TREE LIFE

J A N U A R Y 1993

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday 5th January: Botanic Garden walk at 1645 hours for 1700 hours. Park at the Herbarium where we will meet Tom Muller.

Sunday 17th January. A patch of unexplored bush very close to Harare seems a sensible venue for this time of year. Mr. David Berger is our host and we’ll meet him at the farm at 1000 hours. Mr Steven Mavi from the herbarium hopes to be able to join us. One of his interests being the use of various parts of plants for medicine etc, we look forward to an interesting walk.

Saturday 23rd January at 1500 hours. Phone Mark Hyde to confirm the venue for his walk at this very interesting time of year.

Tuesday 2nd February. Botanic Garden Walk.

April 8 — 12th Easter in Nyanga. Most places have already been reserved. Phone Mr . Ian McCausland in Bulawayo or Maureen Silva-Jones in Harare for further details.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Friday 1st January: Our usual New Year’s Day bash. Clem Von Vliet has very kindly agreed to open her home to us for our usual Bring and Share lunch. Afterwards if we have enough energy we can do some suburban treeing.

Monday 11th January. Urban Trails. Meet at Hillside Dams at 1645 hours for 1700 hours.

Sunday 7th February. Quiet-Waters. An all day outing. Rendezvous at the Ascot car park for an 8.30 departure.

Monday 8th February. Urban Trails

BOTANIC GARDEN ; TUESDAY 1ST DECEMBER, 1992

And the subject was FICUS

Initially we proposed looking at Combretum but we found all were leafless. We first examined F.exasperata and F.capreifolia, these also were completely bare reflecting their drought resistant character, brought about by their riverrine sandbank habitat. In addition to leaf fall we also found die-back on the woody growth, indicating what drastic self preservation measures, adopted plants can carry out to stave off fatal effects of drought stress.

From a similar riverine, if less sandy home ground, by contrast, F.verruculosa was in full leaf and fruit. Growing in close proximity we found both our local high veld representative and the taller Okovango type.

Two Zambian figs were discussed: a young plant only about chest height, bearing light and dark green mottled fruit, looking distinctly “KERMIT” like. This was F.ottonifolia sub.sp. macrosyce, found along the upper Zambezi in rocky gorges and riverine forest.

Systematically, this plant is close to F.sansabarica which some of us know from Murahwa’s Hill in Mutare.

The second Zambian fig was F.cyathistipula, a mature tree whose habitat is quoted as riverine or swamp forest, often on rocks or river banks, with relatively large fruit, with a thick spongy wall, which allows it to float.”

This species is close to F.scassellatii (F.kirkii), an eastern districts forest species which I have not met up with in the wild.

Another “first” for me was F.chirindensis, (with the best will in the world, it is difficult to refrain entirely from becoming the plant person equivalent of an ornithological twitcher).

Appropriately named, the type specimen was collected by Goldsmith in Chirinda Forest, the range of the species extends northwards to Zaire and Kenya in sub- montane mixed evergreen forest. A large handsome tree, it is also close to F.sansabarica. in Berg’s subsection Caulocarpea. We also looked at some of the more close to home, members of the genus, and the considerable variability displayed by F.natalensis and F.thonningii. I was interested to hear M: Thom Muller mention the formerly famous Presbyterian fig, which used to stand at the comer of what was then Jameson and Kingswey (new arrivals work it out). This was F.ingens, and there is history here. It must have been a pre 1890 tree and it was still in its prime when it was felled in 1979. Maybe with justification, I mean if would not be not be right for trees to go around pushing over places of worship, would it? The good news is that we know where some of its children are growing, safe and well.

Thank you Thom, for your usual informative and entertaining evening walk.

LONE STAR RANCH REVISITED : NOVEMBER 1992

In August 1985 the Tree Society visited the Lone Star Ranch and at that time Phil made some very interesting comments, one of which was that “Lone Star, at least the portion which we visited, is geologically remarkable.” So it is – but the geology is not all that is remarkable about Lone Star. The ‘portion’ referred to is an outcrop of Triassic Karoo sand stone and siltstones which form a. scenic ridge of rocks and trees and housing a proliferation of Bushman paintings. On our last visit we walked across the dam wall with the water lapping almost to the top was clear and fresh; today almost the whole of the 70 foot wall is visible and the water is muddy brown. Happily the lake is still deep enough to succour the ten hippo brought in from Gona re Zhou National Park and provides water for a host of animals and birds. On a beach laid bare by the shrinking lake, hay, horse cubes and cabbages are places for the hippo to feed at night: the baboons spend their days foraging and squabbling around the food, together with Egyptian geese and others. That is the feeding pattern taking place not only at lone Star but at Gona Re Zhou as well, and it is saddening and yet gladdening to go out into the Park to watch the animals that feed at the strategic feeding places where water is pumped into pans or tanks. A not easily forgotten sight is over 200 buffalo held in the central pens, plus a lesser number of other species in smaller pens and piles of hay, molasses, horse cubes and greens being off-loaded from tractors and trucks. An extract from a. pamphlet handed to us at Kwali Camp gives a better idea of the scale of this operation: “….. we are distributing +-/200 bales of imported veld hay per day, for the general species, plus concentrates and greens for selective feeders like Rhino, Klipspringer. Nyala and Hyrax. At our holding pens, we are taking care of +- 500 head of game that have been brought in from Gona Be Zhou National Park. These animals will be pen fed until the park is back in good shape and then returned.”

We hear that Mr Sparrow and others spend long hours in the workshops repairing pumps, and here it is confirmed by this extract…..”In Gono Re Zhou National Park we are distributing imported veld hay, and commissioning old, unused boreholes, in remote areas, where there is plenty of natural feed hitherto unused because of lack of water.” So it is more than just remarkable that people like the Sparrow family who saw the desperate plight of these animals and instigated a rescue that will last well into the New Year until the country has had a chance to recover from the drought.

On our first visit to the dam site the trucks were parked in the shade of some gigantic Brachystegia glaucescens– at the foot of the wall and it is in this area that yet another remarkable change has come about for here Kwali camp has been built by the Sparrow famiiy (father, son and daughter). Neat wooden twin-bebedded chalets nestle amongst rocks and trees, interspersed with lush green lawns and exotic plants (bananas, wild ginger, palms, aloes, succulents, etc. to create a cool tropical setting very happily enjoyed by numerous butterflies and birds. A wide stone path winds up around the steep incline to the top of the ridge where the dining area and the office are, this is a bit too steep in parts for easy walking and a hand-rail would help, but Edie Sparrow was unhappy about this as it is not in keeping with the setting. In this hot dry area dining under the stars is just the thing and so the tables are placed in the gardens under the trees and there is the added advantage of being able to see the life of the lake, of which there is plenty at any time of day. More chalets are being built and perhaps a pool, but always in close harmony with the natural setting of trees and rocks: maybe some day this will be an ecological education centre, but for now it is there for us enjoy and savour. Cresta Hotels have joined with Sandstone to under take the catering at both the more luxurious Induna lodge and Kwali Camp and hence the name “Cresta Sandstone”. Early mornings and late evening are the best times for viewing the game and the birds , but the vast variety of trees are there all day to be examined, admired and marvelled at.

-Vida de V Siebert

It was a very enjoyable trip down memory lane for Doug, Vida and I so when Vida asked me if I would pen a few lines for Tree Life along with hers, how could I refuse… ‘I do recall that I had not long been a member of the Tree Society when we visited Lone Star Ranch in 1985 and arboreal indigestion was to plague me a lot on that trip. I confess that this time I was much more relaxed and as I have also acquired the birding habit since then, I have become a little less intense about trees . The long journey down was pleasantly spent chatting and quietly watching the passing landscape, identifying those trees we knew. Once past Gutu we found a shady lay-by in which to have a refreshment break and try as we might the name of the large shady tree dominating the scene eluded us, although of course we did know it. It wasn’t until we got to our destination that we tracked it down with the aid of our Coates Palgrave — Dyopspyros mespiliformis (Ebony).

As we travelled on we kept seeing another old friend we felt sure we knew but, again, we were unable to put a name to it and it was not until we went on our first drive that our excellent guide, Tembo, told us what it was Acacia nigrescens – knobthorn. Tembo was to astound us time and again with his knowledge of both trees and birds – becoming very enthusiastic when we expressed more than average interest in both.

Acacia tortilis. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Another acacia – Acacia tortilis – (umbrella thorn) – was very much in evidence on our drives as was also the false marula – Lannes stuhlmannii – sporting its new green leaves and flowers at one and the same time. Strangely enough, we did not often come across the marula itself – Schlerocarya birrea – with its characteristic grey bark, flaking in patches.

Also seen frequently was Lonchocarpus capassa – the rain tree. In fact we were quite convinced on our evening drives, -once we had ruled out the fact that the wet splashes we felt on our skin from time to time were not rain, it was the L.capassa only to change it again in favour of the Cicadas (Christmas beetles)! And what a deafening noise these very large insects made – it seemed to be coming from almost pure stands of Colophospermum mopane.

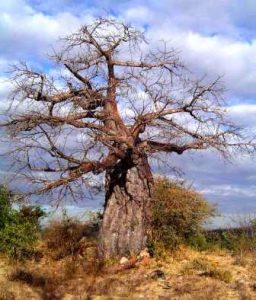

Adansonia digitata. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

On our way to some cave paintings we were discussing the size of a particularly large Adansonia digitata we had just passed and were told by Tembo that his rule of thumb for working out the age of the baobabs is for every 8 metres of girth you can estimate 1 500 years growth and this particular specimen was in excess of that .

I think it is worth mentioning that one morning we tried to have a walk below the dam wall but after an hour it became too hot and we had to give up. But not before we’d played hide and seek with a red-chested cuckoo who kept calling piet-my-vrou very loudly, giving his hiding place away and a purple -crested lourie revealing his beautiful colours and making his characteristic kek-ukek-kek sounds. It was quite a deep ravine and whilst down there we were able to examine a Ficus tettansis (rock splitter) with its roots positively flowing over the surface of a rock.

We were told that kwali is the Shona name for the Natal francolin which often scurried across our path on entering and leaving the camp. Right outside the chalets we couldn’t fail to recognise Combretum imberbe – (leadwood) and alongside that Combretum adenoganium. Beautiful tall Brachystegia glaucescens – (mountain acacia) with their slim, light grey trunks, stood like sentinels in the rocky kopjies behind us.

It was all so memorable. From the evening we saw the lions and a leopard (my first in the bush) and kori bustard striding off neck first in a terrible hurry, to the morning we left the land-rover in a dongo to go off in search of elephant. But not before we noted Sterculia rogersii looking so unlike the other Sterculia species we see. Androstachys johnsonii -(ironwood) and Spirostachys africana (Tamboti – African sandlewood) the wood of which makes beautiful furniture but sawdust from which can cause such terrible blindness.

The cackling of red-billed hoopoes contrasted strangely with the silence of the African hoopoes which were sighted whilst discussing Hyphaens natalensis grouped in various stages of growth, some barely off their knees and others so tall that they hardly looked like the same genus.

Whilst looking at a pair of tawny eagles Tembo pointed out some buffalo weavers’ nests which set us laughing over condominiums for birds. Playful long-tailed glossy starlings abounded but rarely seen were the beautiful plum-coloured starlings Also along the the way, we were fortunate in seeing white backed vultures and ground hornbills while, back at base enjoying meals above the lake, it was great to hear the cry of the fish eagles and see marabou, sacred ibis, and storks, both yellow- bllled and wooly-necked, as well as the Egyptian geese.

Congratulations to Cresta Sandstone for providing a great venue and a sincere thank- you to their staff for looking after us so ably. We look forward to an early return for more. Marjorie Barker.

THE LIMPOPO : APRIL 1992

Sentinel Ranch was the venue for this year’s joint expedition mounted by Falcon College and the Natural History Museum of Bulawayo. The latter fielded one of its most comprehensive teams in recent times by sending curators from herpetology, mamology, ornithology, palaentology and ichthyclogy as well as tecnicians from entomology, archaeology and National Monuments. I was asked to go along to do some botany and as a total amateur was greatly privileged to spend twelve wonderful days on the Limpopo with such luminaries as Kit Hussler, John Minshull, Don Broadley, Darlington Munyikwa and Fenton Cotterill.

Facts and figures frequently make tedious and mundane reading, but Sentinel’s vital statistics are hardly commonplace – they invariably fall into the superlative. The ranch covers about 20000 ha, enjoys almost 20 km river frontage on the Limpopo which is where the 500 m contour bisects the property and receives an average annual rainfall which is less than that in either Beit Bridge or Tuli Police Station. Fascinating things happen in this end of the wild kingdom simply because Sentinel is one of the largest, lowest and driest properties in the land. In this respect it is a unique piece of real estate.

In the 1940s Field Marshall Smuts envisaged the creation of a supra-national game park embracing substantial tracts of land along the Shashi and Limpopo Rivers in the Transvaal, Southern Rhodesia and Bechuanaland. It was to be called Dongola. Nationalist victory in the 1948 South African elections put paid to this and the Northern Transvaal lands designated for wild life were carved up instead for political patronage. So as the vision of a game park receded the Southen Rhodesia Goverment in the 1950’s divided its Crown lands west of Beit Bridge into three large ranches – Sentinel, Nottingham Estate and River Ranch. The former was bought by the Bristow family and made over to extensive ranching, although in the sixties and early seventies they also did interesting pioneering work in the domestication of eland. In 1980 a new generation of Bristows brought a complete change of direction. The cattle were taken off, the internal fencing came down and the land was given over to wildlife. Colin Bristow says it was the best decision they ever made.

The terrain of Sentinel falls into four broad categories, each determined either by its geology or its erosional history. In the south the Limpopo has cut a shallow dagger-shaped trough into sediments of the Samkota Formations. Away from the river the Homba Hills form a low rugged escarpment where dune bedded sand stones in pinks, creams and maroons have been sculpted by time into a landscape where the fanciful mind sees a ruined oriental temple-city and then with a change of light, the canyons and gulches of New Mexico and frontier America. Further inland the flood basalts of the Upper Karroo period masks these beautiful sandstones with a heavy and sombre cloak giving rise to an upland plain which extends northwards beyond the horizon to the ranch boundary twenty and more kilometres from the river. Colours, shapes, plants and animals and not least of all, the delight of the unexpected gives each place its specie ambience.

Lowveld rivers have a rare magic – blazing sands, shimmering ribbons of water, hostile spears of parragmites and the jungle-green cool of riparian forest are day-time images. At dusk comes the red cliche of an African sunset, cold beer and the scents of wood smoke and phyllanthus. Night rests the visual senses and sounds dominate – talk, laughter, fruit bats, hyena, Pells fishing owl and mosquitoes. And at dawn there is the smell of dew on leaf litter and the thrilling reveille of heuglin robin. Kipling’s river is no different from the rest only more famous because of the Elephant Child and it was there that we spent twelve blissful days in one of three reed cottages (each complete with shower, bath, basin and flush loo) that make up Colin Bristow’s safari camp on the Limpopo.

The big river draws one back daily, not simply because our dormitory and refectory sit on its banks, but because the central nave of the riverine forest, a natural wonder where size and simplicity dominate the architecture. refreshes both mind and soul. Ficus sycomorus (with leaves not quite ‘as scarberous as the books suggest especially on sapling growth), Schotia brachypetala, Acacia xanthophloea (Kipling’s fever tree) Xanthcercis zambesiaca, are the columns of the forest cathedral. We thought we might find Acacia albida too, we could certainly see it across the river but the Ana tree was only met with to both the north and south of the camp. Scandent Combrefum mosambicense and Acacia schweinfurthii festoon and drape branches from top most gallery to ground level. Phyllanthus reticulatus (the boiled potato well of summer evenings in the lowveld) competes more shyly with these rampant creepers (look at its “compound” leaf and see by the axiliary buds that things are indeed not compound at all). Grewia flavescens subsp (olukonde), Plumbago zeylahnica, Mayatenus heterophylla and Croton megalobotrys (it always reminds me, fruit excepted, of mulberry) ornament the lower and middle levels.

The riparian forest sits narrow and wedge-shaped in section, on a well drained levee. The land thereafter falls back into a slack area of impeded and deferred drainage. Tributary streams, because of the superior height of the levee, cannot form natural junctions with the mainstream and therefore deflect themselves to run parallel with the Big River. Soils are more silty and clayey (because in flood finer particles are carried and deposited further from the main stream than are the coarser sand particles) and water therefore sits more persistently on the surface here than elsewhere, be it after rain or flood. This is a zone of great difficulty for plants and only the most robust subjects can overcome the chemical and mechanical problems the soils present in this dambo area. No wonder they are for the most part rebarbative and enploy almost every fom of hook thorn, spine and prickle to fend off man and beast alike. Here we find Acacia tortillis (the shittim of Genesis armed with both hooks and spines). Acacia xanthophloea, Hyphaene petersiana (the Southern ilala palm) Ximenia americana, Maytenus heterophylla, the vicious Ziziphus mucronata, spines one up and one down. Lonchocarpus capassa comes unarmed but then itchithamuzi” has magic powers for self defence. Albizia anthelmintica is found on the fringes. It is poisonous, but only to tape worms as its specific tells us. There is a wonderful dambo about two kilometres from the western-most boundary. One comes to it suddenly on rounding a steep riverine bluff. The visual impact is arresting – an oval of short sedge, as vivid as a golf green, spiked with the sulphorus trunks of large Acacia xanthophloea sits in an amphitheatre of pink sandstone.

Away from the dambos, shallow sandy pediments rise towards the boulder slopes of the Homba Hills. Solenacea dominate the scene – Solonum kwebense (the cause of “maldronksiekte” – mad-drunk sickness in sheep and goats) and Lycium cinerium are everywhere in the understorey. Acacia tortillis so distinctive with its misty green umbrellas extends into this area from the dambos and one also finds Acacia senegal var rostrata, squat, obconical and so different from its lanky hilltop cousin Salvadora austra is also common. Gnarled and twisted with grey green foliage, it could at a distance pass for a Mediterranean olive. Boschia albitrunoa (tho shepherd’s bush) completes this biblical scene.

Tributary streams rising in the sandstone hills and in the basalts beyond, cut these sandy plains and nourish a riparian fringe which is rather different from the one along the Big River. Nyala berry, Croton megalobotrys, and ichitamuzi make an encore, but Maerua angolensis, Berchemia discolour, very occasionally Spirostachys Africana (tamboti) and Combretum imberbe are all new and give this ribbon of forest its distinctive and rather sombre character.

Commiphora pyracanthoides. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

The Plains end abruptly at the foot of short boulder strewn slopes. Here one enters the land of commiphora and grewia. We found the Commiphora edulis (rough leaf), commiphora, Commiphora mollis, Commiphora pyracanthoides, Commiphora tennuipetiolata (long delicate petioles and creamy white bark) and Commiphora africana, (woolly leaf). In the‘ middle and lower levels we saw Grewia bicolor with its finely serate margins and as soft as the best kid), Grewia flava (silver grey), the two varieties of flavescens (as abrasive as bicolor is soft) , Grewia retinervus, Grewia tennax (small leaves reminiscent of Lantana montevidensis) and Grewia villosa (very similar to Dombeya rotundifolus). But there were many other subjects too and the boulder slopes support the greatest diversity of trees and shrubs – baobab, Lannea schweinfurthii, Combretum prunoides, marula, Tarchonanthus trilobis and many more. Among re-entrants where summer cataracts flow, one finds pockets that could be transplants from the Matopos and which hold the Clerodendrums glabrum and myricoiides, Croton gratissiumus and Barleria albostellata.

Often these rocky slopes are topped with low sandstone cliffs into which the ages and the weather have chiselled crannies and caves that have given shelter to man and bats for millenia. The bats are still there but man has gone and only the paintings and grain bins tell us that his tenancy stretched from the stone age to very recent times. The massive sandstones and skeletal soils of this summital zone support an entirely new plant community. Rock figs are everywhere. Ficus abutifolia and tettensis are the most common and almost as abundant as Ficus corda subsp salicifolia. We also found a specimen of Ficus ingens. The two latter species can produce identification problems and the best solution to hand is in Kim Damstra.’s key. (l6a Basal veins distinctly branched and almost straight, not parallel to leaf margin… Ficus ingens. 16b Basal veins unbranched, usually curved and running parallel to the leaf margin… Ficus Cordata ssp salicifolia.) Don Broadley took us to a wonderful Ficus abutilifolia. that he had discovered close to the Tongani River. The central stem of the progenitor was surrounded within a radius of about two metres by twelve secondary trunks where adventitious roots originating in the branches had converted on reaching the ground, into stem tissue. More curtains of aerial roots, some hanging only millimetres from the ground showed that this metamorphosis and spreading was an ongoing process. One was reminded of Kipling and Banyan trees (Ficus benghalensis). Hexolobus manopetalus, Papea capensis, Stenganotaenia araliacea and Albizia brevifolia are common sights and the latter invariably shows elephant damage. The acacias are represented here by Acacia erubescens (not to be confused with A.fleckii, because erubescens is the one with _the long petiole, and long name and rachial glands) and Acacia senegal var leiorachis which always reminds one of the slender tree on the willow-pattern plate. Sesamathamnus lugardii is one of the marvels of the area. We found it in flower, indicative perhaps of late rains. The blooms are as fascinating as the tree itself, which looks like bonsaied baobab. The corolla is five-lobed cream or white and held on a narrow cinnamon coloured tube at least 6 cm long. This tube is attached laterally rather than terminally to the branch and beyond the pedicel there is a conspicuous spur 6 mm long, which to all intents and purposes looks like an extension of the corolla tube. One presumes it is a nectary which raises interesting thoughts on the physiology of pollination – perhaps a moth with a proboscus of at least 6 or more centimetres does it all. The blossom is sweetly scented – not unlike frangipani.

Craig Roberts, who was doing a Ph.D. on the klipspringers on Sentinel, volunteered to show us an “Adenium”. We eagerly accepted the offer and the prospect of adding the Sabi Star to our check list. We were certainly not prepared for what must surely be one of the most bizarre botanical sights in the land. There it was, perched on a low ridge – stout and barrel-shaped, with trailing vines sprouting from the top of the greenish keg. Leaves like a granadilla and tendrils modifying with age into threatening spines. Adenia spinosa and not Adeniun multiflora (my faulty hearing and not Craig’s pronunciation. We never did see one but were rewarded with an Qrbiopsis lugargii which John Minshull had seen on a previous expedition and took us to visit tfis time.

Basalt plains lie beyond the sandstone hills. Mopane thickets and scrub are common here, but this gives way in better drained regions to a parkland dominated by acacias, seasonal grasses and forbs. Large herds of wildebeest, zebra and eland roam the area as do kori bustards. A squadron of twelve took to the air when we ventured too close for their comfort. It was a breathtaking sight. Distance from base camp meant that we only penetrated this fascinating region once and although its woody species are rather limited it has a wealth of small plants which cry out for investigation.

Our wanderings in the twelve days yielded a total of over 100 species, 84 species in quarter degree square 2229 A2 and 74 in 2229 B1. The other disciplines were as well rewarded. John Minshull recorded two new species of fish for the Limpopo. Don Broadlcy found the barking geckos which had drawn him to the Limpopo in the first place. We sat late one afternoon on an island of Kalahari sand and were duly serenaded with the clicking-cum-chirping of the gecko chorus. Several specimens were collected and this for the first time ever in Zimbabwe. Nine palaentological sites were discovered and 181 bird species were recorded in one of the quarter degree squares. All too soon it was over and we headed for Bulawayo to dream of Kipling’s river and returning.

“But now, discharged, I fall away

To do with little things again…”

-Ian and Margaret McCausland

NYARUPINDA CATCHMENT Some December flowers.

The most exciting event recently was when Meg Coates Palgrave came to see Rothmannia fischeri growing amongst granite rocks on the southern boundary of the catchment on Gomo Estate which belongs to Mr Ian Barron. This ’find‘ by Mr Paul Zwanikken is note worthy for the Tree Atlas Project.

This woodland Rothmannia as distinct from the forest species, can tolerate drier conditions than the latter, but clearly this community of trees was not happy with less than average rainfall year after year, all had sparse foliage. Their crowning glory was large starlike flowers borne on the highest branches, a few had fallen, they were creamy white in colour and flecked with purple, their heavy perfume ressembled that of Gardenia sp. to which Rothnanmia is related, both are members of the family Rubiaceae.

Some branches bore shiny green fruit about the size of the small monkey orange (Strychncs innocua), some fruit had fallen, this prize was eagerly sought, there were three. Their skin was leathery and enclosed sticky seeds. Lingering, we pondered on the occurrence of Rothnannia here and came to the conclusion that in former times when the climate was wetter, this species was widespread in Brachystegia woodland, this relict community had survived along the drip-line of massive sheltering rocks.

It was re-assuring to see saplings of all ages, long live Rothmannia in Ayrshire District.

Ochna puberula. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

On a previous visit to the Rothnannia kopje we found an unusual species of Jasminun with a ruff of much-divided sepals much longer than the petals, a likely diagnostic feature. Nearby Ochna puberula’s yellow petals glowed in the shade beside a runnel descending the kopje, in a. similar watercourse there was evidence of human occupation – pieces of ‘flint‘, potsherds, hut dagga and half a bored stone. They chose to dwell in a natural amphitheatre, tall grasses have flourished in the arena, proof that the soil there is deep and moist, it may have been cultivated when the kopjes were inhabited by Iron Age people.

In the vicinity there are terminalias thought to be T. mollis which seen to be dying from numerous colonies of Loranthus/Tapinnanthes upon them. The semi-parasite’s requirments and the long dry seasons must havecontributed to their demise, they are sorry sight.

Tapinanthes’ flowers are specially adapted for pollination by nectar-feeding birds. This is the time of year to examine their flowers, five petals are joined at the base to form a tube which contains nectar. The flower buds open very gradually — the petals remain attached at the tips, when a bird inserts its beak between the petals to drink nectar, the flower opens suddenly and the pollen from stamens, which are attached to the petals, is forced on to the bird, the stigma of the next flower is dusted with pollen whilst the bird feeds.

There-is an excellent diagram of the undisturbed anthers of Tapinanthes in Marloth’s “Flora of South Africa”, where he stated that this pollination mechanism is unique.

In the field the tongue test for nectar has been disappointing, the birds cannot have supped from every flower… perhaps the nectaries are not active until later in the season, time will tell.

Civetries.

These have come alive with seedlings of Senna singueana, another legume-like seedling with a trifoliolate leaf, another whose first proper leaf is glossy and may develop a serrated margin. All three civetries contain remains of many kinds of Arthropods.

Mammalian residues, a characteristic of spoor in winter, rarely occur now. Small fig fruits have passed through only lightly squashed. It was rather a shock to find a length of bandage ravelled up with millipede ‘rings’ and heaven-knows what else.

That’s it for 1992, happy wanderings in 1993.

-Benidicta Graves.

GEORGE HALL CHAIRMAN