TREE LIFE

May 2000

SUBS ($120) WERE DUE ON 1ST APRIL. PLEASE USE THE INVOICE ATTACHED TO THE APRIL ISSUE OF TREE LIFE.

WHILE THE PRESENT FUEL CRISIS AND OTHER PROBLEMS PERSIST PLEASE CHECK WITH ANY OF THE COMMITTEE MEMBERS TO ENSURE THAT THE SCHEDULED OUTINGS AND WALKS WILL ACTUALLY TAKE PLACE. THEIR PHONE NUMBERS ARE LISTED ON THE LAST PAGE OF THIS ISSUE.

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Saturday 6 May. Botanic Garden Walk at 10.45 for 11 a.m. The topic will be ‘plants on our field card but seldom seen’. We will meet Tom in the car park where there will be a guard for the cars.

Sunday 21 May. The Annual General Meeting of the Tree Society of Zimbabwe will be held on Sunday 21st May, 2000 at the lecture theatre next to the tea room in the Botanic Gardens, Fifth Street. Tea will be served at 9.30 a.m. followed by the A.G.M. After the meeting we will take a walk in the gardens. Please bring your chair, something to share in the way of eats and if you intend to stay a while, you may like to bring a picnic lunch as well.

Saturday 27 May. Mark’s walk will be at 2.30 p.m. at the property owned by Mr. Hatendi – Charmwood.

Saturday 3 June. Botanic Garden Walk.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Sunday 7 May. Visit to Helen and Wally Herbst’s Porter Farm in Nyamandhlovu to look at Sesamothamnus and Commiphora. Please phone one of the committee members for confirmation of this trip.

Chairman’s Annual Report 1999 – 2000

As the Tree Society year draws to a close and with it one of the most difficult periods the country has been through, I would like to take the opportunity to thank the farming community, who in spite of the enormous problems confronting them, still find the time to keep the society’s interests and objectives alive. The current economic situation has had an effect on the Society, inflation has made it such that our membership fees have had to increase substantially and the increase in the travel costs are in the main unavoidable, so it is gratifying that members find the resource’s to join up on our outings.

As always there are a number of individuals who give freely of their time and expertise and my thanks to them, namely Tom Muller for the Botanic Garden Walks and font of knowledge. Bob Drummond, Mark Hyde, our ever-present guru and Botanical guide, Lyn Mullin, for the many fascinating articles in Tree Life and wide knowledge of the country’s trees, Doug and Vida Siebert for collating and mailing Tree Life and Dickie Greaves for her regular contributions to Tree Life. We thank Maureen, who is secretary, editor of Tree Life and Tree mapping coordinator.

In Bulawayo, the committee is headed by Anthon Ellert, who together with Jonathan Timberlake, keeps the southern region alive and active and my thanks to them.

On to mundane business matters and following on from matters discussed at the last A.G.M. Firstly, the bulk of our finances have been reinvested in more lucrative sectors. The question of entry fees to the Botanic Garden has been discussed and the result is that free entry for the time being has been permitted for our monthly Botanic Garden walk. And my thanks to Miss Nobanda for making this possible as well as the free use of the lecture room for our Annual General Meeting. Further to suggestions raised at the 1999 A.G.M., various steps have been taken to increase membership with pleasing results. Enclosing application forms with the March issue of Tree Life has brought positive results and we welcome the new members and hope they can benefit from their membership of the Society. An entry has been included in the Thursday morning radio programme With Compliments and a limited response has come from this.

In addition, material has been placed in the Mukuvisi Woodlands bookshop. Membership has risen to 238 – the best for a couple of years which is most encouraging. My thanks to Jonathan Timberlake for allowing us to use his questionnaire, to which Bulawayo members responded earlier in the year. The results from the A.G.M. were published in Tree Life 234 of August 1999. From the responses, the respective committees now have better ideas as to what our members require from their membership.

Details of the year’s outings have been omitted as they are well documented in Tree Life and I would encourage you to refer back to these editions as there is a fount of information contained in the articles. One of the more important activities during the year was the introduction to the Protea Atlassing project, when a team from Kirstenbosch explained to some of our members how the system worked and the correct way to map the Zimbabwe species. The year’s outings have covered a wide spectrum of the floral kingdom, hopefully providing members with a mechanism for a greater knowledge of botany. In view of the present conditions we apologize for any upsets that may occur with the planned calendar but please bear with us during this period.

In conclusion, my thanks to you, the members, for our interest and support to the Tree Society.

Andy MacNaughtan

BULAWAYO BRANCH OUTING

The unremitting rains ceased temporarily and at least long enough for us to go to the Randell’s farm, just off the Victoria Falls road.

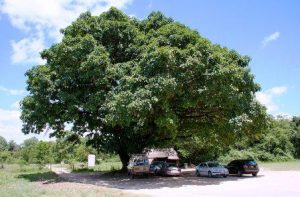

Acacia erioloba Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwea

Only 23 different species were noted, of which 6 were Acacia. Of these, Acacia erioloba was the most striking. These many trees were immense and impressive. They were absolutely festooned with golden orb spiders and their webs.

The lawn in front of the farmhouse had been planted with several exotic species, and two indigenous, one of which does not occur here naturally. This was a Fever Tree, Acacia xanthophloea. I am struck by how well the Fever Tree adapts itself to and flourishes in habitats other than its own. There was a whole planted grove of them on the farm at Turk Mine, and I know of at least one in Harare, and another in Bulawayo. The Randells informed us that all these planted trees were established more or less at the same time, a few years ago, but they were vastly different in size, according to their wonts. Chorisia speciosa [Ceiba speciosa] was the stoutest, and the Fever Tree the most slender. Hymenosporum flavum was the tallest, and Acacia robusta the shortest.

The front of the garden had been terraced so that there was an exceptional view of the Umgusa River, about a hundred yards distant, and around a hundred feet below. On the edge of the terrace grew a truly gigantic Tipuana tipu. Almost as big was an Acacia erioloba, perhaps over 150 years old, on the other side. This tree, for some obscure reason, had been the victim of lightning strikes, and now a conductor had been erected within its branches to protect it.

We set off down through the lands, and our first stop was by a large group of Acacia karroo. These trees were probably a good example of what is known as episodic regeneration. They were very tall and large in girth.

Our next stop yielded a treasure – Acacia mellifera. Then we went round, through and among some huge Acacia galpinii, on an extraordinarily bad road, which brought us to what was known as the sunken land. For me, this was a highlight. It is an extensive depressed area, where maize is being cultivated.

On the far side, opposite where we were driving was a cliff of alluvial red soil. We learnt that Southern Carmine Bee-eaters nested here. This amazing land had been created some time in the geological past by the Umgusa River, which gouged out gullies. The soil had collapsed, creating a sink-hole, and eventually the alluvium was carried away, leaving a level plain surrounded by the aforesaid cliffs.

An unusual feature of the farm was the avenue planted with mulberries, a distinctly different and pleasant experience.

We thank the Randells for allowing us to look at their most interesting farm, and we thank Jonathan for sharing his knowledge with us.

–NORMA HUGHES

IN RETROSPECT

From TREE LIFE No. 3 (June 1980): Good news is that the lease with the Municipality is ready for signature, and members should look for details in the national press. An open day will be held by the MWA (Mukuvisi Woodlands Association) on Sunday 29th June 1980 and, again, details will be given in the press. In view of continual Tree Society involvement with this very worthwhile project over a long period of years, we hope that there will be a good turnout of our members at this open day.

Members will recall that the Tree Society committed a sum of $250 from our reserves as our contribution to the woodlands project. Once the lease has been signed we will pay this amount over to the M.W.A., together with what else we are able to collect from our membership, and in terms of our resolution in 1978, we hope to raise a further $250, and therefore make a total contribution of $500.

Again, I would like to remind our members that this financial contribution to the woodlands project is, in fact, our society’s memorial to the late Douglas Aylen, who worked so hard to preserve the woodlands, and who, I am emphatic to say, was very largely responsible for the ground work in years past, which has led today to the Makabusi Woodlands Association. In saying this I do not wish to belittle the sterling efforts of all others who worked in harness with Douglas, but Douglas was our man, and this contribution by our society will be our memorial to Douglas. And this will, in fact, make the whole of the woodlands project a living memorial to our collective fond memories of Douglas, and the great man he was.

[Comment 2000: The Makabusi Woodlands is now known as the Mukuvisi Woodlands, Mukuvisi being the original Shona name of the river that we used to know as the Makabusi].

TEMNOCALYX OBOVATUS, A BUSH TEA (Makoni Tea Bush)

A note by George Hall, TREE LIFE No. 4 (July 1980):

This plant was first pointed out to me by a tribal person a number of years ago as a ‘test bush’. Later I collected some leaves and took them home and dried them in the oven. When they were crisp I brewed a cup of tea that was quite pleasant to taste; however; few hours later I developed a headache, a mild one but enough for me to connect it with the ‘cup of tea’. A few days later I met that same person in the street and told him of my headache. He pointed out that I had been wrong in artificially drying the leaves; I should have waited until they dried naturally.

The next time I experimented I made sure that I did just this, and the result was no side effects. When the leaves dry out naturally, reduce them to fragments, pour on boiling water, stir until the leaves have sunk, and drink immediately. I find that if the tea begins to cool a certain bitter taste develops, but some might in fact develop a liking for this. Like China tea, no milk or sugar. I would be interested to hear the comments of professional tea tasters on the world markets.

I hope it never becomes too popular because Temnocalyx obovatus [Fadogia ancylantha] is not very common.

[Comment 2000: The Rhodesian Botanical Dictionary of African and English Plant Names (1972) describes Temnocalyx obovatus (Rubiaceae) as a shrub to about 1 m, branching from the base; leaves opposite, sessile, more or less rhombic, widest well above the middle, about 50 x 35 mm. Apex with short, blunt drawn-out point, base wide wedge-shaped; flowers cylindrical, about 25 mm long, greenish, sometimes slightly curved, borne single or a few together on slender axillary peduncles. Fruit a black, fleshy berry, about 5 mm diam.Widespread. Locally common in open woodland. Leaves infused for tea in the Makoni and adjacent districts. Shona names mukandandamirapamhiri, mumbudzimbudzi.

DJ Mabberley’s The Plant Book (1993) has Temnocalyx as a monotypic genus from Tanzania.]

ECOLOGICAL COLLAPSES IN HISTORY

A contribution by G.H. in TREE LIFE No. 5 (August 1980):

The recent news report about drought in Zululand reminds us how much of a ‘knife edge’ is the boundary between ecological balance and collapse. Zululand, a well-watered country, has perhaps been on this knife edge for up to 10 generations because of over-population (the term is relative, not to be measured in terms of bods per acre alone), and it now faces the prospect of collapse from a succession of drought years.

Coming closer to home, I note that expert opinion is not shy to ascribe ‘ecological collapse’ as being the cause of the abandonment of the civilization that formerly existed in Great Zimbabwe Ruins just when the social order that ruled there was seemingly in its prime. A warning to us all, and coming right on to our own doorstep, is this perhaps the place to ask if a little of the many millions of foreign aid that is being promised to this country could, perhaps, be spent on rehabilitation of the near ‘moonscape’ conditions on the ground around Chitungwiza new town. It would be a fascinating project, one that would provide a lot of much-needed employment, and which is, I think, vital not only to prevent ecological collapse in a vital part of the catchment area, but also to prevent moral and social decay amongst the communities in the vicinity.

All these thoughts were prompted by my reading of the following report, which I transcribe in slightly simplified form:

“Above the City we laid out a park, the wealth of the mountains and the lands, herbs and fruit-bearing trees, we set down for our people to see. In past generations the river had been low, and some years had stopped flowing, but we built a dam to control and feed the waters to the cultivated lands. Where there were springs we built reservoirs and cut canals through difficult places to irrigate a thousand fields below the City, and the orchards, in the hot season. To control the flow of these waters we made a swamp and set out a cane brake within it. lguri birds, wild swine, beasts of the forest we turned loose therein. By command of the god, within the orchards more than in their native habitat, the vine, every fruiting tree, and herbs throve there luxuriously – the mulberry, the cypress, the reeds of the brakes that were in the swamp and the wool-bearing trees we sheared and wove the wool into garments”.

We do not know what the iguri birds were, but the ‘wool-bearing trees’ were obviously cotton. The foregoing is an extract from the record of the reign of King Sennacherib (705-681 BC) in the annals of Assyria, and the city referred to was Nineveh. What better description could be found of a ‘relationship harmonious between nature and man’ as was propounded by our late colleague Wilhelm Gilges.

It is, I know, fruitless to speculate on the ‘ifs’ of history, but how different may have been the subsequent story in the Middle East had the excellent ecological work of Sennacherib been continued uninterrupted. As it was, in the times of his grandson, the empire collapsed and the destruction of the fabric of the state ensured that the irrigation system stopped working. Some agricultural life continued along the line of hills, but the river-valley life was reduced to a low level not known since prehistoric times. Assyria became a backward country, and virtually disappeared from history. Only by chance does history again, in olden times, mention this place, which must have been so delightful in the 7th century BC. Xenephon and his ten thousand passed along the Tigris, and commented on the poverty of the small peasant groups along the river. Alexander the Great fought Darius there, and, as an aside to the main item on the agenda, only visited the ruins. There was nothing else for the tourist to see.

[Comment 2000: There is well-documented evidence that the collapse of one of the great centres of the Mayan civilization in Guatemala, at the end of the 10th century AD, was due to over-population and the depletion of the natural resources. This was repeated almost precisely by the Great Zimbabwe civilization some 500 years later.]-LYN MULLIN In Retrospect – To be continued.

A CAUTIONARY NOTE

Euphorbia cooperi. Photo: Mark Hyde. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

n 1983 (when I knew nothing about trees) we built our own house and decided that a candelabra tree would look nice in our new garden. I chose a Euphorbia cooperi. As they are so prickly I slashed a piece off with a big knife. It fell on my left foot, punctured the second toe and a lot of ‘milk’ was splashed onto the area. I rinsed it under a tap and thought no more about it until evening. As the night progressed so did the pain – it was the worst pain I have ever experienced (including childbirth!!). The next day my husband carried me into the Doctor’s surgery. He dressed it with some sort of poultice and we picked up some crutches. After a couple of days, huge black blisters developed and the little sore also turned black. The Dr. changed the dressing to an antibiotic one and gave me an antibiotic. After about a week it started smelling. One look at it and my Dr. was on the phone to a plastic surgeon in Harare. I rushed up there on the same day and was operated on the next day, and had another operation a few days later. A large area had to be ‘gouged out’ and as the tendon on my toe had almost been eaten through it had to be cleaned up and rejoined.

The plastic surgeon did a great job making it all look beautiful again. Three weeks later I started walking on my foot, still with the aid of crutches. The candelabra was thrown far away.

Jenny Holman, Mapor Estates Odzi.

THE INDABA TREE AT THE PIONEER NURSES MEMORIAL

The encampment was perched on the top of a steep, rocky hill, and in the space in front of the huts an enormous tree of the fig species spread forth its branches. This was the only large tree in the whole district, and Sabi Ophir Hill was known to the natives as “the hill of the great tree”.

R. BLENNERHASSETT & L. SLEEMAN (1893) – ADVENTURES IN MASHONALAND

Ficus lutea . Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

As you approach Penhalonga from Mutare a sign will direct you to the Pioneer Nurses Memorial, a little less than a kilometre away along a winding road. The memorial is one Zimbabwe’s national monuments, and was created as a tribute to the country’s pioneer nurses – Rose Blennerhassett, Lucy Sleeman, and Beryl Welby. These young ladies, the first trained and qualified nurses to enter Zimbabwe, had been recruited by Bishop Knight-Bruce in April 1891 to establish a mission hospital in Mashonaland, a territory that only 8 months earlier had been occupied by Cecil John Rhodes’s Chartered Company.

They travelled by boat from Cape Town up the east coast of southern Africa to Mpanda’s on the Pungwe River, and from there they set out on 1 July 1891 on their historic 225-km walk to Penhalonga, which they reached on 14 July.

The nurses were accommodated in huts belonging to the Sabi Ophir Mining Company, and there they lived until the end of their appointment in 1893. The fig tree in front of the huts was an indaba tree, where the local chief of the area held court, and it was beneath this tree that the Nurses Memorial Garden was created in 1941 to mark the 50th anniversary of their arrival in this country. It was a specimen of the Giant-leaved Fig, Ficus lutea (formerly Ficus vogelii), but, sadly, the old fig has gone. Struck by lightning, then set on fire by honey hunters, it had to be removed.

But young trees were propagated from it by cuttings and truncheons, and three of them were planted at the Memorial Garden. The largest of these was measured in October 1985, when it had a diameter of 1.39 metres and a crown spread of about 30 metres.

-Lyn Mullin

THE BURNING QUESTION

A recent issue of a quarterly newsletter, Forestry for a Small Planet, Issue No. 37, Summer 1999, contains an interesting note on the fuel-wood crisis in South Africa.

‘Research indicates that by the year 2000 South Africa will face a deficit of four million tonnes of fuel-wood at the current rate of consumption.’ The note then goes on to look briefly at the reasons for the deficit, and the reasons for the failure of measures to address it. But the interesting thing, to me at any rate, is the magnitude of what will have to be done to provide enough fuel-wood for those who need it.

Those who travel regularly to South Africa by road will be well aware that it is a country largely devoid of extensive areas of woodland or forest, especially where the vast majority of the people reside. This means that the only way to provide the huge requirements of fuel-wood for them is to grow it in plantations, and the only realistic trees to grow would be eucalypts. It does not need a mathematical genius to calculate what area of plantation would be required to provide for the indicated deficit of fuel-wood, but one would have to have some perception of the quality of land that might be available for such plantations. All the most productive land is already taken up and I doubt whether one could expect anything better than a sustainable mean annual increment of 8 cubic metres of fuel-wood per hectare per annum from the land that might be available.

Rotation ages (cutting cycles) for fuel-wood plantations could not realistically be longer than 5 years, so the mean annual increment might even be less than 8 cubic metres per hectare. Four million tonnes of fuel-wood would equate to a volume of between 4 million and 6 million cubic metres, depending on species. And this would require a plantation area of between 500 000 and 750 000 hectares to produce it, on a sustainable basis, in scattered large or small blocks around the country. What hope is there of South Africa ever committing that much land to fuel-wood? And what is the economically realistic alternative? That must be the burning question.

-Lyn Mullin

A SHANGAAN AND HIS TREES

From HARTEBEEST No. 6 1974

Julias Manavele, son of Manavele, is a Shangaan of the lowveld and was born about fifty-five years ago on the banks of the Makari River on Triangle, where he is now attendant in charge of the High Syringa Game Park.

His father worked for the lowveld pioneer, Murray MacDougall, and it was perhaps natural that Julias, in his turn, should enter service on this sugar estate. Starting as a herd boy, graduating to milkman, and then organising the trek oxen which hauled logs of Pod Mahogany and Knob-thorn to MacDougall’s pit saw.

He was unhappy when he was ‘promoted’ to look after the steam boiler that provided power for the pit saw, maize mill and water pump, and when he ran away, his father sternly retrieved him and put him to work in the cane fields. When again transferred to steam engine maintenance, he ran away to seek his fortune in South Africa, returning after some years to work on Nuanetsi Ranch as a cattle boss-boy. Here he was happy for years, enjoying the open air, caring for various wild animal pets and orphans over the years, and quite content to live in the lowveld bush.

When Triangle Limited decided to set up a Game Park under the direction of a former employee of Nuanetsi Ranch in 1965, Julias presented himself and asked for a job, and was duly installed as Game Park Attendant.

He had been a vegetarian for many years and his very genuine love of the lowveld’s wild life made him ideally suited to the post. When, in 1966, I took over direction of the Park, I quickly found out that Julias Manavele was a superb natural amateur botanist. Having been taught by his father and his elder brother of the wealth of resources available to a knowledgeable human being from the trees and shrubs of this environment. It is a source of profound regret to Julias that his children are not appreciative of the tremendous value of this knowledge, and over the past few years, I have recorded certain information concerning the uses to which a wise Shangaan puts his trees. No particular classification or order of presentation is attempted and I have merely presented the information as I have recorded it in several fascinating sessions, starting with the dominant and prominent trees of the lowveld scene.

Adansonia digitata: Baobab: Muwu

Bark used for manufacture of string for game and fish nets, snares for game and birds, and for binding reed mats. Seeds ground up with milk or water to make porridge. Leaves and flowers not eaten. Hollow baobabs a source of honey, water and shelter. Pods are burnt and crushed, then mixed with tobacco and smoked.

Colophospermum mopane: Mopani: Shanatsi

From scrub mopane is made a fibre for binding poles together in hut construction. Poles are extensively used in huts as main construction material. Mopane fibre also used in binding reed traps for catching fish. Mopane caterpillars (matamani) a favoured relish.

Afzelia quanzensis: Pod Mahogany: Shene

Planks are cut for manufacture of doors, and for huts, if a villager has any carpentry expertise. Drums (ngoma) are made from hollow trunks. Pods are burnt and crushed for mixing with tobacco. The seeds are used as playthings for children.

Sclerocarya birrea: Maruni: Nkanyi

Bark peeled off the trunk makes canoes or beehives (Ntoko). Trunks used as pestles and as mortars for grinding grain. The trunk is also sometimes used for making drums. Spoons are made from the wood. Fruit is eaten raw and also after fermenting; after skinning, water is added and the mixture put into a pot. Women and children drink the concoction after one day, men leave it for three days, when it is more potent, and it is then drunk after removing the scum from the top. Nuts (timongo) are eaten raw. Skins of fruits are dried in the sun and then may be burnt and added to tobacco. Other skins are put in a sack after burning, water is added and the mixture is strained – water dripping out of the sack is boiled until it evaporates away and leaves a type of salt (mahlawa) which is also added to tobacco.

Kirkia acuminata: White Syringa: Umvumaile

Large forks are used in the manufacture of sleighs for carrying water and grain. Planks are cut with an axe and used for making hut doors.

Diospyros mespiliformis: Ebony: Toma

Yokes and skels for cattle are made from the wood, which is also extensively used for manufacture of axe handles. The fruits are eaten.

Ficus abutilifolia: Rock Fig: Chikuwakuwani.

The fruits are eaten as a delicacy.

Grewia bicolor: Donkey Berry: Sihani

A prized material for manufacture of both bows (ware) and arrows (sewe). The fruits are eaten.

Grewia flavescens no common name Palambati

Branches are used in making huts, between larger stronger poles. Fruits are eaten.

Colin Saunders

This fascinating list continues in the next issue of Tree Life.

PLEASE collect seeds for two members. Ann Bianchi needs seeds of any indigenous species & Anthon Ellert needs seeds of any of the Commiphora species. Pack the seeds into separate paper packets remembering to label them with the species name, date, and location where collected.

If they are left with any committee member, the packets will be forwarded to Ann or Anthon.

ANDY MACNAUGHTAN CHAIRMAN