TREE LIFE

January 1985

MASHONALAND CALENDAR

Tuesday January 8th : Botanic Garden walk. Meet in the car park at 1645 for 1700 hours. NB postponed for one week to avoid clashing with Hogmany hangovers!

Sunday January 20th : Kugeri Farm, Arcturus, the home of John Curtis. What with the Christmas rush, entertaining etc. I confess that we have not actually been able to do a recce but from the sounds of it a good variety of mixed woodland can be expected, and by then we shall have done a reccee to spy out the interesting areas. Bus booked, Fare $7.00. Bus will leave Monomatapa Car Park at 0900 hours.

.

SUNDAY 17TH MARCH 1985 : ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

Notice is hereby given that the 35th Annual General Meeting of The Tree Society of Zimbabwe will be held on Sunday, 17th March, 1985 at 12 noon at Danbury Park Farm, Old Mazowe Road.

AGENDA

- Notice convening the meeting

- Minutes of the last AGM, to be circulated in forthcoming Tree Life

- Matters arising from the Minutes

- Chairman’s Report

- Treasurer’s Report

- Election of Officers

- Any Other Business.

Any proposals/resolutions and nominations for Office Bearers should be sent well in advance to P.O. Box 2128, Harare.

As mentioned before your present Chairman, Vice Chairman and Treasurer will be standing down from those positions and will not be seeking re-election. For the past year we have not had a Secretary as such. So we earnestly seek nominations (or at least discreet suggestions) for persons to serve on the Committee generally and in those positions in particular and ask that written nominations be received by the Chairman. This will not prevent nominations from the floor at the meeting.

MATABELELAND CALENDAR

Sunday January 6th 1985 : Meet at 0830 hours at the Blake’s House, 5 Ngezi Avenue, Glenville. From Town take the Falls Road, turn into Glenville Drive, opposite the Racecourse Shall sign, and after crossing the little Bride at the top of the rise turn right into Sturton Drive East, and follow this to Ngesi Avenue, close by.

BOTANIC GARDEN WALK 4TH DECEMBER 1984

Despite the dark cloud cover and odd shower along the way, both Tom Muller and Bob Drummond led the walk as we looked at the Albizia genus. These trees belong to the family MIMOSACEAE. This family may be distinguished from the other two legume families as the leaves are generally bipinnately compound with an even number of both pinnae and leaflets. Within the MIMOSACEAE, Albizia may be distinguished from Acacia as Albizia usually lack thorns. For the occasion where branches are all too far away, such as at one memorable Chegutu trip, then the fallen seeds of Acacia are usually adorned with a horse shoe pattern on the side whereas in Albizia the seed is often fairly uniform in colour with a small mark on the one side which heightens the illusion of a tick.

We began by examining A. zimmermannii, a tree we may remember from the schist and limestone slopes around Dichwe where the striated bark resembles that of a young seringa, Melia azedarach. In Dichwe Lemon Forest itself, these trees grow to a magnificent height and girth such that even binoculars fail to detect the leaf form. In the north of Zimbabwe this species seems to replace B. glaucescens on the slopes. The main vein of each leaflet is distinctly central. The only other Albizia with which it may be confused is thus A. schimperana. The latter is a pioneer of the drier rain forests of the east. These two trees may be distinguished on distribution alone.

Albizia gummifera. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

In the Eastern Mountains A. schimperana is sometimes confused with Albizia gummifera and A. adianthifolia although the leaflet of both the latter species has a diagonal vein. A. gummifera has rectangular shiny dark green leaflets and usually grows in wetter forests than A. schimperana. On the slopes around Vumba where both species exist together the red stamens of A. gummifera separate it from the cream white heads of A. schimperana. In most Albizia species the base of the pinnae is swollen to form what is termed a pulvinus. This structure may or may not function in changing the angle of the pinnae in response to light or moisture. A. schimperana and A. adianthifolia the pulvinus is adorned with two stipels or stipelules, these are absent in A. gummifera. The square leaflet of A. adianthifolia is attached by one of its corners whereas in A. gummifera the attachment point is off the corner resulting in a short ‘heel’ on the one side. In contrast to the smooth forest bark of both A. gummifera and A. schimperana, A. adianthifolia has a rough fire adapted bark and may be found growing in more open forest. Just to confuse botanists, in the Haroni Valley forest the bark is smooth like other forest species. In the Honde Valley where this is a lower altitude pioneer there may be a change in the colour of the canopy where this species becomes common. The leaflets are much more hairy than A. gummifera and therefore not as shiny. The gland on the petiole is larger than in the other species and proves to be a great attractant for little ants who gather around these glands. By means of this attractant the tree may gain protection, as the ants disturb caterpillars or even actively attack small herbivores. A. adianthifolia may have a flat top and may not grow as tall as the other species, Tom has measured a fallen A. schimperana of 58 m, this huge specimen destroyed much of the surrounding forest in which it had been growing. Unlike most Albizia flowers where the stamens all stick out like a shaving brush, three indigenous species have a tube formed from the fused stamens; these include A. gummifera, A. schimperana, discussed above, and thirdly A. petersiana var. evansii of the south east lowveld. This was the only species which we found in flower. This bears a remarkable resemblance to those of A. gummifera with spiral red stamina tube and central white floret, A. petersiana tends to have few square leaflets, these may help to distinguish it from the lowveld A. anthelmintica, the latter has prominent lenticels on the bark in addition the short side branches may end as sharp spikes as occurs in Dichrostachys.

There are four Albizia species with fine leaflets, two of which, A. harveyii and A. amara are often confused, particularly where they grow together. Technically A. harveyi has a sickle shaped leaflet not found on A. amara. Brian Best has found that sometime the leaflets are indistinguishable when mounted flat, although on the plant those of A. harveyi may appear to be more curved. Tom suggests that the position of the gland on the petiole may help in identification of some Albizias, and in the Gardens at least the gland of A. harveyi always appears to be on the top half of the petiole, whereas in A. amara it is on the lower half, this needs to be tested in the field. Another significant difference is that in A. harveyi the leaf scar often hardens to form a sharp spine which may not be seen, but may be found by finding a short side shoot and then feeling the main branch immediately below it in the position of the leaf scar. A. harveyi grows in the lowveld along rivers and woodland. Around Harare it may be found in sodic soils. The third indigenous Albizia with fine leaves is A. brevifolia, unlike the two above it forms a multi stemmed bush. A. forbesii also has small leaflets but has few pinnae, 2 – 7, each with fewer leaflets than the other fine leaved species. This is yet another species from the cretaceous sandstones of the south east lowveld. A. versicolor has fairly large furry leaflets the golden hairs on the rachis and pinnae give the tree a golden appearance. This medium to low altitude tree has received notoriety as cattle which eat unripe pods dislodged by high winds around August die a rapid and painful death. As a result many farmers have selectively removed this tree from grazing lands. A. glaberrima also has large furry leaves, although the last two resemble the footprint of a duiker. These slender trees grow in the eastern lowveld riverine areas and the Horoni Valley. A. glaberrima may be confused with A. antunesiana although the latter is more bicoloured. We generally see A. antunesiana as an undergrowth of purple flush.

The last indigenous species A. tanganyicensis we did not see on the walk, although it has made an appearance on a number of our outings lately. The smooth peeling bark is unmistakable

We must thank both Tom and Bob once again for a rewarding walk, and trust they have enjoyable trips to Europe.

-Kim ST.J. Damstra

MATABELELAND NOTES

Sunday December 2nd : We went to the Junction of the Circular Drive and the Old Gwanda Road. This time, weather permitted, but only just. We were most fortunate in having Meg Cates Palgrave to guide our erring steps and to sort out some of our problems. There was a pleasing variety of Trees in the area. Among them Acacia karroo, A. nilotica, Albizia antunesiana, Azanza garckeana, Berchemia zeyheri, Bridelia mollis, Burkea africana, Canthium lactescens, in heavy flower, Carissa edulis also flowering Cassine matabelica, Clerodendrum glabrum, C. myricoides, both of which left many fingers stinking Combretum apiculatum in tender new leaf, Commiphora schimperi, of which several were fruiting, showing their difference from Commiphora africana, which they resemble closely. The fruit has a pointed, almost spiked apex. Other differences are the shiny green near hairless leaves, and the relatively smaller size of the terminal leaflets, only about double the laterals. Also the petioles are shorter, and the leaves, whilst trifoliate, are clustered.

Dichrostachys cinerea. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

Also, Dichrostachys cinerea, Diospyros lycioides, both in flower, Dombeya rotundifolia, leaves rather small perhaps due to the drought, Ehretia rigida, with fruit still greenish, Euclea divinorum, Euphorbia ingens, Ficus thonningii, here Meg sorted out our considerable confusion on Figs, and promised further help, Flacourtia indica, Gardenia spatulifolia, Grewia flavescens, Grewia monticola and what was probably G. decemovulata, Lannea discolor, Maytenus senegalensis Pappea capensis, Pavetta gardeniifolia and P. schumanniana, both flowering, Peltophorum africanum, just starting to flower, Pseudolachnostylis maprouneifolia, flowering, Rhus pyroides, Rhus tenuinervis, Sclerocarya birrea, Securinega virosa, Strychnos cocculoides, Strychnos spinosa, Terminalia sericea and Terminalia trichopoda, we are still a bit confused over these, Turraea nilotica, Vangueria randii, fortunately pointed out by Meg, as otherwise we might have thought it was V. infausta, Ximenia caffra and Ziziphus mucronata.

After an instructive morning we took our tea to the delightful garden of Ken and Thora Hartley nearby. We sat under a fine Ficus sur, and apart from the magnificent roses we saw various indigenous trees, including a Halleria lucida.

Further to the Terminalia problem, I looked back at my notes on the Terminalia species differences at the time when we studied this genus in the Botanic Gardens. I was obviously much more concerned about the differences between. T. trichopoda and T. stenostachya and so on the Bulawayo outing was still somewhat confused about T. sericea/T. trichopoda differences. From the books I gather that the differences could be as follows :

Terminalia sericea Terminalia trichopoda

Fruit up to 3.5 cm long Fruit more than 3.5 cm, up to 7.5 cm

Hairs – silvery Hairs maybe silky not silvery

Leaves up to 12 cm Leaves about 13-15 cm

Petioles up to 10mm Petioles up to 20 mm

Secondary veins not raised on the under surface Secondary veins conspicuously raised on the

under surface freely and presume all five points

It would be well worthwhile trying this key bearing in mind that these two species hybridize freely and presume all five points would have to be right for there to be a true species.

I shall be in Bulawayo at Christmas and propose to have a look for myself as well.

-Meg Coates Palgrave

CHEGUTU NOTES – OUTING TO CHIKANGA FARM, GADZEMA, SUNDAY 2ND DECEMBER

Travelling down to Chegutu at this time of the year, with every roadside puddle over hung with the large meringues of tree frog nests reminds me of my research work and all the associated nightmares of a thesis. Nevertheless Chegutu is always a rewarding spot for relaxed botanizing, this time along a magnificent riverine frontage where the Biri river runs over spotted rocks and falls down enormous granite boulders. Our hosts, Mr. and Mrs. Terry Fynn provided a warm welcome at their farm. It really is rewarding to be surrounded by the happy band of Chegutu enthusiasts once again. After tea we travelled to the river through mixed Julbernardia/Brachystegia boehmii and B. glaucescens woodland, passing a Catunaregam thicket and a large Bauhinia petersiana in full flower. The day was so crowded with fresh impressions that I will gloss over all but the highlights. Fine specimens of Pteleopsis anisoptera grew alongside the river. The ripening fruit resembles that of the Combretum with four wings but the wings continue along the stalk. Clutching the bare rocks was Ficus abutilifolia with deep red veins sprawling across the leaf life a fresh arterial dissection. Vangueriopsis lanciflora caused its usual problems. This specimen though had the very lop sided fruit. We found both Margaritaria discoidea and Erythroxylum emarginatum and were able to see the ‘lizard legs’ twigs and crackling cuticle on the leaf of the latter. These two plants are easily confused. We all sat guessing alongside a slender tree which overhung the river bank. The shiny green leaves gave the impression of being succulent and were folded in such a manner to make pressing of them flat and open almost impossible. It also hung with small ripening orange fruit. After some thinking we worked out it must be Olax dissitiflora although the twigs were not as 4 winged as they could have been. This was confirmed by Steven Mavi at the Herbarium.

Hexalobus monopetalus. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe

It was a day for ANNONACEAE and their look alikes. The Hexalobus monopetalus appeared to be covered in uncharacteristic large oval fruits until we realized that these were strange galls. Artabotrys brachypetalus had us confused until we noticed the grappling hook, being the remains of the flower stalk. The leaves of Friesodielsia obovata were coming out with that typical ANNONACEAE bud development. Also along the riverside was Antidesma venosum, this is one of those EUPHORBACEAE which may resemble an ANNONACEAE although the young twigs clearly showed the stipules which distinguish these two families. Other riverine treats were Mimusops zeyheri in flower, Diospyros natalensis, Maytenus undata, Euphorbia matabelensis, Flacourtia indica in flower and Garcinia buchananii. We headed away from the river and wondered into a tall Brachystegia boehmii/Julbernardia woodland. Here we found the dwarf Ochna macrocalyx with the large yellow Ochna flower sticking out of the ground.

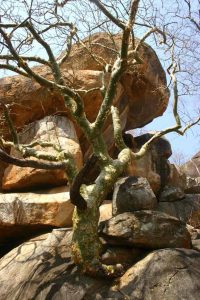

With the usual Chegutu heat we retreated to a grove of Dalbergia nitidula for lunch. Some of these trees had galls which resembled sea urchins, apparently characteristic for this species. With the sun sapping our remaining energy we headed over the Biri River. Amongst the large boulders we found large specimens of Zanha africana laden with the orange fruit which appears almost translucent in the sunshine. The peeling barks of both Albizia tanganyicensis and Commiphora marlothii never ceases to appeal. Large specimens of Kirkia were in full flower. A hum of bees surround these blooms, the 4 stamens of the male flower form an arch above a thickened structure which may produce the nectar they seek. As we wilted in the heat we passed a fat female tree frog sitting happily in the sunshine on a branch not far from a recently constructed foam nest. These frogs seem to defy both the sweltering heat and my research.

Commiphora marlothii. Photo: Bart Wursten. Source: Flora of Zimbabwe.

On the return journey to the farmhouse we stopped to see some rock paintings alongside a Commiphora marlothii, Ann Bianchi found a twig which fooled us all. At the herbarium Steven Mavi went straight to the specimens of Diospyros squarrosa, we should have noted the large persistent calyx around the developing fruit, a usual feature in Diospyros. The leaves are distinctly obovate. This is yet another of the Zambezi Valley plants which extends its distribution up river valleys to Chegutu.

I am afraid my northern temperate ancestors lacked the genes to cope with the tropical temperatures and so I welcomed the cold water and volumes of tea back at the farm house. We headed back to Harare via the Gadzema – Selous road through Capparis country such a different atmosphere to the high veld. We really must thank our hosts, the Fynns, for their hospitality, Ann for preparing the trip and doing the recce and the Chegutu folk who we were pleased to meet once again.

-Kim ST.J. Damstra

FOOT NOTE : There has still been response to the request for ideas on why some of our indigenous trees which grow on rocky outcrops have a peeling bark. Here are some ideas to get you thinking : It is obviously not because they are related, as different families are represented; these include MIMOSACEAE (Albizia tanganyicensis) STERCULIACEAE (Sterculia quinqueloba and S. africana) and BURSERACEAE (Commiphora marlothii and, to a lesser degree C. africana). The following thoughts occur : 1. LACK OF FIRE – a thick corky bark, e.g. Strychnos cocculoides, Parinari and Erythrina abyssinica is usually associated with an area exposed to fire. One commonly sees these corky barks black and charred, fires seldom penetrate the granite boulders where the peeling bark community lives. There is so little undergrowth here that there is no fuel to support a burn. We would not expect a thick bark on a tree which is protected from fire. This also applies to forest trees. With a thin bark the trunk may contain chlorophyll and thus produce food. This chlorophyll results in the green trunk of the peeling Commiphora species. These trees can thus produce food even when they are leafless. The advantage in producing food in the trunk, in contrast to being evergreen and keeping leaves during the dry season, is that leaves have stomata which may lose much water. The trunk loses less water although it breathes through spaces known as lenticels. Not all of the peeling bark trees make use of their thin bark in this way. 2. HIGH TEMPERATURES : These rocky kopjes are also exposed to high temperatures, and is this flaking not the closest a tree can come to loose, well ventilated clothing? These peels may shade the tree and encourage eddies of wind around the trunk. It is noteworthy that the granite boulders which exist where these trees grow, e.g. Matopos, may also be characterized by peeling in flakes. The alternate heating and cooling of the boulder leads to this condition known geologically as exfoliation. This weathering results in the smooth round shape so characteristic of Zimbabwe. The Oxford dictionary states “EXFOLIATE – of bone, skin, mineral, etc. come off in scales or layers; of tree throw of layers of bark.” This remarkable similarity between vegetable and mineral cannot reflect a common cause, as the peeling bark species will exfoliate even when planted in the Botanic Gardens whereas a pet rock from the Matopos will not be expected to moult if kept indoors. The immediate agent causing peeling is thus the bark formation, the long term condition which may tend to favour peeling on kopjes, or the secondary cause is the one we would like to discover. So exfoliation in trees, in contrast to exfoliation in rocks is not caused by high temperatures, although such bark may be favoured in areas of high temperatures.

Maybe now you will get thinking and we can put forward more suggestions later.

-Kim ST.J. Damstra

PHILIP HAXEN CHAIRMAN