TREE LIFE

October 1999

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday 5 October. Botanic Garden Walk at 4.45 for 5 p.m. We will meet Tom in the car park and continue with the Euphorbiaceae family. There will be a guard for the cars.

Sunday 17 October. A return visit to Mwenge Dam in the Glendale area should be of interest. From a Tree Life of 1988 we are told that the vegetation below the dam wall is well preserved with good sized Antidesma venosum, (Tassel Berry) and Afzelia quanzensis (Pod Mahogany) as well as the not so often encountered Ekebergia capensis.

Saturday 23 October. Mark will be away so the walk is cancelled.

Tuesday 2 November. Botanic Garden Walk.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Sunday 10 October. Please note the second Sunday of the month when we will go to Huntsman Farm at Turk Mine (Williams family) to look at some plantations of indigenous tree species and a nursery, as well as the bush on the farm. Promises to be an interesting trip. Meet at Girls’ College car park (Pauling Road entrance) at 8.15 for 8.30 sharp departure.

MATABELELAND BRANCH OUTING, 4th July 1999

“The sedge has wither’d from the lake And no birds sing.”

It is certain that when John Keats penned these lines, he did not have in mind the Matabeleland Branch of the Tree Society. However, it is a most apt description of the circumstances pertaining to our visit on the 4th July, 1999, to the Mtshabezi Dam. This structure is one of the area’s latest and largest, and a sizeable body of water has now built up behind the impressive wall.

There was much discussion and consultation of maps as to the best way to approach, and we sped down the Jo’burg Road as far as the Umzingwane River, where we turned off on the road signposted to several small local villages.

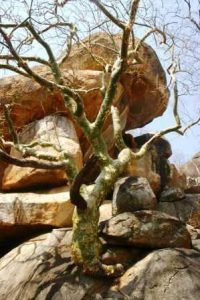

As we proceeded the sky darkened and guti settled on the windscreens of the three cars that transported us. The scenery became grander as we drove into the Matobo Hills. It was gratifying to observe how the imposing granite domes were still very well clothed with enormous trees.

Commiphora marlothii. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Once again, we were returning to the land of peeling Paper-bark Trees. Both Commiphora marlothii and Albizia tanganyicensis were present. At first, the dominant Euphorbia was Euphorbia ingens, but as we dropped in altitude Euphorbia cooperi var. cooperi appeared, and the forests on the hills became dominated by the graceful, elegant outlines of the Mountain Acacia, Brachystegia glaucescens. On the valley floor there were great stands of Mnondo, Julbernardia globiflora. Many of them still bore their seed pods above the canopies. There were quite a few trees that suggested that these two genera had hybridized.

The large blue letters of a signpost proclaimed that we had reached our destination, and everyone set off immediately to climb the steep kopjie to view the lake.

The silence was eerie. Only the distant “clump” of a wielded axe was audible. It wasn’t that I saw no birds. In the trees below the dam wall was a small flock of Red-billed Hoopoes. But that was all, and these usually very noisy birds uttered no sound.

I reached a point on the hillside where the lake was now visible. I sat down to enjoy the view. The Mountain Acacias were largely leafless and I could see a “finger” rock that protruded from the forest on the opposite bank.

The climb stimulated appetite and we were able to find some concrete slabs on the lee side of the granite boulders, where we were sheltered from the bitter wind. Here we partook of lunch. The clouds parted, allowing the sun to warm us.

Then we drove off round the back of the kopjie in search of a spillway. Here was a delightful clump of hybrid aloes, resplendent in their blooms. On the way we had seen plenty of Aloe aculeata and Aloe chabaudii, the bright red and yellow and pink panicles illuminating the gathering gloom on the hillsides. This clump was Aloe excelsa X Aloe aculeata. Several Aloe greatheadii also thrust their pale, sickly greyish-pink inflorescences into the scene. Among the aloes the silence was again oppressive.

In a previous issue of Tree Life, somebody lamented the lack of seed on trees this year and attributed it to the excessively heavy rains. I suggest that the rains “tra-la”, in the words of W.S. Gilbert, “have nothing to do with the case.” It is the lack of bees that has caused a pollination crisis, seemingly nationwide. I am informed, authoritatively of some disease that is decimating our hives. It is not the moth, but something else.

Joy Ketts tells me that the hives she used to have on her Hillside property were moved to the Citrus Estates at Mazowe, where they were desperately needed. Add to this our predilection for honey and often wasteful methods of gathering it, and the problem is compounded.

Here in the Matobo Hills there was certainly some sort of pollinator. A few Aloe greatheadii had set seed that was still green and immature. But there were no bees or sunbirds round the other aloes.

A fence barred further progress, but a stile afforded access to the lake by foot. While I waited for the party to return, I discovered a strangler fig. It had done for its host, which could be identified no longer. Jonathan suggested it was Ficus salicifolia (Ficus cordata). Certainly the leaves were slender, tapering and lanceolate. They were a tender, clear shade of green.

It is this particular variety of fig that is the huge and famous Wonderboom near Pretoria, its spreading, lax branches have drooped down. Where they have touched the ground they have rooted and new trees have grown. This has resulted in huge, complex trees covering a vast area. Apparently this remarkable system of natural layering is not typical of this species.

Higher up, the kopjie boasted a fine forest of Euphorbia cooperi, var. cooperi. All the trees were yet teenagers. From their branches, I was able to calculate that they were between ten and fifteen years of age.

Besides the aloes, bright red splashes of colour were provided by Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia, wearing their spring foliage. These trees were saplings also, and I didn’t see any that could be called mature.

For me, the highlight of the outing was quite definitely the unexpected occurrence of some large Baobab trees, Adansonia digitata. Imperturbable, inscrutable, and quite naked, they dwarfed some very large Mountain Acacias.

The road home retraced former forays into the enchanting Brachystegia glaucescens woods that adorn the Old Gwanda Road. There were, quite suddenly, sprawling masses of Euphorbia griseola, and odd specimens of Afzelia quanzensis, the Pod Mahogany, their characteristic seed pods, still green, hanging among fresh, verdant foliage. There were also Marula, Sclerocarya birrea.

It was an excellent outing and we thank Jonathan for his expertise and tutelage.

-NORMA HUGHES.

VUMBA: THURSDAY 12 AUGUST 1999

Eight members of the Society combined Heroes’ Days with the following weekend and visited the Vumba. We stayed in a house called Shumba Rock, which is situated a few kilometres down the Essex Rd and is managed by the Vermeulens from Culemborg, where we stayed in 1989. The house is raised somewhat giving a view over a valley and to the NW the Lion Rock range from the side. Apart from the bitter cold at night we were all very comfortable. My younger son was especially delighted to find a working video machine and a supply of tapes.

As always the three days in the Vumba produced much interesting information that was new to me.

The first day, Thursday, was a local day. It was distinctly chilly and most people started the day in woolly jumpers, only to cast these off later in the more sheltered forest. The party split in two with the more intrepid group (Andy, Werner and Linda) going up towards the Lion Rock range and the other (Maureen, Rose and me) walking more gently down to the Essex Rd and from there exploring the Freshwater Rd.

Shumba Rock was formerly known as Cherry Trees and one of the main features of the forest surrounding the house was numerous large specimens of Prunus cerasoides, the Himalayan Flowering Cherry. I had no idea that this was so well naturalised in the Vumba forests; it does of course grow well along watercourses around Harare. It has striking bark with horizontal stripes, and shiny pieces of bark peeling off, so that the trunk appears shaggy. On the petiole are glands and the leaves do not smell of almonds when crushed as the native Prunus africana does. In the flowering season which I gather is short-lived, it has pink flowers.

The forest was notable for the False Fig, Trilepisium madagascariense. How often we have been confused by this species in the past, but the milky latex, the very dark green leaves and the characteristic short acuminate apex serve to identify it. In the understorey were specimens of Dracaena fragrans. This plant is usually unbranched with very dark green leaves arranged around the central stem. Another Vumba species with milky latex we saw was Sapium ellipticum. This belongs to the Euphorbiaceae and has noticeably serrate leaf margins.

A number of alien species had successfully invaded the forest. One was a tall ginger with broad alternate leaves; at the apex of each stem was a large spike, now fruiting with orange fruits. I used to think that these were a species of Aframomum (a native genus in the Zingiberaceae, a species of which we were to see the next day at Ardroy) but Aframomum spp. have inflorescences which arise laterally from the base of the plant or the rhizomes. Matching this in the herbarium, it was a good match with Hedychium gardnerianum. This is a successful escape from gardens in other moist warm parts of Africa (e.g. S Africa and Mauritius). If this identification is correct, the plant will have yellow flowers with reddish exserted stamens. Perhaps any readers who live in the Vumba would like to watch out for this. The same plants were seen two years ago in the Cloudlands area of the Vumba.

As well as this exotic, the forest also had a large, possibly planted Loquat (Eriobotrya japonica), some specimens of Cestrum aurantiacum and lemon (Citrus limon) trees.

Another enormously successful invader is the Silver-leaf (Desmodium uncinatum). We are very used to seeing this around Harare, but it was frequent in the Vumba too.

Several times we were confused by a rather anonymous-looking tree with alternate simple leaves; however, the slightly grey underside gave it away – it was an Avocado Pear (Persea americana).

Strychnos lucens. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

A remarkable woody climber we saw frequently throughout our visit was Strychnos lucens. Its typical Strychnos-like leaves are 3-veined from the base, very dark green and glossy and the plant bears striking paired tendrils. Another glossy climber was a species of Landolphia, which was very common in the trees. The leaves are milky, a characteristic of the family (Apocynaceae) and the fruits spherical, about the size of a very large golf ball.

Also frequent in the forest was the climbing Canary Creeper (Senecio tamoides) with its yellow bunches of flowers. Another climber seen was Behnia reticulata. It is a monocotyledon with broad leaves and interconnecting lateral veins between the main veins. In this forest, it was in fruit with spherical white fruits 2 cm in diameter.

On the roadside banks of the Essex Rd a yellow-flowered composite, Hypochaeris radicata, was common, its stems arising from a rosette of basal leaves. It is one of the tribe Lactuceae with milky latex. This is a European species that is now well naturalised in the E Highlands and occurs typically on roadsides.

Down the Freshwater Rd, the road crosses a stream and there we came across a small tree with alternate simple leaves. This was Casearia battiscombei. When held up to the light the leaf lamina may be seen to have translucent streaks. The species belongs to the Flacourtiaceae. Nearby were the beautiful purple flowers of the Pride of Manicaland, Polygala virgata.

Further on, a remarkable find was a small shrub in the forest understorey ‘with prickly leaves in whorls of four. This was an escaped Macadamia. We also saw it growing as a planted plant.

Other spp. seen were typical of the Vumba: Aphloia theiformis, Bridelia micrantha, Carissa bispinosa subsp. zambesiensis, Choristylis rhamnoides, Cussonia spicata, Erythroxylum emarginatum, Halleria lucida, Keetia gueinzii, Podocarpus latifolius, Polyscias fulva, Rauvolfia caffra, Teclea nobilis, Toddalia asiatica with its fruits like tiny naartjies, Trimeria grandifolia and Vangueria apiculata.

In the afternoon, we drove up through an orchard to a further piece of forest. This was not so full of cherries and other exotics and we saw some additional species we hadn’t seen earlier: Myrianthus holstii (the leaves of which Coates Palgrave says fall with an audible plop), the Soccer Ball Tree, Tabernaemontana stapfiana and Piper capense with its swollen joints. A small slightly fleshy herb on the forest floor might be Leidesia procumbens, a herbaceous Euphorbiaceae, but this needs to be checked.

All in all, a very successful first full day in the Vumba.

-Mark Hyde

“TAKKIE’S FOREST” – Friday 13 August

Regrettably, Takkie Bannerman was away but instructions were left so that the magnificent chunk of Vumba forest was ours to explore. It must be marvellous to have this a stone’s throw from the front door.

One of the hazards of Tree trips over weekends is that the second evening tends to be a bit more festive and the after effects cause cloudy vision the next morning. So here we were on the edge of the forest with an exotic worth mentioning with 3-veined glossy green leaves, opposite and decussate. Simple – says my muddled brain it’s a Strychnos! Some discreet comments followed and Mark kindly pointed it out as a Cinnamon tree – Cinnamon verum, the crush and sniff test of the leaves confirmed an aromatic odour. This large tree with a substantial bole must be quite old (perhaps Takkie may know the age) and is certainly majestic.

The species noted as we wandered into the cool gloom of the forest were much the same as the previous day’s sightings and included the climbing Strychnos lucens (correct this time) with magnificent tendrils and the nondescript Tarenna pavettoides. Being forest, the need for thick corky bark is minimised, so as a result almost all those worth mentioning have only a smooth grey bark, which is not a reliable identifier especially when the leaves are sky high.

Polyscias fulva. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Luckily the dominant trees forming the canopy are Polyscias fulva, which, if we remember Tom Muller’s suggestion, to look for the particular (curious) branching pattern, Albizia gummifera almost leafless and the triangular-shaped leaves of Macaranga capensis. The largest of all the trees are the magnificent Newtonia buchananii, these providing the preferred habit for many of the epiphytic orchid species, which as Werner pointed out, survive the dry periods from the moisture provided by the early morning mist rising from rivers and streams.

Some other details worth noting: Carissa bispinosa – we’ve often mistaken it for the more common Carissa edulis but here the spine is much more delicate with the length of the forked spines being just 1-2 cm long. Surrounding the clearing in the forest clumps of Brillantaisia sp. with lilac flowers light up the almost uniform green understorey. Here, Takkie propagates Tree Ferns – some of these being [the Australian] Cyathea cooperi, which appear to be reasonably quick growing as most of these magnificent plants were of a good size – it was so pleasant here with the sun filtering through I could have stayed all morning! Anyway enough dreaming and back to the trees with a typically Eastern Districts Fig – Ficus craterostoma – with well-defined truncation of the leaves, Syzygium cordatum with a label denoting the vernacular name as ‘Mukute’.

Albizia adianthifolia noted as ‘Mujerenje’ and found by accident, a thicket of ~@*!%* Smilax anceps – fiendish in a forest as the hooks are small and inconspicuous and takes the place of Acacia ataxacantha in the Eastern Districts!

With encroaching agriculture, the forest fringe is narrow, blending into what is for us more easily recognised woodland with Cussonia spicata, Pittosporum viridiflorum and Garcinia buchananii. The GPS, belonging to the Hydes and also referred as TOY by the technophobe’s, provided a quick and easy altitude reading of 1165 meters once we were out of the tree cover.

Further along the Essex road and after a quick stop at the dairy to replenish supplies Mozambique was only a few tantalizing km away and closer to the ill-defined border the road cuts through an area of decomposing granites and shallow soils which are friable with nasty signs of erosion appearing regularly. The woodland on this ridge is characterised by stunted Uapaca kirkiana – large leaves and little else, whereas in the fiat areas around the streams, thickets of Guava and a number of Avocado pear (Lauraceae) mask a well-worn path that is evidently a back route into Mozambique – we learnt later there is a police post nearby for this reason. Despite being a relatively low altitude of 990 m the area is also moist, as evidenced by the numerous colonies of lichens and epiphytic orchids hanging in the main from the two species of Brachystegia, namely Brachystegia spiciformis and Brachystegia utilis; the latter is easily distinguished as it looks like Mufuti – Brachystegia boehmii with a greater number of leaflets but of smaller size. Apart from the common species we see on the highveld, this attractive area had a few surprises such as Zimbabwe creeper – Podranea brycei with a few remaining pink tubular flowers, the climber Clematis sp. festooned in the riverine strip and masking what seemed to be Sapium ellipticum and a new one for me being Uapaca sansibarica.

On the slow walk up to where the vehicle was parked we came across Werner leaning at a strange angle over his tripod and camera focused on a large nest in the fork of a long expired Msasa. This appeared to be inhabited by wasps and was left alone!

The rest of the party suffering from the inevitable arboreal overload walked some distance along the road leading into the Burma Valley and its plantations of banana’s, banana’s and more banana’s! Stopping by a small stream Maureen pointed out an Erythrophleum suaveolens, unfortunately rather hacked about, probably the actions of the road crew and not those desiring its potent properties as it is an ‘ordeal tree’ in traditional medicine. This lush spot also had Raphia palms and more epiphytic orchids, but as we walked along the stream it became noticeable that the banana plantations recently established were only about 5 meters from the stream bank. With these friable soils the high potential for erosion surely a few more meters of vegetated river bank wouldn’t harm the bank balance?

Our thanks to Takkie for making arrangements and to the Hydes for providing transport.

A. MacNaughtan

SATURDAY 14TH AUGUST

This morning, we set off down the Essex Road. The first event of the day was an abortive drive down the Cascades Rd. The name had suggested a lovely vision of waterfalls and their attendant interesting plants but reality was a long dull drive through wattle and gum plantations until eventually we came out on the Essex Rd again. We therefore retraced our steps and parked nearly opposite the Cascades Rd turnoff.

This was quite interesting forest with more false fig and naturalised coffee plants in the understorey. A short walk down the Essex Rd gave us a climbing composite with yellowish flowers, Microglossa pyrifolia and in a stream the striking purple inflorescences of Brillantaisia ulugurica [Brillantaisia cicatricosa].

However, a little hidden path into the forest hugging a stream took us to what was in my view the most exciting discovery of the weekend, namely the Excelsior Falls. The path slowly climbs, the stream becomes steeper and the water “whiter” until finally you reach a little man-made pool above which tumble the Falls. We have visited the Vumba for many years and did not know of them – they seem to be a well-kept secret.

Thalictrum rhynchocarpum. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

In this moist mossy shade amongst tall Acanthaceae we found Vernonia wollastonii, a climbing species, Thalictrum rhynchocarpum, the leaves of which look like the fern genus Adiantum and a small herb, the Wild Sanicle, Sanicula europaea [Sanicula elata]. Finally, we returned and stopped for lunch. Close by was another Casearia, clearly a more widespread species in the Vumba than we had thought.

The afternoon was spent walking down (and sometimes up) the Essex Rd until we reached “Myrianthus corner”. The altitude is lowish, between 1100 and 1200 m and an interesting if rather dusty flora was in evidence. It was very warm, particularly by contrast with the nippy temperatures of Shumba Rock and some members of the party took the opportunity to doze off in the forest.

Most striking was the climber Gouania longispicata, which as the name suggests has long spikes of yellowish flowers. It is very common in the Vumba. There was also Thunbergia alata, (Black-eyed Susan); this is sometimes seen around Harare as a garden plant, it has the unusual feature of a winged petiole.

Xymalos monospora is another common Vumba species with its thickly textured leaves which vary in shape and extent of serration. This belongs to a little-known family the Monimiaceae. The Zimbabwe Creeper, Podranea brycei, scrambled in the forest edges, mingling with the abundant Microglossa.

A very interesting three days in which a lot of the interest is to be found in the species we could not identify. For example, near “Myrianthus corner” was a tall, striking yellow Senecio, new to me and a prostrate Lobelia, which again I had never seen before.

Sunday 15th August, we packed up to leave. Just after breakfast, we were unexpectedly visited by Darrel Plowes and his wife. Darrel had brought several boxes of marvellous botanical books for us to look at, many of which would be very useful in one’s botanical library!

The drive back was non-botanical apart from the lunch stop in a small copse a few hundred metres off the main road just on the Harare side of Headlands. Although it had been badly hacked about the area was surprisingly rich and included Acokanthera and Sericanthe andongensis.

-Mark Hyde

MUCH MORE THAN A FIELD GUIDE

Jonathan Timberlake, Christopher Fagg, and Richard Barnes, with illustrations by Rosemary Wise. A FIELD GUIDE TO THE ACACIAS OF ZIMBABWE. CBC Publishing, Harare. 160 pp., 23.7 x 15.4 cm paperback. Retail price ZW$430 (approx.).

For an introduction to this review of the keenly awaited field guide to the Zimbabwean acacias we cannot do better than quote from the authors’ preface on the inside front cover of the book –

‘For many people concerned with land management, whether agriculturists, wildlife managers or interested naturalists, the species of Acacia (thorn trees, muunga or mukaya) found over much of Zimbabwe are a typical component of the bush, but can pose great problems in terms of identification. Some of the species can indicate soil type and land potential; some are of significant economic value in themselves for browse or fencing, whilst others have great potential for improvement of degraded lands or for various products such as gums. To date there has been no readily available and usable guide to the acacias of the country and much of the information on the 40 species found in Zimbabwe is scattered and inaccessible to the layman.

This book on the Acacias of Zimbabwe sets out to provide the interested person with a practical field guide to all the species found here and to provide information on their distribution, ecology and uses. It is hoped that it will not only give those managing the land and natural resources, in whatever way, greater insight into their task, but also encourage a greater understanding and knowledge among the interested public on this fascinating group of trees and shrubs. Finally, it is hoped that it will stimulate further research so that we understand better the role that these species play in the environment’.

The authors’ aims and objectives in producing this book should be realized to an extent that they probably have not anticipated. It is much more than just a field guide. In its 160 pages it sums up practically everything known about the Zimbabwean acacias, and it could justifiably be classed as one of the best publications ever to have come out of Zimbabwe – certainly the best of its kind.

The introduction to the book provides a concise account of the taxonomy and classification of the genus Acacia, including two boxes giving a synopsis of the historical classification systems, and one box summarizing the present classification of Zimbabwean acacias. The introduction also deals with the origin and distribution of acacias, and their ecology and distribution – all of this in only 7 pages.

Then follows a description of the acacias as trees (or shrubs); a note on how to use the field guide; a dichotomous key to acacia species (which the reviewer has not yet tested); a note on collecting acacia specimens (including advice on how to avoid the common experience of having all the leaves fall off in the press!); and a very useful acacia character matrix in tabular form, spread over two pages.

The main part of the book (pages 24-139) is taken up with brief monographs of the 44 species and subspecies that occur in Zimbabwe, including Faidherbia albida (formerly Acacia albida). These are arranged in alphabetical order of species, each of which is dealt with under the headings Description, Field characters, Distribution and ecology, and Notes. The last two headings are packed full of interesting and useful information, and go well beyond what one would normally find in a field guide. The illustrations by Rosemary Wise of each species and subspecies are of exceptional quality. Readers will notice that in some of the distribution maps the species may be depicted as lining the main arterial roads of the country; this is because many of the specimens housed in the National Herbarium were collected along the main roads, and it means that a great deal more exploration and serious collecting needs to be done to provide a complete picture of each species’ actual distribution.

Within the main part of the test are 16 numbered boxes dealing with a range of general topics pertaining to African acacias. These boxes are filled with information that would not normally be available to lay people, and provide the book with a very valuable “extra”.

The final sections of the book deal with some of the exotic acacias growing in Zimbabwe; illustrations of the pods of acacias with globose inflorescences, and those with spicate inflorescences; lists of indigenous acacias by area and by habitat; an illustrated glossary; references; lists of common and vernacular names, and synonyms; and, on the inside back cover, an acacia species matrix in tabular form – this matrix, together with the character matrix and the dichotomous key, should provide the interested person with all the help needed to identify any particular species; But beware the hybrid!

The glossy, paperback cover contains excellent, eye-catching photographs by Richard Barnes, and makes the presentation of the book very attractive. At retail price of around $430 this book is a very good buy and the 23.7 x 15.4 cm format makes it an easy one to carry around in the bush.

Lyn Mullin

For a number of years, the production of Neem tree seedlings has been successfully undertaken by Binga Trees Trust.

Dr Warndorff the Programme Director of the Trust writes … “some of the trees that we have grown from seed 2 years ago are now 3 metres high. Apparently Binga is a good climate for this tree.”

However, Neem seed is a difficult item to come by; this year Forestry in Harare has not been able to supply us with any seed as their source of Zimbabwean trees did not carry any seed at all. We have, however, still some seedlings from last year and also some trees grown from cuttings. Any person interested in buying Neem trees can contact us in Binga: Tel. /fax 015-321 or P O Box 82, Binga. About once a month we come to either Harare or Bulawayo and we would be willing to deliver at a suitable central place.

7th BOTANIC GARDEN WALK, September 1999

As a very small group we were treated to Tom’s concentrated attention as we continued our study of some of species in the Euphorbiaceae family.

But the first distraction was the magnificent display of orange flowers of Fernandoa. The flowers are large and colourful – deep orange and yellow with a good supply of nectar for the bats that do the job of pollination. Do members of this family all flower early i.e. Rhigozum sp. seen on this walk, Jacaranda, Tabebuia, – (the one-day wonder from the Caribbean with brilliant yellow flowers seen in many gardens), Spathodea, and Kigelia?

Tom mentioned that Fernandoa produces good mulch and the slash is interesting with lilac striations.

The first of the Euphorbiaceae family which we looked at was the genera Bridelia. Bridelia atroviridis, found only in the Haroni/Lusitu forest, has heavy dark green foliage with strongly marked veins and berries which are black when ripe. This species is usually a small tree.

A bigger species is Bridelia mollis found on kopjies in the higher rainfall areas.

Bridelia cathartica is divided into two subsp. – the common one which we easily recognise is Bridelia cathartica subsp. melanthesoides, the second is subsp. cathartica, a creeper rather like Phyllanthus reticulatus which occurs along the rivers in the lowveld.

Croton pseudopulchellus. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Croton pseudopulchellus is a small shrub with very small but typical Croton leaves, i.e. with silver undersides very liberally sprinkled with orange gland dots. This small shrub, usually found on Kalahari sand was at its best in the gardens, covered in small white flowers.

We looked at Androstachys johnsonii, the fascinating ironwoods that provide the title of a famous book set in the lowveld. They occur on the windward slopes where the moisture they require is provided in the form of mist. The simple leaves are round, thick, dark shiny green on the top surface, and white and woolly on the under-surface. In the past, this woolliness has caused clogging problems in heavy machinery used in bush clearing.

Tom told us of interesting evergreen circles, ± 200 metres across, that can be seen from the air over Gonarezhou. These occur in the fine Triassic sands. The evergreen components in these Brachystegia circles are mainly Suregada procera and Suregada zanzibariensis. Once again obtaining their moisture from winter mist.

Spirostachys africana (Tamboti) seems to have many of the Euphorbia features, milky latex, fruit with three lobes resembling that of Margaritaria, and like the crotons, the leaves turn red in autumn. Tom told us that it is difficult to find viable seed because the fruit is always parasitised. Strange, really, when we consider that Euphorbia species are supposed to be poisonous!

The succulent Euphorbia we looked at were Euphorbia fortissima from the Zambezi Valley with oblong sections as compared to Euphorbia cooperi, whose branch sections are triangular. Euphorbia confinalis typically has a thick trunk with a small head of branches and occurs in the Sabi valley and Bikita area, Euphorbia lividiflora is rare and occurs in the southeast of Zimbabwe, and of course Euphorbia ingens, the Candelabra Tree, well known and common over most of the country.

We will continue next month with this large family which is represented in most parts of the country. We thank Tom for a very interesting and entertaining walk as usual.

Maureen Silva Jones

The Kazungula Tree

‘The gateway to North-Western Rhodesia is at Victoria Falls, across the great bridge which crosses the gorge at nearly 40 feet higher than the cross on St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. In earlier days it was necessary to cross the Zambezi by a ford at Kazungula, higher up the river. This place is named after a large native tree, the Muzungula, growing at this spot, and under which there is a camping-place. This tree is known to Europeans as the “Sausage Tree” owing to its elongated seedpod resembling a sausage.

H.C. DANN (1940) – THE ROMANCE OF THE POSTS OF RHODESIA

It is not uncommon for a place to be named after a tree, but it must be unique for three places in three countries to be named after one and the same individual tree. This sausage tree, known to the Lozi people as muzungula, and to science as Kigelia africana, stands on the southern bank of the Zambezi River about 77 kilometres upstream of the Victoria Falls at the confluence of the Zambezi and the Chobe, and very close to the point where four countries – Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia (Caprivi Strip) – meet in the river.

The tree is actually in Botswana, perhaps 50 metres from the Zimbabwean border. David Livingstone is said to have spent a night under it in November 1855, en route to his historic rendezvous with the Falls, and it subsequently became a campsite for one of the few practicable crossing places on the Zambezi before the great steel bridge was completed in 1905. In 1987 a ferry still plied between Zambia and Botswana at the old crossing place (perhaps it does to this day), and the south bank landing was only a few metres from the tree.

Quite how the story of Livingstone’s association with the tree gained currency is not known to me, for he didn’t mention it in his writings, but there was a plaque claiming that this tree was Livingstone’s historic camping site. If it really was, Livingstone would not have recognized what was left of the tree in October 1987. What was the main bole had been reduced to a 2.7-metre-high stump, hollow and burnt out, with no more than a shell of outer wood still standing. The rest of the trunk and the main branches of the crown had broken away some years before – no one could say when – and were lying beside the stump. I made some measurements of the remains but I was not allowed to photograph them – there was political tension in the area at the time because of a South African military position on an island close by. My reconstruction was of a tree about 16 metres tall, with a bole diameter (at breast height over bark) of about 1.3 metres, and a crown width of 16-20 metres. So, all in all, the Kazungula Tree must have been a fine specimen in its day.

But it was not dead when I saw it. A short, thick, sucker stem, 46 cm in diameter, had grown up alongside the original bole, and although it contained a lot of dead wood, it was still producing shoots and foliage at the end of 1987, more than 130 years after Livingstone had passed that way.

This tree has given its name to the village of Kazungula across the river in Zambia, to the Zimbabwean border post, and to a tiny settlement on the Botswana side of the border on the road to the ferry landing. Although it took root in what is now Botswana, many of the tree’s historical associations are with Zimbabwe – but there is no proof that David Livingstone really did camp under it on his way down the Zambezi to the Victoria Falls.

-Lyn Mullin

ANDY MACNAUGHTAN CHAIRMAN