mainly acacia, depending on soil type, interspersed with occasional pans or dams, home to knob-nosed and whistling ducks, and Spur-winged geese. All in all, a visit to be remembered with much pleasure.

-Duncan Torrence.

THE CORAL TREES OF NEW CAPE

The farms Weltevrede, Lombardsrust, and Johannesrust were pegged. Then the others moved to Thoms Hope where the rest pegged their farms… through their perseverance, they opened up the new area of North Melsetter, and thus the whole of Gazaland – dream of Moodie, Jameson, and Rhodes – was occupied as British Territory.

S. P. OLIVIER (1957) – MANY TREKS MADE RHODESIA

For more than 45 years, from about 1908, the main access to Melsetter (now Chimanimani) from Mutare was through Cashel and along the 70-odd kilometres of dirt road that often became a nightmare during Zimbabwe’s main rainy season. Much of this road travelled through a farming area that had been settled in 1896 by members of the Henry-Steyn Trek, which had set out from the Kroonstad district of the Orange Free State in May 1895. The trekkers, led by John Henry and Johannes G.F. Steyn, numbered 15 families and four single men, for a total of 34 adults and 62 children. Seven of the families (14 adults and 23 children) were named Steyn, and they pegged so many of the farms on either side of the Tandaai River that the area was at one time dubbed “the dirty tablecloth”.

One of those farms was named New Cape, and was included in an acquisition by the Forestry Commission of more than 17 000 hectares of land in the Cashel district in the early 1980s. And in the grounds of the old homestead of New Cape are two exceptionally large specimens of the common coral tree, Erythrina lysistemon, also known as the lucky-bean tree, a species of the high-altitude woodlands, and usually no more than 10 metres tall and up to 70 cm in stem diameter. The Shona names are mutsodzo or musinzana, and the fact that there are only two of them is a reflection of the species’ relatively limited distribution in Zimbabwe.

The coral tree is well known for its beautiful scarlet flowers, which appear from July to October, usually before the trees come into new leaf. The standard petal is long and narrow, enclosing the other petals and the stamens, and the flower spike almost has the appearance of an elaborate and colourful epaulette. Also well known are the striking red-and-black seeds – the “lucky beans” – which are borne in cylindrical and sharply constricted black pods. The coral tree is much more widespread in South Africa, and it features in local folklore and medicine, but it is also a popular ornamental tree that can be grown very easily from truncheons.

The two trees at New Cape might possibly have been planted, but their exceptional diameters make this unlikely. In January 1988 both were 14.4 metres tall and the larger had a bole diameter at breast height of 1.5 metres and a crown spread of 15 metres. The smaller of the two could not be measured satisfactorily at breast height, but its diameter at ground level was 1.16 metres and its crown spread 18 metres. Trees of this size would be a magnificent asset in a large garden not only for their own beauty but also for the attraction they have for sunbirds, red-winged starling, and other nectar-loving birds.

-Lyn Mullin

ANDY MACNAUGHT CHARMAN