TREE LIFE

August 2020

MASHONALAND BRANCH

Trees – our heritage

There are again, no outings to report on, and as yet no upcoming events but I am hoping that those of you who do read Tree Life will find that this issue has much of interest.

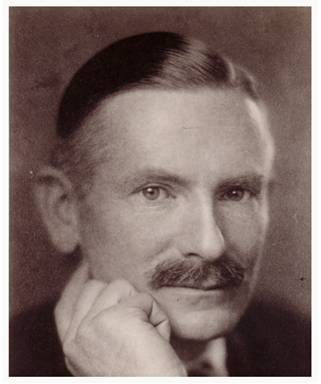

The lead article this month I have taken from the very excellent Online newspaper Daily Maverick and it is about the life work of one, Richard St. Barbe Baker. To quote from the article “He was not an ordinary man, this St Barbe, and his journey was not an ordinary journey. His goal was in the realm of fantasy: to protect the planet’s existing trees, to reforest the Sahara and to save Earth from environmental destruction. He took this goal very seriously.”

It is a fascinating read about a great man and a read that I am hoping will inspire many to start on such a journey. I have asked Clare Griffiths to write about the work she is doing on Rural reforestation, I think Clare’s work is one of a few such projects going on in our country at the moment. Meg has given us really interesting articles on Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration, a subject she has been pushing for many years and which we, who are lucky enough to have been to Catapu in Mozambique, have seen beautifully portrayed in Ant White’s programme. Then, we have a short, sad article from Ian Riddell with really depressing photographs of one of our favourite botanizing haunts, Henry Hallam Dam, which for so many years, in spite of being adjacent to the sprawling City of Chitungwiza, has been so well protected by the City of Harare authorities over the years. Something awful is happening here. Tree cutting is rampant – the people, the million or more people, who live in the surrounding area have no work, no money and it is a cold winter! The outcome is – look at the photographs Ian has supplied. These trees are cut at suitable axe height, maybe they will coppice, if we, as a Society bring this problem to the authorities and ask them to manage the woodland as they have done in the past. A prickly, no, a thorny subject which the highest authorities must act on and be responsible for – trees for all generations to come.

Keep well and safe.

Mary Lovemore

MERE MORTALS

Tree story: St Barbe and the Incredible Journey

By Don Pinnock• 23 June 2020

Every now and then history throws up an extraordinarily focused individual. One of those was a gentleman from Hampshire with a simple obsession with trees.

Once upon a time there was a man named Richard St Barbe Baker. He was not an ordinary man, this St Barbe, and his journey was not an ordinary journey. His goal was in the realm of fantasy: to protect the planet’s existing trees, to reforest the Sahara and to save Earth from environmental destruction. He took this goal very seriously.

He is no longer with us, and his story has become lost to all but a few who cherish his name. So I will tell a part of it here, particularly about his Incredible Journey. For he was a man way ahead of his time and should not be forgotten.

St Barbe was born in a country house in Hampshire, England, in 1889 and at some point, while wandering in the Hampshire forests, it came to him that he loved trees.

In the years that followed, trees had to make a bit of space in his heart for horses but were never displaced. As a teenager he went to study science at the University of Saskatchewan in Canada and spent a good deal of time thundering around on horseback with Amerindians.

Back in England he followed a loftier path for a while, studying divinity at Cambridge, but when the First World War broke out he signed up and went to France, winning a Military Cross instead. Back at Cambridge, having been injured and discharged, he studied forestry and – after graduating in 1920 – was posted to Kenya as a forester with the Colonial Service.

For a young country gentleman of the time his trajectory thus far was fairly normal. What followed was not.

He arrived in northern Kenya to find forests being decimated and the desert closing in.

“I was driven to the conclusion,” he wrote, “that it was essential to obtain the co-operation of the people to stem the tide of destruction.”

He discovered that the Kikuyu, when they cut down a portion of forest, left giant fig trees to collect the spirits of their felled companions. He also discovered that anything meaningful began with a dance. So he dispatched runners all over the country, inviting warriors to a dance of the tree spirits. Thousands came, all decked in war paint, and filed past his forest station, clan by clan.

What followed became the stuff of legend. He told them they needed to replace the trees they cut. They told him they thought planting trees was God’s business. He told them the spirit of the trees lived in the seeds and these could not make new forests without their help. There was, it seems, a collective “aha!” and, right there and then, Watu Wa Miti (Men of the Trees) was born. It was an organisation that required people (not only men) to protect and plant trees.

It caught on like wildfire. Within a year his Watu Wa Miti had nurtured and raised 80,000 trees. Then, under St Barbe’s guidance, the idea began to spread like the arms of an oak. At last count (and I am the victim of my sources here) the organisation had branches in eight countries and these had planted more than a billion trees. That is an achievement worthy of admiration, without doubt. This story, though, is not about tree planting but about the Incredible Journey undertaken in the name of trees.

St Barbe had seen the effects of desertification. In 1953, he decided the best way to fight the desert was to understand it. And to do that he needed to travel through the greatest one on earth, the Sahara.

It must be remembered that in the 1950s, the Sahara was pretty much still terra incognita to all but Taureg camel herders – a place where people ventured into and were never seen again. Travelling there was like going to Mars.

The start of the journey, St Barbe and his car (Image WikiCommons)

St Barbe plus two other Brits, in a vehicle that looked like a cross between a Model T Ford and a shoebox, planned to travel from Algiers (without French permission) across the Sahara to northern Nigeria, east though the Sahel, then southeast through the Congo, across the Ruwenzori Mountains to Uganda, then through Kenya to Mount Kilimanjaro. No radio, no backup plans. They left London with bags of peach pips donated by eager crowds in order to turn the desert into a Garden of Eden!

How to begin to tackle such a stupendous task, as to fight seven million square miles of desert? How could I, one man, reclaim the Sahara? It’s not even a project for one nation.

St Barbe listed their supplies as “cans of pineapple juice, soup powders, hard biscuits, fig preserve, lots of fresh citrus fruits, dry tablets of Horlicks malted milk and seven jerry cans of petrol given to us by the Shell Company.” Water was carried in goatskins. He wore a “Bombay bowler” which he soon lost and reverted to Arab headgear. He also lost his sunglasses.

St Barbe was nothing if not thorough. At the edge of the Sahara he felled a eucalyptus tree and counted every leaf. From this, he calculated the transpiration per leaf, then per tree, multiplied this by the number of possible trees per hectare and concluded that each day a hectare of these trees pumped 36 cubic metres of water into the atmosphere. No trees = no clouds = no rain = Sahara. Simple.

Before them lay a vast, barren landscape with not a tree in sight. They plunged into it. At the oasis of Djelfa they found goats nibbling the bushes. At Laghouat they found goats browsing up in trees. At In-Salah they found goats chewing at stumps. “They eat everything, trees, bushes, olives and tufts of grass,” St Barbe complained. He developed an abiding hatred for goats.

He chewed Horlicks tablets to stay awake at the wheel when they travelled at night, which they mostly did.

Old Arab camel-men told them stories of forests that had existed in the central Sahara in their lifetime; all cut for fodder and firewood.

They followed dry watercourses and St Barbe dreamed of drawing up underground water to raise millions of trees to push back the desert. At one point they traversed a thousand kilometres of desert without seeing an oasis or a person. They nearly lost their vehicle in quicksand. In the middle of all that they found a solitary thorn tree and nearly overturned in their excitement.

Heaven knows how, they got across the Sahara, rolled along the Sahel and plunged into the Congolese rainforests, marveling at their verdancy and aghast at the effects of slash-and-burn agriculture.

They climbed through the foothills of the Rwenzoris, barrelled through Uganda and into Kenya. In these two countries, they were shocked to see Sahara-like conditions advancing at speed. Finally they pulled up on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro.

Back in England, St Barbe sat down and puzzled through what he’d achieved.

“I wondered what to do,” he wrote in what was to become a book, Sahara Challenge. “How to begin to tackle such a stupendous task, as to fight seven million square miles of desert? How could I, one man, reclaim the Sahara? It’s not even a project for one nation.”

He began reasoning. The goats had to go. Then the oases had to be assisted to expand their tree cover and eventually link up, creating microclimates to stimulate rain. Then what about all those dry riverbeds? The water must have gone somewhere. Was it in vast, underground aquifers waiting to be tapped?

St Barbe’s Incredible Journey would be the rudder which set the course for the rest of his life.

“The Sahara affords a challenge not only to Africa alone, but to the world,” he wrote. “It offers a glorious opportunity to sink the political differences and past exploitations of our planet into a new creative economy, a new way of living, a biologically correct way of life bringing health and security.”

He worked tirelessly to get governments and organisations to work together to plant trees and halt the march of deserts. He befriended presidents and royalty, gaining their support for his projects. At his suggestion, Franklin D Roosevelt established a forest “shelter belt” from the Canadian border one thousand miles long and a hundred wide and formed the Civilian Conservation Corps which provided six million people with conservation work.

Tree planted by St Barbe Baker (Image WikiCommons)

He sat with peasants and warriors, urging them to sow seeds. He badgered the State of California into creating a forest reserve and he set up a Save the Redwoods Fund.

“The Ancients believed that the earth is a sentient being,” he wrote. “They believed that the film of growth around the earth is its protecting skin and that the earth feels the treatment afforded to it. Geological observation certainly points to this.”

In England, at the age of 74, he rode 530 km on horseback, giving talks about forests to schoolchildren. He took up flying lessons so he could see forests from the air. He wrote 20 books dealing mainly with trees. All are now out of print and virtually unobtainable.

In June 1982, St Barbe was in Canada to place in the Earth the last of the million trees he personally planted during his lifetime. It was a poplar. A few days later he died. His gravestone in Saskatoon reads:

Richard St Barbe Baker, OBE

9 October 1899 – 9 June 1982

Founder of Men of the Trees

Pioneer of desert reclamation through tree planting

Crusader of virgin forests worldwide

Since his death, two important discoveries have been made in the Sahara. As he had predicted, huge fossil aquifers have been found under the sands, one of them thought to be about the size of France.

The other discovery was the result of satellite studies by meteorologist Jules Charney. He found that green-covered areas absorb more solar radiation and therefore give off more heat. Warm air carries more moisture, which increases the likelihood of rain. Overgrazed or deforested areas are lighter in colour, absorb less radiation and therefore create cooler, less-moist conditions: potentially deserts. The conclusion is that deserts do not cause droughts, people do.

We now have much of the information needed to halt the spread of the Sahara. What we require, urgently, is the political will and a Richard St Barbe Baker – a man of the trees ahead of his time. If a new and better world emerges after Covid-19 in step with Greta Thunberg, his ideas would be a valuable blueprint.

DM/ ML

WOODLAND REGENERATION: Part one

I had the privilege of joining Greenpop, a tree planting initiative in Livingstone, Zambia for several years. Part of the initiation was to build a charcoal kiln close to the Lusaka road not far from Livingstone. This was interesting but ……. the hardwoods, Zambezi-teak, Baikiaea plurijuga and umtshibi or false-mopane, Guibourtia coleosperma were being felled with a chain saw and turned into charcoal.

Both species readily coppicing from their stumps. Photo Meg Coates Palgrave

However, the bright side was to see that both species were readily coppicing from their stumps.

About five or six trees were cut, as close as possible to where the kiln was to be built. Dragging logs is hard work, so the closer the better. On one occasion we found a stump already sprouting while the kiln was still in the construction stage, having been cut probably less than four weeks previously. The trees are cut more than 1 m above ground level, a convenient height for cutting, instead of being cut almost at ground level as happens when felled for the timber trade.

Many of the trees in indigenous woodland coppice readily and re-grow from a cut or broken stem or trunk. Coppice shoots can be produced anywhere along the stem or branches not just around the root collar. They appear to coppice more readily if they are cut at convenient axe height, rather than being cut close to the ground when only about 40 % of trees coppice and can take a couple of years before doing so.

Growth from coppice is fastest in the first two years but stems can reach a height of four to five metres in the 15 to 18 years. When re-sprouting or coppicing, the tree already has an established root system and it would make sense to manage the regrowth as a means of regeneration in the woodlands.

It seems to me if we cut a twentieth of the trees each year for 20 years in a woodland and managed the regrowth, like our cake, we could have our woodland and use it.

Left-hand arrow root-shoot; right-hand arrow coppice from stump Photo Meg Coates Palgrave

After the root-shoot become established as a small sapling the roots breaks away from the parent plant. There is a theory that the seeds of indigenous trees germinate and send down a taproot and then just sit for several years developing the root system underground before starting to grow above ground. Seed germination is often problematic. I suggest that the roots of apparent seedlings were actually root-shoots that had broken away and now growing on their own.

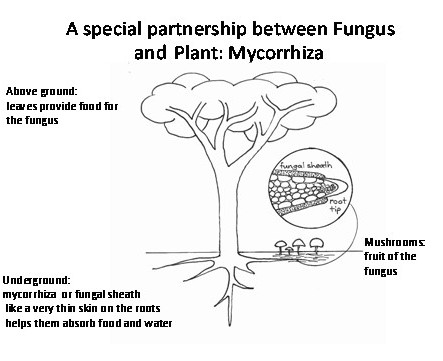

The advantage of regrowth from coppice or a root shoot is that the tree already has a root system so the roots all have the necessary fungus. Most of the soils in south-central Africa are poor in nutrients and so the trees have developed a symbiotic relationship with a fungus whereby the fungus assists in absorbing water and minerals underground and the tree provides the carbohydrates manufactured in the leaves from above ground. The fungus is probably somewhat host specific which is why some tree seedlings, particularly Musasa do not always survive.

-Meg Coates Palgrave

THE “MY TREES” OR “MITI YANGU” PROJECT, HURUNGWE

Right here, right now we are sitting in the Anthropocene – the sixth mass extinction to have taken place on our planet since it came into existence. A mass extinction is when over 75% of all species at that time become extinct. This has happened before, however what is new is that this is the first time that a species is responsible for this extinction. This extinction amounts to, at present the demise of 12 species per day. It is also the first time that a species has the ability to do something about this attrition. We know too that this window of opportunity is closing, and closing rapidly.

The causes of our current predicament are well known and include the usual suspects- overpopulation, habitat destruction, deforestation, climate change and the movement of species around the world. Solving this problem requires a multifaceted approach:- there is a plethora of people with different strengths, passions and abilities. Accepting that we all offer different components to a universal solution. People wishing to play a part need to embrace the component that they will be, and need to be that part authentically without creating a pedestal for that course of action above all others. No universal solution, no pedestals, just joint action towards moving in a common direction.

Zimbabwe is losing 10 million trees a year at present, an area the size of Wales every five years. We are surrounded by countries proffering similar figures. Insurmountable? Well, firstly we have no option to be defeated unless we see ourselves as the ones blowing out the candles. More importantly, signs of hope emerge from unexpected corners triumphant in their success in the face of impending doom such as a subsistence farmer in India, singlehanded planted a 550 hectare forest in his spare time over thirty years; India planted 60 million trees in a day last year, most of which have survived and China planted half a billion trees last year.

Plants themselves scream of their potential to succeed, given the opportunity to do so. This was why past extinctions were mentioned existence is a fought-for state. It is a struggle to have even got here, there are attributes of resilience in us species even existing. Conservatively speaking, an Acacia karroo tree will generate 100 000 seeds in a year and 98% of those will germinate if clipped, soaked and planted. The potential to turn our current predicament around is there. One hundred and two trees can generate 10 million offspring (I am not advocating putting offspring from 100 trees of one species, with the inherent limited genetic diversity into our ground, I am merely discussing here the concept of resilience).

This below is briefly the story of my last year in Hurungwe, north of Karoi, halfway to Makuti and then another hour off into the west where the rates of deforestation have been astounding, This is a place where we are building up a story of hope, a place where we are building a narrative of Zimbabwean reforestation, community owned, community driven, supported from outside, driven and powered from the inside.

This project, “My Trees” or “Miti Yangu” supported through Cicada Conservation and Zambezi Society.

Historically, I have been many things – large part scientist, large part artist, some part musician – a jack of some trades. I say this to illustrate that, like most of us, know quite a bit about some things, very little about others. Everyone reading this is similar. Like many of us too I have enthusiasm and the will to learn the how – to’s from people around me, communities around me (or Google). Never in the history of mankind have we been connected as we are now.

The task put before me was to find a way to set up in the first year a pilot of six nurseries, find 30 hectares and plant and steward trees.

Reforestation projects often fail. Analyses of failed reforestation drives suggest that there are four components in any such endeavour:- Financial capital (the money paying for it), physical capital (the space etc.), knowledge capital (knowing what to do) and human capital (peoples aspirations and wishes). It is almost always in the realm of investing in human capital that projects fail – they take time, they take investing in people, in relationship.

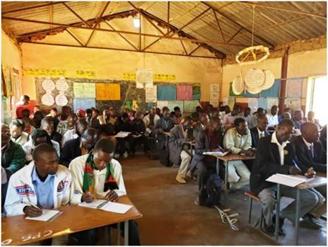

Discussions with the elders. Photo – Clare Griffiths

Last year, on being granted an MOU to work in Hurungwe I sat with headmen of ward 8, determined not to skimp on relationship -building. Asking the first question of the older people in the room “What was it like here when you were young?” set me on the most extraordinary serendipitous and humbling adventure. A lot of my previous ten years work in non-timber forest product work was more prescriptive, trickle down in endeavour rather than bottom up, more-empowering in its reach. What ensued was a six hour discussion about what used to be there, what was lost, how much more interesting food was then, and how much it pained the community to have lost so much. I barely spoke. Only enough to ask if we thought there was a way to regain it and how we could do this together. “Tinosimuka pamwe chete”= we stand up together.

Interestingly, it appeared that few people had thought we could grow indigenous trees – they were meant to grow themselves as they always had done. The community was adept at growing crops and exotic fruit trees but wanted our own Zimbabwean trees. People in Hurungwe do magnificent land preparation The little I knew now became necessary to add to the mix – some knowledge of soil, of methods of collecting, clipping seeds and what suits what soils – some science to add to the millennia of use and relationship with these trees.

My camp Photo Clare Griffith

A headman gave me space to camp indefinitely on his hill and there I moved and am still resident to this day. I love that every night his son passes through to see if all is alright and every morning ladies happen to walk by, the all import and questions about how I slept, how they awoke and our families. Then they would be on their way again.

These times are precious and often as we sat and talked of children, of baking bread and of what is difficult. Things like the the need for fuel-saving stoves emerged. This is important to address as 1 million of those trees we lose were used for cooking. If we could half fuel use nationally that in itself would save about 500 000 trees. Step by step we work on issues. I had built some before and so brought the bit I knew of technology into Hurungwe, where one member of the community builds, at present, 2 per day. If I take in two more PVC pipes used as moulds that number will double- I will take in ten. All moving so quickly.

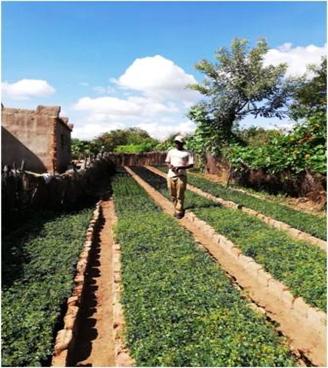

This is one of the nurseries he overseas now Photo – Clare Griffith.

I strongly believe that the only measure of ability is action. Most endeavours involve a pooling of information, drawing upon wisdom of others, fixing on a goal, whilst trying to fill in the gaps.

This man, was so excited that he built a nursery in which he germinated seeds and had 1000 saplings.. He now runs ten nurseries with 150 000 indigenous trees for reforestation in Ward 8. He is magnificent and I am humbled by Doubt Tagarapano, His work is meticulous, ten trees per row. This is one of the nurseries he overseas now

I am equally awed by View Chundu and Egnacious Chisuka and the teams they have built up to grow and steward trees once the seedlings are grown. Trees are only planted where the community has signed that they will steward and nurture these trees, not cutting any for 15 years, after when it has been decided in the community that we must have solved our fuel issue. We are working to address this, again, in a multifaceted way.

I am equally awed by View Chundu and Egnacious Chisuka and the teams they have built up to grow and steward trees once the seedlings are grown. Trees are only planted where the community has signed that they will steward and nurture these trees, not cutting any for 15 years, after when it has been decided in the community that we must have solved our fuel issue. We are working to address this, again, in a multifaceted way.

The enthusiasm to plant and grow and change the future narrative has yielding planting these trees in five different planting regimes, incorporating :-

Reforestation (which we do in areas where less than 10 percent of trees remain in an area, we plant around anything remaining, often with pioneer species right now as the ground is often degraded terribly;

Interplanting– trees will not regenerate if less than 20% of the original number remain – actually they can in an ideal world without communities still needing the wood for use. This is not the reality on the ground. All literature analysing this suggest that 20% is the cut off. The reality is that we, humans are adding more and more pressure so we need to take responsibility. In areas with less than 30% (giving ourselves leeway) our communities interplant indigenous trees.

Stewardship– areas that have more than 30% of trees remaining that the community would like to earmark for protection, the community undertakes coppice management as so well known by us through Meg Coates Palgrave’s coppicing powerpoint presentation;

Tree corridors– as promoted through The Acacia Handbook of Newton Spicer and Johnathan Timberlake (given to me by Tony Alegria- thank you Tony) have begun to be planted this year and over three hundred households are wishing to sign up this year. These corridors will help build a mosaic of trees rejoining woody areas allowing safe movement of some wildlife whilst pumping nitrogen back into the fields

Functional Woodlots– the communities have expressed a desire to have their own woodlots with the trees they would like in them – Muchachecha, mupondo, musanga. Mutowe amongst others – no gum – to give them fuel, food, forage and medicines. We are building up a supply of saplings at the moment together to meet this need, along with the stories and uses of these trees in a booklet. Much can be said of the tree species choices in those regimes

Suffice it to say that this year the planting of 40 hectares, not 30, was achieved and thus far 98% of trees have survived. Our nurseries will reach 20 in number next month. Trees are individually cared for by members of the community. Ward 8 has offered about 1000 hectare for this year’s planting, we intend to plant only 300 this year in the 2020/2021, trying to walk before running. and the nurseries are being extended to have sufficient stock for this.

Fuel efficient wood stove made from clay

Are we optimistic about this? Yes, for a number of reasons, primarily that it is a ground up community-driven enterprise, the problem and solution largely owned by ward 8 who dream of being the model for Zimbabwe’s indigenous reforestation project. Chief Chundu, is visionary in his desire to uplift those 13 600 families in his care and is vocal. Our team message has not prescriptively delivered to this community; we own the problem and the solution together and are trying to tackle it together. So far, all success – I am sure we will fall on this path as that is a critical component on the road to success but as my children say “Let’s keep our eye on the donut and not upon the hole”.

Additionally, as I stated at the outset, we are option-less, It is on our shoulders. People in these communities feel this even more keenly than we do. I have learned, living on my little hill so much of this last year: none of us want what’s happening; no one else can solve it, it’s up to us; we should assume that everyone we speak to knows something we don’t; we are stronger than we think we are and more empowered than we think. hat an exciting ride this will be.

Additionally, as I stated at the outset, we are option-less, It is on our shoulders. People in these communities feel this even more keenly than we do. I have learned, living on my little hill so much of this last year: none of us want what’s happening; no one else can solve it, it’s up to us; we should assume that everyone we speak to knows something we don’t; we are stronger than we think we are and more empowered than we think. hat an exciting ride this will be.

I end with a picture of three of my dearest visionary friends in Hurungwe.

We want to change the world – join us

The Sabhuku Tushera –View Chundu, Doubt Tagarapano, Myself and Egnacious Chisuka

-Clare Griffiths

And now we come to the sad story. I am grateful to Ian for drawing our attention to this woodland devastation so close to our city, and an area we, as a Tree Society group, have visited and enjoyed the botanizing many times. Likewise, this area was once a very favourite picnic spot for the folk around and about. Editor

GOODBYE TO HENRY HALLAM?

Henry Hallam, Prince Edward dam, Seke dam – call it what you will – is a woodland we have visited quite a few times through all its monikers and as recently as November 2019.

Evidence of de-forestation. Photo by Ian Riddell

I had occasion to cycle through there recently and was alarmed by the deforestation that is taking place. It is supposed to be ‘cared for’ by the City of Harare but they aren’t doing much of a job; truck tracks branch off every which way all along the road that runs through the woodland and stumps follow in their wake!

More evidence. Can this recover with careful Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration?? Photo – Ian Riddell

I should think that the woodland is going to disappear rapidly, to take on the appearance of the south side of the dam – scrub and rocks. Sad news indeed!

-I.C. Riddell. Email: gemsaf@mango.zw

CHAIRMAN – TONY ALEGRIA